Theodore Roosevelt Abroad (17 page)

Read Theodore Roosevelt Abroad Online

Authors: J. Lee Thompson

Figure 6

Kermit, TR, and an African Cape buffalo, Courtesy the Theodore Roosevelt

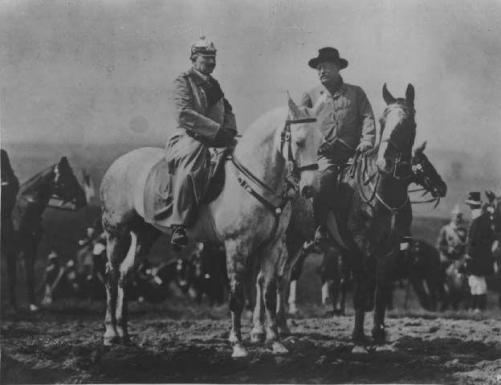

Figure 7

TR and the German Kaiser, May 1910. Courtesy the Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Harvard College Library.

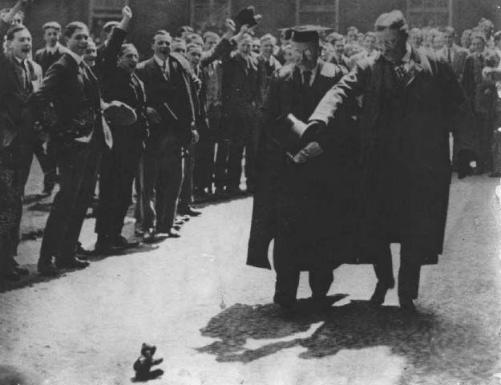

Figure 8

TR, on the far right, as Special Ambassador at the funeral of Edward VII, May 1910. Courtesy the Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Harvard College Library.

Figure 9

TR with a teddy bear at Cambridge Union, May 1910. Courtesy the Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Harvard College Library.

Figure 10

TR, waving his hat, welcomed back to New York in June 1910. His niece Eleanor and her husband Franklin Roosevelt stand by the smokestack. Courtesy the Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Harvard College Library.

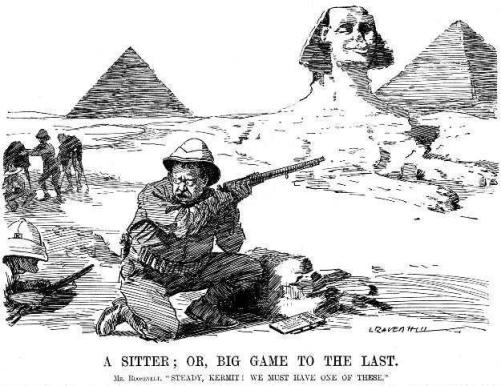

Figure 11

Punch

cartoon, March 23, 1910: TR and the Sphinx.

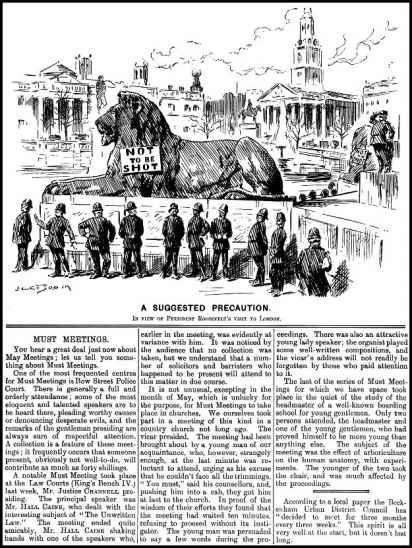

Figure 12

Punch

cartoon, May 11, 1910: Lion in Trafalgar Square with a sign reading “Not to be shot.”

Figure 13

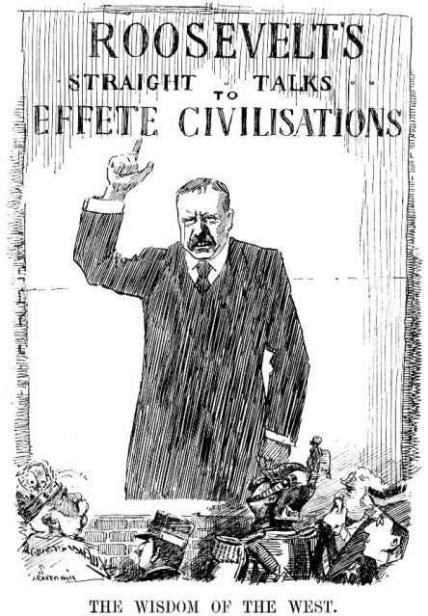

Punch

cartoon, May 4, 1910: “Roosevelt’s Straight Talk to Effete Civilisations.”

Chapter 5

Down the Nile: Khartoum to Cairo

A few days before the

Dal

reached Khartoum, a flotilla of boats carrying the journalists barred from the safari intercepted Roosevelt on the Nile. Among the newspapermen was at least one friendly face, John “Cal” O’Laughlin of the

Chicago Tribune

, who, as an acting assistant secretary of state at the end of TR’s administration, had been present at the final “tennis cabinet” gathering a year before. O’Laughlin recalled his first glimpse of a beaming TR on the deck of the

Dal

, dressed in khaki and under an American flag swinging his olive green helmet in reply to the frantic hat waving of the press who crowded the railing of his vessel, the

Abbas Pasha

. Roosevelt had lost the care worn look O’Laughlin remembered from the last White House days, his face was brown, his moustache lightened by the sun showing “more than a few gray hairs.” He heartily welcomed the journalists as the “vanguard” of the civilization he had left behind a year before.

1

The pressmen were eager to quiz the former president about his journey and to ask his opinion of President Taft, who had been left in charge explicitly to carry on Roosevelt’s policies, but had instead, as we have seen, among other things supported the controversial PayneAldrich Tariff and dismissed TR’s man Gifford Pinchot from the Department of Forestry. The Colonel, however, was willing to discuss such matters only “off the record” and told each as he spoke to them separately that anything they published would be denied. He would only authorize the statement that he had nothing to say about politics. Of course Roosevelt’s silence only led to ominous headlines to that effect in the U.S. papers. Jusserand sent one such clipping to him along with a letter in which he declared that “It is pleasant to think that Africa has not changed you in any way . . . Mute you went into the desert, dumb you return.” In addition to sharing the itinerary which he had drawn up for TR’s visit to Paris, the Frenchman told Roosevelt that he had gone to the Smithsonian for a glimpse of the fruit of his labors. “But we found there under glass, only 2 or 3 skulls, 2 rats and one hedgehog.” They were assured, however, that before long “your expedition would make a better show in the museum.”

2

At Khartoum on March 14 the local British officials once again greeted Roosevelt with “more than friendly enthusiasm.” He stayed at the yellow stucco Governor’s Palace, where twenty-five years before, General “Chinese” Gordon had been slain by the jihadist dervishes of the Mahdi. To TR’s great regret the Governor-General, Sir Reginald Wingate, had been forced to Cairo by an illness and in his absence the Colonel’s host was Sir Rudolph Slatin Pasha, the inspector-general. An Austrian soldier who had joined the Turco-Egyptian administration in the Sudan, Slatin had been imprisoned by the Mahdi and had endured more than a decade of captivity of one sort or another. He made his name (and that of Wingate who had played a part in his escape) by recounting his harrowing tale in

Fire and Sword in the Sudan

.

3

This Roosevelt had devoured and he peppered a surprised Slatin with questions and observations.

The

Dal

docked just in time for TR and Kermit to meet the train which carried Edith and Ethel south from Wadi Halfa. After their separation of just ten days less than a year, Theodore’s homesickness and Edith’s worries both vanished at the rail station. She found her husband in “splendid condition” and noted that he had “lost that look of worry and care” which had been “almost habitual” in the White House years. Edith was also heartened to see that the adventure in Africa had transformed her beloved Kermit from pale youth to tan and sturdy manhood.

4

She even approved of the wisp of a moustache he had grown. Edith brought along clothes for both men and at Khartoum Roosevelt shed his khaki safari accoutrements, donning a gray sack suit. As a reward for her forbearance of his yearlong safari, Theodore meant to give his wife a prolonged second honeymoon in Europe, which she had also scouted in her own peregrinations over the past year, but almost all their plans were scuppered by events.

At Khartoum, Roosevelt finished a “preliminary statement” summing up the accomplishments of the expedition, which he dispatched to Walcott. In this he noted that Heller had prepared 1,020 mammal specimens, mostly large, while Loring had prepared 3,163 and Mearns 714, for a total of 4,897 mammals. Almost 4,000 birds had also been prepared, almost all by Mearns and Loring. To these mammals and birds were added about 2,500 reptiles, amphibians, and fish, for a grand total of 11,397, not including thousand of invertebrates and plants.

5

TR also regretfully said goodbye at Khartoum to his companions of the last year, the expedition’s hunters and naturalists, all of whom he came greatly to like and respect. He wrote to Leslie Tarlton a few months later, “you do not need to be told my feelings for you, and for that old trump R. J. [Cuninghame]. I shall always count you both as among my real friends.”

6

In his report to Walcott, the Colonel declared that the hunters had “both worked as zealously and effectively for the success of the expedition as any other member.”

7

Loring and Mearns had proved indefatigable collectors of small animals and birds, while Heller and Roosevelt collaborated on a two-volume study, published four years later as

Life-Histories of African Game Animals

, a significant contribution to the scientific literature. No three better men, TR wrote, “could be found anywhere” for such an expedition as theirs. He and Kermit also had a sad parting from “our faithful black followers, whom we knew we should never see again.” It had been an interesting and a happy year but he was “very glad to be once more with those who are dear to me, and to turn my face toward my own home and my own people.”

8

From Khartoum, TR had hoped to travel as a private citizen and even to handle all the family’s travel arrangements himself. However, as with the safari, he soon had to admit the impossibility of this notion and accepted the volunteer services of two members of the press contingent, who were also friends, Cal O’Laughlin, and Lawrence Abbott of the

Outlook

, which TR had agreed to join as a contributing editor once he returned to America. Roosevelt had invited Abbott to meet him at Khartoum and he had escorted Edith and Ethel down from Cairo. The pair acted as private secretaries to Roosevelt until he reached England.

9

Both men, with the Colonel’s blessing, took advantage of their position to send home articles detailing the trip and TR’s view of things, international and domestic.

10