The Year of Shadows (36 page)

Read The Year of Shadows Online

Authors: Claire Legrand

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #Fairy Tales & Folklore, #General, #Social Issues, #Friendship, #Action & Adventure

We came to slowly, just like we had died.

“

Bravi, bravi, bravissimi!

” Nonnie cried, applauding us. Igor blinked slowly from her lap.

For a long time, I just lay there. What do you do—how do you move again—after something like that?

“Sorry.” Mr. Worthington stretched out his hand to us, a dark, shimmering, barely-there splotch in the air. “Sorry.”

“Was it like a roller coaster,

ombralina

?” said Nonnie. “Did you zoom through the air?”

Henry had turned away from me, and his voice sounded funny. “Yeah, Nonnie. We zoomed.”

“A doll” was all I could say, because it was obvious. “That’s his anchor. We’ll have to find Tabby’s doll.”

MARCH

W

E KEPT MR. WORTHINGTON

close while we searched. Shades followed us everywhere, every day, their black jaws clacking. At night, while we slept, I heard clawed things clattering across the roof. Soft groans. Crashes from the attic, where the floor was too weak to store anything.

“The ceiling, it will fall!

Una catastrofe!

” Nonnie declared one evening after dinner, while I attempted to dust. The Maestro sat at the kitchen table, head in his hands as he studied the Mahler 2 score.

“Don’t worry, girls.” He smiled up at us. His eyes were red and watery. I wondered if he’d been sleeping, if he could hear what I’d been hearing. “The noises lately. Don’t worry about them. It’s only rats. I’ve already called an exterminator.”

I raised an eyebrow. “Rats?”

“No, no!” Nonnie shook her head. “Not rats.

Shades

. Olivia told me. They come, they drag you away!” She yanked her scarf through her fingers.

I couldn’t tell what the Maestro was thinking as I stood there, clutching the dust rag. I figured even the shades, crashing across the roof, could hear my heart pounding.

“Anyway, it doesn’t matter.” The Maestro returned to his music. “This . . .” He pointed at Mahler 2, his notes scrawled across the pages. His fingers shook. “This will make all the difference. She will come back. She will.”

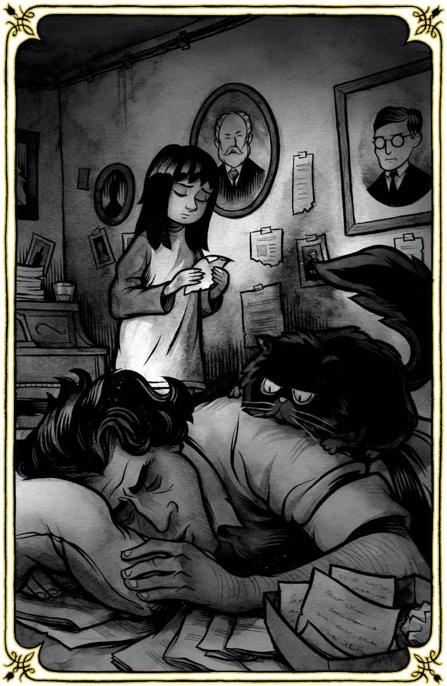

I backed away as quietly as possible. When I’d reached the hallway, I made a run for it, straight for Mrs. Bloomfeld’s office up front, and locked myself in. I picked up the phone, almost dialed Henry’s number—and stopped.

What exactly would I say to him?

The Maestro’s officially lost it. The Maestro thinks some symphony will bring back my mom.

I hung up the phone and started to pace, Mr. Worthington right beside me.

“I mean, he’s insane, right?” I kicked one of the file cabinets. It made a satisfying boom. “What, like some music he plays will magically call her back from wherever she’s gone? She could be halfway across the world, for all we know.”

Mr. Worthington nodded. “Halfway.”

“Right. So whatever. I don’t want to think about this anymore. He can think whatever crazy things he wants to, just as long as he keeps conducting.”

I flung open the door, marched back into the lobby—and stopped dead.

A single shade had curled around one of the marble

columns, peeking out at me. Its fingers had dug black grooves into the stone.

Something inside me boiled up at seeing it standing there, just waiting to attack. I rushed at it, baring my fingers like claws.

“Go away!” I screamed. “Get out of here!” I saw a stack of programs, freshly pressed and waiting for the next concert, sitting by the door. I grabbed them and flung them at the shade, hitting it square in the back as it scampered away. And for a second, I thought I heard the strangest thing—a sick little sound, like from a hurt dog.

Then it was gone, leaving me shaking in the middle of the lobby. Mr. Worthington hovered behind me, muttering, “Halfway, halfway,” over and over, like a prayer.

One day, I was so tired from searching for Tabby’s doll and going to school and work and practicing algebra (which had actually gotten kind of fun) that I fell asleep right after getting home from The Happy Place and didn’t wake up until two in the morning.

Mr. Worthington stood on his head in the middle of the room. He enjoyed trying different sleep poses.

I told him I needed a drink of water, made sure he was safely near Nonnie, and padded out of the room in my socks. Something pulled me through the silent backstage rooms. Instruments—a piano, a harp—stood silently in pale light streaming in from the windows. Some of the musicians had left their jackets hanging on chairs. The light coming in from outside froze dust particles in place like snow.

The Maestro had fallen asleep on his cot, right on top of—I tiptoed closer to look—the score for Mahler’s Symphony no. 2: “The Resurrection.”

When I shuffled past the Maestro’s bedroom, I saw his door standing open, just enough for a thin ray of light to escape.

I peeked inside.

The Maestro had fallen asleep on his cot, right on top of—I tiptoed closer to look—the score for Mahler’s Symphony no. 2: “The Resurrection.” What a surprise.

The Maestro rolled over onto his back, blowing the score open to the first page of the fourth movement, the

Urlicht

. He started to snore.

“Gross.”

Igor jumped into the room and onto the mattress.

At least he doesn’t drool.

“Oh, ha-ha.”

That’s when I saw the plastic box lying open between the Maestro and the wall, the letters lying in smashed piles underneath the Maestro’s cheek. I recognized those letters and the loopy handwriting that read: “

Dearest Otto . . .

”

Strange, how different the Maestro looked while sleeping. In fact, he looked about five years old with his mouth hanging open like that. Had he been reading these letters before bed?

Out from under his arm poked a triangular scrap of paper—the corner of a newspaper clipping.

I slid it out. The Maestro’s greasy fingers had smeared

some of the ink, but I could read it just fine. There weren’t a lot of words. But there were enough:

Waverly, Cara.

Waverly was Mom’s name, before she married the Maestro. My fingers shook. I thought I might drop the paper. Igor sat up on his haunches and put his paws on my wrist.

I took a deep breath and read on:

Waverly, Cara. Passed away 2/15. Memorial service to be held 3PM 2/21 at Pine Ridge Baptist, 5144 Grandison Road.

My brain couldn’t get past the words “Memorial service.”

“That’s right here in town,” I said. “She was here? But . . .”

Then I saw it, the ugliest, most unforgivable word I’ve ever known:

OBITUARIES.

I didn’t need Henry or Joan there to tell me what that meant. I knew. The realization sank into me, collapsing my insides.

It meant Mom was dead.

PART FOUR

“I

DON’T UNDERSTAND,”

I whispered.

Igor meowed softly.

Yes, you do. I think you’ve understood all along.

“But . . .” The newspaper fell to the ground, floating like Tillie swinging her way down from the rafters. The date on the newspaper was from just over a year ago. Last February.

“Olivia? What’s wrong?” The Maestro was yawning awake, reaching for me.

“Get away from me!” I slapped at his hands. “Don’t touch me!”

“Olivia, what in the world—?”

When he saw the obituary on the floor, a heaviness fell over him.

“Oh,” he said.

“Oh.”

I snatched the clipping and ran out to the stage, tumbling over my own feet. The Maestro followed me, and Mr. Worthington was right behind him, fretting.

“Olivia, allow me to explain—”

I thrust the obituary at his face. “How did it happen? How did she die?”

He flinched. Good. Let him flinch. He could flinch himself into a coma, for all I cared. That wouldn’t change the fact that Mom was dead—dead,

dead

—that I had found out like

this.

“It was a car accident,” he said simply. “They said—” He cleared his throat. “Olivia, they did say it was quick. She would not have felt tremendous pain. Cara’s mother—you remember Gram.”

I did. She’d never liked the Maestro, and I don’t think she’d ever liked me too much either; we looked too alike.

“She called me with the news. That’s how I found out.”

“I don’t care about that. Why didn’t you tell me?”

The Maestro put up his hands. “Olivia, you will wake your grandmother.”

“Oh, like you care about Nonnie.”

“But of course I—”

“Why didn’t you tell me? You’ve been lying to me. There was a memorial service. She was

here

, in this city, at that church. You kept her from me. All of you did!” My head spun. They must have known. The musicians, Richard Ashley, maybe even the Barskys. They all must have known.

“Kept,” Mr. Worthington muttered, pacing behind the Maestro. “Kept.”

“Olivia, you wouldn’t have wanted to go to that.”

“How do you know? You don’t know me at all.”

“She did not look like herself, Olivia, not at the end. She was broken all over.”

I tried to imagine what that would look like. I was an artist,

and artists had to examine even the awful things—

especially

the awful things—to find the truth.