There is No Alternative (41 page)

Read There is No Alternative Online

Authors: Claire Berlinski

When faced with the choice between strengthening Britain's ties to Europe and strengthening its ties to the United States, Thatcher did not even try to find a tactful middle ground:

Interviewer:

I've heard it said by a lot of people that President Reagan appears to be wanting to be seen to be very strong militarily, yet some people have the thoughts that in Europe the feeling is just a little bit softer, with not quite as much determination as President Reagan has. Where do you stand between the two trains of thought?

I've heard it said by a lot of people that President Reagan appears to be wanting to be seen to be very strong militarily, yet some people have the thoughts that in Europe the feeling is just a little bit softer, with not quite as much determination as President Reagan has. Where do you stand between the two trains of thought?

Giant protests erupted in mainland Europe and Britain against the United States' plans to deploy cruise and Pershing missiles in

response to the Soviet deployment of the Satan. This antinuclear sentiment blossomed into a mass movement financed by the Soviet Union and supported, in Britain, by the Labour Party. “All over Europe,” recalled Reagan, “the peace marchers demonstrated to prevent Western missiles from being installed for their defense, but they were silent about the Soviet missiles targeted against them! Again, in the face of these demonstrations, Margaret never wavered.”

208

response to the Soviet deployment of the Satan. This antinuclear sentiment blossomed into a mass movement financed by the Soviet Union and supported, in Britain, by the Labour Party. “All over Europe,” recalled Reagan, “the peace marchers demonstrated to prevent Western missiles from being installed for their defense, but they were silent about the Soviet missiles targeted against them! Again, in the face of these demonstrations, Margaret never wavered.”

208

The first cruise missiles arrived at Greenham Common in December 1983, inaugurating a permanent state of protest at the U.S. air base. Thatcher scolded the protesters: “We are very fortunate to have someone else's weapons stationed on our soil to fight those targeted on us.”

209

Although this was perfectly true, she sounded to her detractorsâas she so often didârather like Mr. Bumble informing Oliver Twist that he was very fortunate to have gruel every day with an onion twice a week.

209

Although this was perfectly true, she sounded to her detractorsâas she so often didârather like Mr. Bumble informing Oliver Twist that he was very fortunate to have gruel every day with an onion twice a week.

Mr. Faulds:

Reverting to an earlier supplementary question on the subject of theater nuclear weapons, will the right hon. Lady contemplate where that intended theater lies? Will each European Government be free to choose or to veto the push on that final button by that incoherent cretin, President Reagan?

Reverting to an earlier supplementary question on the subject of theater nuclear weapons, will the right hon. Lady contemplate where that intended theater lies? Will each European Government be free to choose or to veto the push on that final button by that incoherent cretin, President Reagan?

The Prime Minister:

I greatly deplore the discourtesy and total futility of the hon. Gentleman's remarks.

I greatly deplore the discourtesy and total futility of the hon. Gentleman's remarks.

Mr. Faulds:

Answer the question!

Answer the question!

The Prime Minister:

They do not help when the security of Europe depends upon the support of the United States of America. With regard to the theater nuclear weapons, the SSâ20s are targeted on Europe, including this country.

210

They do not help when the security of Europe depends upon the support of the United States of America. With regard to the theater nuclear weapons, the SSâ20s are targeted on Europe, including this country.

210

There was one notable moment of dissent: When in 1983 the United States invaded Grenada, a member of the British Commonwealth, without first notifying the British government, Thatcher was furious. She nonetheless held her tongue in public, even while expressing her extreme displeasure with Reagan in private.

Mr. Kinnock:

Is it not a fact . . . that the relationship that was said to exist between the right hon. Lady and the President turned out to be not so special? In the chaos and humiliation of the Grenada affair, will the right hon. Lady at least take the opportunity of adopting a new deportment in world affairs and, as a consequence, demonstrate a greater independence in furthering British interests and working for peace throughout the world?

Is it not a fact . . . that the relationship that was said to exist between the right hon. Lady and the President turned out to be not so special? In the chaos and humiliation of the Grenada affair, will the right hon. Lady at least take the opportunity of adopting a new deportment in world affairs and, as a consequence, demonstrate a greater independence in furthering British interests and working for peace throughout the world?

The Prime Minister:

When two nations are friends each owes the other its own judgment. That does not mean that the other in either case is compelled to accept it. It would hardly be a friendship unless one could tender advice to another countryâ

When two nations are friends each owes the other its own judgment. That does not mean that the other in either case is compelled to accept it. It would hardly be a friendship unless one could tender advice to another countryâ

Mr. Foulkes:

And have it ignored!

And have it ignored!

The Prime Minister:

âand have it either accepted or rejected. We do not run the sort of Warsaw pact organization that the right hon. Gentleman

â

[

Interruption

]

âand have it either accepted or rejected. We do not run the sort of Warsaw pact organization that the right hon. Gentleman

â

[

Interruption

]

Mr. Kinnock:

I would be the last to suggest the rendering of any alliances, but when the judgment of this Government is apparently utterly cast aside and trampled on by our ally, what obligation does the right hon. Lady then have?

I would be the last to suggest the rendering of any alliances, but when the judgment of this Government is apparently utterly cast aside and trampled on by our ally, what obligation does the right hon. Lady then have?

The Prime Minister:

It follows from what the right hon. Gentleman has said that, as the United States and Britain are allies, we would always have had to accept any advice that the United States gave us. Indeed, it follows that we would not be free to accept or reject the advice of the United States. However, at the beginning of the Falklands affair we did not ask the United States whether we should recapture the Falklands. We took our own decisions.

It follows from what the right hon. Gentleman has said that, as the United States and Britain are allies, we would always have had to accept any advice that the United States gave us. Indeed, it follows that we would not be free to accept or reject the advice of the United States. However, at the beginning of the Falklands affair we did not ask the United States whether we should recapture the Falklands. We took our own decisions.

By publicly supporting Reagan when he was most isolated abroad, Thatcher won Reagan's trust and earned his gratitude. Ultimately, and in large part owing to her sheer, dogged loyalty, her influence on Reagan came to exceed that of most of his cabinet members. That influence proved pivotal when Mikhail Gorbachev came to power.

In November 1984, roughly a year after the downing of KAL 007, the Soviets walked out of the Geneva talks on intermediate-range missiles. They then walked out of the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty discussions on long-range missiles, breaking off all contact with the United States. There was now no personal contact between American and Soviet leaders.

This extraordinarily dangerous impasse, Thatcher believed, made it incumbent upon her to take the diplomatic initiative. She rejected Geoffrey Howe's suggestion that she invite the Soviet premier, Konstantin Chernenko, to visit Britain. She was not prepared to be that friendly. Instead, she issued invitations to several lower-ranking members of the Politburo. The Soviet agricultural secretary, a man by the name of Gorbachev, responded with interest.

Thatcher knew little about Gorbachev save that his wife was reputed to be less unattractive than the wives of the other Soviet leaders. In 1984, there was no reason beyond this to expect that Gorbachev would be much different from the other walking corpses of the Soviet leadership. Gorbachev had never visited the United States. He had never met Reagan. Still furious with the Soviets, Reagan had shown no interest in meeting him. But this Gorbachev fellow seemed keen to come to Britain, so Thatcher asked him to join her for lunch, at Chequers, on December 16.

Charles Powell remembers Gorbachev's arrival at Chequers vividly. “It was an extraordinary moment. You won't have seen Chequers, but it's an old English country house, with a great hall at the entrance, a huge fire, a few members of the government

standing thereâand nobody had

any

clue what to expect. I mean, Gorbachev was not known outside the Soviet Union. He'd once been outside to Canada.

211

Nobody had taken any notice of him. He came into this room, beaming, bouncing on the balls of his feet, this smartly dressed wife with him, and everyone present just simply had to change gear . . .

this is not Khrushchev, this is not Andropov, this is not Chernenko, this is an entirely new sort of person.

He engaged from the beginning in jovial banter with people and ordered a drink before lunch. Then he and Margaret Thatcher sat next to each other at lunch, and neither of them ate a thing. They spent the whole time talking at each other, and arguing about thingsâ”

standing thereâand nobody had

any

clue what to expect. I mean, Gorbachev was not known outside the Soviet Union. He'd once been outside to Canada.

211

Nobody had taken any notice of him. He came into this room, beaming, bouncing on the balls of his feet, this smartly dressed wife with him, and everyone present just simply had to change gear . . .

this is not Khrushchev, this is not Andropov, this is not Chernenko, this is an entirely new sort of person.

He engaged from the beginning in jovial banter with people and ordered a drink before lunch. Then he and Margaret Thatcher sat next to each other at lunch, and neither of them ate a thing. They spent the whole time talking at each other, and arguing about thingsâ”

Â

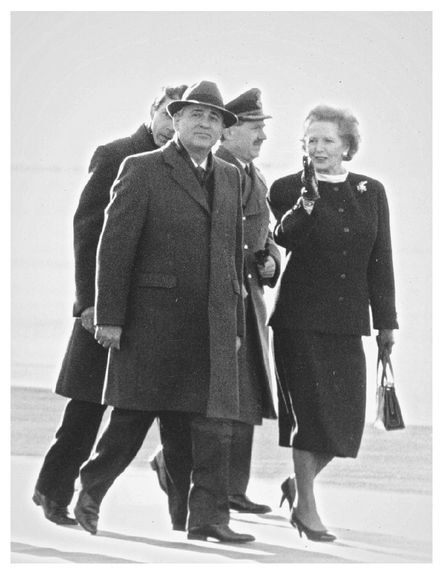

Thatcher walking with Gorbachev at the Brize Norton Air Force base in 1987. “Certainly the two leaders were attracted to each other, relished each other's company,” recalled her Foreign Secretary Geoffrey Howe. “But neither Margaret nor Mikhail ever completely lowered their guard.”

(Courtesy of Graham Wiltshire)

(Courtesy of Graham Wiltshire)

“Right from the start? Arguing right from the start?”

“Well, arguing was sort of Thatcher's

raison d'être

â”

raison d'être

â”

“It sounds as if he sort of got that right away, understood it, related to it?”

“Oh, yes, absolutely. He

enjoyed

it. And then we retired into another room. It was just him, and her, and me, and the then Soviet ambassador here, and that man from the Politburo who was Gorbachev's great ally, he'd been exiled to be ambassador to Canada, and whose name now escapes me, began with K.

212

And in that small room, they talked for two and a half hours as against the half-hour scheduled. Gorbachevâimmediately, again, you

saw

the difference. I mean, the advisors just shut up. He had no briefs, no documents, he had a few little handwritten notes in green ink, which he occasionally produced, the odd newspaper clipping from the

Wall Street Journal

or the

New York Times

âone was about nuclear war, I remember particularly. About nuclear winter. And he talked absolutely self-confidently and assuredly, and he wasn't even leader at the time. Chernenko was still in charge. Gorbachev was still just a member of the Politburo, technically in charge of agriculture. This was new ground . . . I mean, we'd had this succession of geriatrics, Chernenko, and before him Andropov and Brezhnev, who could barely stand up and who just sort of read from bits of paper. Here was a man who talked and argued like a

Western politician, didn't need briefs and notes and advisorsâand he sat there and slugged it out with her! This was somebody you could really

engage

with.”

enjoyed

it. And then we retired into another room. It was just him, and her, and me, and the then Soviet ambassador here, and that man from the Politburo who was Gorbachev's great ally, he'd been exiled to be ambassador to Canada, and whose name now escapes me, began with K.

212

And in that small room, they talked for two and a half hours as against the half-hour scheduled. Gorbachevâimmediately, again, you

saw

the difference. I mean, the advisors just shut up. He had no briefs, no documents, he had a few little handwritten notes in green ink, which he occasionally produced, the odd newspaper clipping from the

Wall Street Journal

or the

New York Times

âone was about nuclear war, I remember particularly. About nuclear winter. And he talked absolutely self-confidently and assuredly, and he wasn't even leader at the time. Chernenko was still in charge. Gorbachev was still just a member of the Politburo, technically in charge of agriculture. This was new ground . . . I mean, we'd had this succession of geriatrics, Chernenko, and before him Andropov and Brezhnev, who could barely stand up and who just sort of read from bits of paper. Here was a man who talked and argued like a

Western politician, didn't need briefs and notes and advisorsâand he sat there and slugged it out with her! This was somebody you could really

engage

with.”

The then Soviet ambassador to whom Powell is referring was a man named Leonid Zamyatin. “This was how it went,” Zamyatin remembered. “They sat down in armchairs at a fireplace, Thatcher took off her patent-leather shoes, tucked her feet under her chair and got out her handbag.”

213

213

I've spoken now to many men who specifically remember Thatcher kicking off her shoes and curling up her feet in that flirtatious way. I have looked in vain for a photo or video clip that shows her doing this. It seems she never did it with a camera present. She was obviously well aware that it was a coquettish and provocative gesture, and well aware, too, that “barefoot and cuddly” was not the image she wished, as a world leader, to project widely.

I have pieced together what happened next from several different accountsâher memoirs, Gorbachev's memoirs, Powell's recollections, Zamyatin's, various official memoranda of the meeting. I am fairly sure that it went roughly this way:

Gorbachev suddenly suggested they both get rid of their briefing papers.

“Gladly!” replied Thatcher, putting her papers back in her handbag.

Gorbachev told Thatcher it was time to end the Cold War.

Thatcher told Gorbachev it was time to end communism.

Gorbachev told Thatcher that communism was superior to capitalism.

“Don't be silly, Mr. Gorbachev. You can barely feed your own citizens.”

“To the contrary, Mrs. Thatcher! Our people live

joyfully.

”

joyfully.

”

“Oh, do they? Then why do so many of them want to leave? And why do you prevent them from leaving?”

“They can leave if they want to!”

“That's not what I hear. And by the way, we're not happy about the money you're sending to Arthur Scargill.”

“We have nothing to do with that.”

“Who do you think you're kidding? You and I both know that your economy is centrally controlled. Not a kopeck leaves without the Politburo's knowledge.”

“

Nyet, nyet,

you misunderstand. It's not centrally controlled.”

Nyet, nyet,

you misunderstand. It's not centrally controlled.”

“Oh, no? How does a Russian factory decide how much to produce?”

“We tell them.”

Perhaps Thatcher laughed. Perhaps she snorted. I like to imagine that her gifted mimic of a translator laughed or snorted along with her even as the Soviet translator remained a leaden lump. “The Soviet Union and the West,” she said, “have entirely different ways of life and government. You don't like ours, we don't like yours. But it is in our common interestâindeed it is our dutyâto avoid a conflict.”

“But the United States has been targeting us with missiles since the 1950s!”

“Of course it has. You've been trying to export communism by force. Your missiles are aimed at us. What did you expect?”

I can't determine what Gorbachev said next. But something prompted Thatcher to tell him that Reagan was an honorable man. When he took office, he had put his heart and soul into writing a letter to Brezhnev. He had written it by hand. After months of silence, he received only a typed, pro forma reply.

Other books

Fatal Tide by Iris Johansen

ARC: Peacemaker by Marianne De Pierres

Dominion of the Damned by Bauhaus, Jean Marie

Breaking Your Dog's Bad Habits by Paula Kephart

Driving on the Rim by Thomas McGuane

Wingless by Taylor Lavati

To Reap and to Sow by J. R. Roberts

Barbara Metzger by Snowdrops, Scandalbroth

Savage Lane by Jason Starr

She's Gone: A Novel by Emmens, Joye