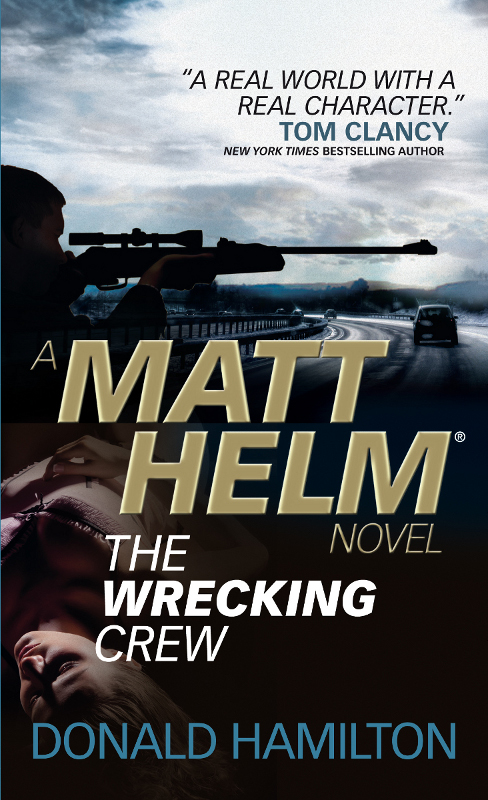

The Wrecking Crew

Authors: Donald Hamilton

Available from

Donald Hamilton

and Titan Books

Death of a Citizen

The Removers

(April 2013)

The Silencers

(June 2013)

Murderers’ Row

(August 2013)

The Ambushers

(October 2013)

The Shadowers

(December 2013)

The Ravagers

(February 2014)

A

MATT HELM NOVEL

THE WRECKING CREW

TITAN

BOOKS

The Wrecking Crew

Print edition ISBN: 9780857683366

E-book edition ISBN: 9781781162316

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First edition: February 2013

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Copyright © 1960, 2013 by Donald Hamilton. All rights reserved.

Matt Helm® is the registered trademark of Integute AB.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Did you enjoy this book?

We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at

[email protected]

or write to us at Reader Feedback at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website:

www.titanbooks.com

Contents

1

I awoke early, shaved, dressed, draped myself with cameras and equipment, and went on deck to record our entry into the port of Gothenburg. I couldn’t think of a likely market for the shots, but I was supposed to be an eager and ambitious free-lance photographer, and I’d be expected to be alert to the chance that somebody would fall overboard or the ship would hit something.

Nothing happened, and after we were safely docked I went down to breakfast, after which I came back up to the smoking room for passport inspection. Finally I was shunted down the gangplank into the arms of the Swedish customs, where I braced myself to justify my possession of a thousand bucks’ worth of photographic gear and several hundred rolls of film, having been warned that European countries are touchy about this sort of thing. It was a bum steer. Nobody paid any attention to the cameras and film. The only part of my belongings that caused a mild official interest was the guns.

I explained that an editor in New York had arranged with a sporting character in Stockholm to have an import permit waiting for me at the dock. I was thereupon escorted down the long shed to an office where a blond young fellow shortly produced a document authorizing Herr Matthew L. Helm, of Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA, to transport into the kingdom of Sweden one

räffla gevär, Winchester, kaliber .30-06,

and one

hagelbössa, Remington, kaliber 12.

The youthful customs man checked the serial numbers of the rifle and shotgun, then laid the weapons on a platform scale, wrote down the total weight in kilograms, consulted a table with this figure, and announced that the duty would be thirteen crowns. Having already learned that the Swedish crown was worth approximately twenty cents, I couldn’t feel that the tariff was exorbitant, but it did seem like a funny way to assess it.

As I left the office, I soothed my conscience with the thought that by not declaring the aluminum-framed, five-shot Smith and Wesson .38 Special concealed in my luggage, I wasn’t really cheating the Swedish government of much money—less than two bits, in fact—since it was a very light little gun.

It had been Mac’s idea. “Your bona-fide literary and photographic background is going to come in very handy on this job,” he’d said, giving me my instructions in his Washington office. “To be perfectly frank, it’s the chief reason you were selected, in spite of the length of time that’s passed since you were associated with us last. There’s also the fact that you already know the language, after a fashion, and we haven’t many operatives who do.”

He’d looked up at me across the desk—a spare, gray-haired man of indeterminate age, with coal-black eyebrows and cold black eyes. Somehow he always managed to arrange his offices, wherever they might be (I could remember one in London with a grim view of bombed-out buildings) so that he had a window behind him, making it hard to read his expression against the light, which I suppose was the idea. “You’ve done articles for outdoor magazines in the past,” he’d said. “What’s more logical than for you to be working on a couple of hunting pieces in addition to your main photographic assignment? I’ll get in touch with some people and fix it up for you.”

I said, “There’s going to be a lot of red tape with the guns. Other countries are more sensitive about firearms than we are.”

“Precisely,” he said. “That’s just the point. You take a lot of trouble to get the proper papers for your hunting arms, all open and innocent, and who’s going to suspect you of packing a revolver and a knife as well? Anyway, they’ve got some pretty wild terrain up there in northern Sweden where you’re going. Who knows, a high-powered rifle may be just what you’ll need.”

It had still seemed like an unnecessary complication to me. I hadn’t looked forward to juggling a rifle and a shotgun, plus a lot of hunting paraphernalia, in addition to the camera junk I was already saddled with by my role as photographer. However, as Mac had pointed out, I’d been out of touch for a long time; I wasn’t familiar with the subtleties of peacetime operation. But I did remember clearly from the war that there were limits to the amount of argument Mac would tolerate from a subordinate, particularly when he felt he was being extremely clever.

“Okay,” I said hastily. “You’re the boss, sir.”

I hadn’t wanted him to change his mind about putting me back to work. And now I was landing on European soil again, after better than fifteen years, with the same old feeling that everybody was looking at me and my belongings with knowing, X-ray eyes.

There was bright sunshine outside the customs shed— well, as bright as you get in the fall that far north. It would probably have seemed like a pale and wintry day, back home in New Mexico. There was a wide, cobble-stoned street outside, full of weird, left-handed traffic. The Swedes, along with the British, persist in driving on the opposite side of the street from practically everybody else in the world.

There were two-and four-wheeled vehicles in just about equal numbers, with some oddly shaped three-wheelers thrown in for good measure. The taxi that took me to the railroad station was a German Mercedes. The train itself had an old-fashioned, unstreamlined look that was kind of refreshing. I disposed of my heavier baggage with the proper official, and started to get into one of the cars, but stepped back to let a woman board first.

She was quite a handsome young woman—from where I stand, thirty still qualifies as young—and she was wearing a severely tailored blue suit that did justice to her figure in a nice, understated way; but her hair, under the little blue tweed hat that matched her suit, was also blue, which seemed odd to me. Of course there was really no reason why a good-looking female of youthful appearance whose hair had turned white prematurely shouldn’t dye the stuff blue if she wanted to.

I followed her aboard. She apparently knew her way around Swedish rolling stock better than I did. I lost track of her in the unfamiliar surroundings. It had been a long time since I’d last patronized a European railroad. This car was divided into small eight-passenger compartments marked either

Rökare

or

Icke Rökare.

Remembering from my Minnesota boyhood that

röka

means smoke in Swedish, and

icke

means no, I had no trouble understanding the distinction, particularly since other signs gave the translation in German, French, and English.

I selected an empty nonsmoker and settled down by the window, which could be raised and lowered by means of a leather strap about four inches wide. I couldn’t recall the last time I’d been on a train that wasn’t sealed up tight for air conditioning, but of course they wouldn’t need that here, in the shadow of the Arctic Circle. It was a long ride to Stockholm, through green, partly forested country interrupted by a multitude of lakes and streams, and accented with red barns and orange-red tile roofs.

Around three in the afternoon, a little late, having traversed the entire width of the country from west to east, the train entered the capital of Sweden across a long bridge over water; but it was twenty minutes more before I could extract my junk from the baggage room and transfer it to a waiting taxi. I’d got over my first feeling of stage fright. Nobody seemed to be paying the slightest attention to me now, except for some kids intrigued by my big Western hat. One of them came over and bobbed his blond head politely. “Yes,” I said, “what is it?”

“Är farbror en cowboy

?” he asked.

In addition to having had some contact with the language as a boy, I’d been given a quick refresher course—not only in the language, but in other subjects as well—before being sent out. But of course I wasn’t supposed to understand a word, and somebody might be watching, so I looked blank.

“Sorry, I don’t read you,” I said. “Can’t you put it into English?”

A woman’s voice said, behind me, “He wants to know if you’re a cowboy.”

I looked around, and there she was again, blue suit, blue hair, and all. Bumping into her a second time didn’t please me a bit. It wasn’t a contact, because there was nobody here I was scheduled to meet in this manner; and I’d once survived a war mainly by putting no faith whatever in the power of coincidence. It still seemed like a sound principle to follow.

“Thank you, ma’am,” I said. “Please tell the kid that I’m sorry, but I never roped a steer in my life. The hat and the boots are just for show.”

This was another of Mac’s fancy ideas. I was supposed to be something of a rustic Gary Cooper character, as well as a hunter and a camera-clicking screwball. Well, I had the height for it, if no other qualifications; but I couldn’t help feeling, with this woman’s eyes upon me, that the act I was being asked to put on was unnecessarily detailed and complicated, not to mention corny. However, I’d asked for the job—after first turning it down twice—so I wasn’t in a position to complain.

The woman laughed, and turned to speak to the boy, in swift and fluent Swedish that had, however, a trace of an American accent. He looked disappointed, and ran off to tell his pals that I was a phony. The woman turned back to me, smiling.

“You broke his heart,” she said.

“Yes,” I said. “Well, thanks a lot for interpreting.”

I got into the cab, leaving her standing there. She had quite a pretty smile, but if she had some reason besides my masculine appeal for wanting to talk to me, she’d undoubtedly turn up again; and if she didn’t, I had no time for her. I mean, I’ve never had any sympathy for agents who can’t refrain from complicating their jobs with irrelevant females. The relevant ones usually present problems enough.

I rode away without looking back, bracing myself against the psychological impact of the cockeyed traffic, which seemed even more unnatural because the cab was an ordinary American Plymouth with the steering wheel in the usual place. If they had to drive contrary to everyone else, you’d think they’d at least shift the driver over to where he could see the road. In addition to cars, the streets swarmed with ordinary bicycles, bikes with little motors, motor scooters, and full-grown motorcycles driven at furious speed by kids in round white crash helmets and black leather jackets.

At the hotel, I had to register on a police card that required me to state, among other things, where I’d come from last, how long I was staying here, and where I planned to go next. I was a little shocked to meet this sort of police-state red tape here, in time of peace. The Swedes were, after all, supposed to be among the most secure and democratic people in Europe, if not in the world, but apparently a foreigner had to be reported to the cops every time he changed hotels; and I wasn’t forgetting that bringing an ordinary rifle and shotgun into the country had demanded the equivalent of an act of Congress. I couldn’t help wondering what they were afraid of. Probably people like me.