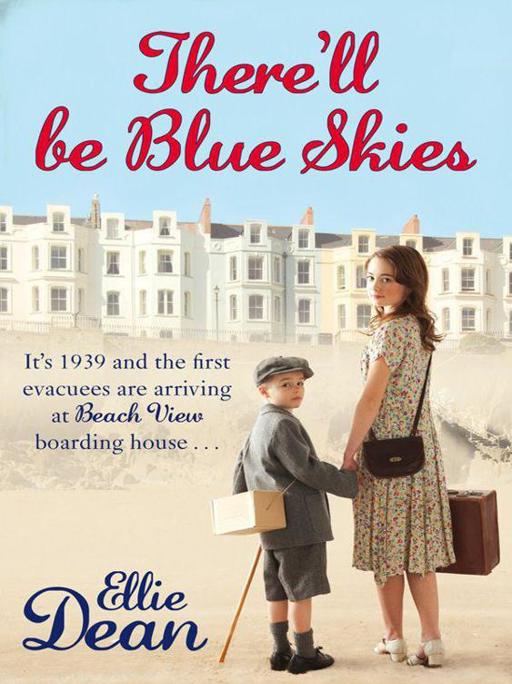

There'll Be Blue Skies

Contents

About the Book

When sixteen-year-old Sally is evacuated to the English south coast, she is terrified by what lies ahead of her. All she knows are the sights and sounds of London’s East End – but Sally swallows her tears as they leave the familiar landmarks behind, knowing that she has to be a Grown-Up Girl and play mother to her six-year-old brother Ernie. Playing mother is nothing new for Sally – their real mother Florrie, a good-time girl, hasn’t even come to the station to wave them off and Ernie, crippled at an early age by polio, is used to depending on his older sister.

When they arrive in Cliffehaven, they’re taken to live at the Beach View Boarding House where they’re welcomed by the open-hearted Reilly family headed up by warm, loving Peggy, and life begins to improve. Sally gets a job in a uniforms factory to help pay her way – and to pay for Ernie’s expensive medicines – but then Florrie arrives in Cliffehaven, bringing disaster with her. And Sally is forced to work out where her true loyalties lie…

Fiction

About the Author

There’ll be Blue Skies

is Ellie Dean’s first novel. She lives in Eastbourne, which has been her home for many years and where she raised her three children.

Acknowledgements

There’ll be Blue Skies

is set in a time before I was born, so I have had to pester many people to help me make the story as authentic as possible.

Edie Brit, you’re a star! Thank you so much for giving me the many insights into how life was in a seaside town during WW2. Your input was invaluable. Thanks too, to Brian Putland for introducing us.

I would also like to thank my mother-in-law, Kathleen Cater, and her friend, Jean Lane, for answering all my questions, and to Paul Nash for the information on southern RAF stations, life on the south coast during WW2, and the many hours you must have spent trawling through your extensive library. To Mick Barrow at the Hastings Fisherman’s Museum, the staff at the Eastbourne Lifeboat Museum, and the curator at Newhaven Fort, I am most grateful for your time and your generosity in sharing your vast knowledge. A huge thank-you also goes to the hundreds of people who have posted their war memories on the Internet. I’ve pinched a few comic – and not so comic – incidents I hope you don’t mind.

Lastly, I would like to acknowledge the unswerving loyalty of my literary agent, Teresa Chris, and the support, faith and guidance given by my editor, Georgina Hawtrey-Woore. Without these two brilliant women, this book would never have been written.

Chapter One

The threat of war had been the talk of the East End and, although Sally Turner had little idea of what it would really mean, she’d heard enough of the old men’s tales to know it would probably be the most frightening thing she could ever experience. After the rumours and fears had been confirmed in Chamberlain’s declaration, she could see the changes in the narrow streets and alleyways of Bow, for many of the children had already been sent to the countryside. Now it was her turn to leave with her little brother, and the thought of being taken far from the sights, sounds and smells of the only place she knew was terrifying.

She carefully placed the birthday card on top of their clothes, closed the battered suitcase, and secured it with one of her father’s old belts. It was the only card she’d received and, as it had come from her father, it was extra special, and not something to be left behind. Harold Turner was already at sea when war was declared, and she had no idea where he was – but he’d remembered she’d turned sixteen a month ago, and it made her adore him even more. Her mother, Florrie, had forgotten as usual.

‘Where’s Mum?’ Ernie was sitting on the end of the sagging couch which pulled out as a bed. He and Sally slept there every night unless Florrie was entertaining – then they went downstairs to Maisie Kemp’s. ‘I want Mum.’

Florrie hadn’t come home last night and Sally could have done with knowing where she’d got to, but she had her suspicions. The pubs, clubs and streets in the East End were heaving with servicemen looking for a bit of fun – and Florrie liked a good time. ‘She’s probably gone off to work early,’ she said, calmly.

‘Mum never goes to work early,’ he muttered.

Sally wasn’t willing to get into an argument over their mother’s whereabouts. Ernie was only six. ‘There’s a war on,’ she said, instead. ‘Everyone’s got to do their bit – including Mum.’

Ernie’s clear brown eyes regarded her steadily. ‘Old Mother Kemp says Mum’s doing ’er bit all right, and that Dad wouldn’t like it. What did she mean by that, Sal?’

Maisie Kemp should learn to keep her trap shut around Ernie, thought Sally. ‘I don’t know, luv. Now, sit still and let me sort you out or we’ll never be on time.’ She tucked her fair curls behind her ears and picked up the special boot which she eased carefully over Ernie’s misshapen foot. Once the laces were tied, she began to buckle the leather straps round his twisted, withered leg.

The polio had struck just before Ernie’s second birthday, and it had left him with a crippled leg and weakened muscles – but, despite his disability, Ernie was like any other six year old – full of cheeky mischief and far too many questions.

‘Do we ’ave to go, Sal?’

She made sure the callipers weren’t too tight and patted the bony knee that jutted from beneath the hem of his short trousers. ‘The prime minister says we ’ave to get out of London cos it ain’t safe. All yer mates are going, and you don’t want to be left out, do ya?’

Ernie shrugged and pulled a face. ‘Why can’t Mum come with me?’

‘Because she can’t – now, where did you put your school cap?’

He pulled it out of his pocket and rammed it on his head before tugging on his blazer. ‘Will I ’ave to go to school? Billy Warner says there ain’t no school in the country, just cows and sheep and lots of poo.’ He giggled.

Sally giggled too and gave her little brother a hug. ‘We’ll have to just wait and see, won’t we?’ She made him a sandwich with the last of the bread and dripping. ‘Eat that while I tidy up, then we must be going.’

It didn’t take long to strip the bedding off the couch, finish the washing-up, and collect the last few things to take with them. Their home consisted of two rooms on the top floor of a house, which was in a sooty red-brick terrace overshadowed by the gas-works and Solomon’s clothing factory, where she had worked for the past two years alongside her mother.

Florrie had the only bedroom; the sitting room, where Sally and Ernie slept, doubled-up as a kitchen, with sink, gas ring and cupboards at one end. There was no bathroom, water had to be fetched from the pump at the end of the street, and the outside lav was shared with four other families. Baths were once a week in a metal tub on the strip of lino in front of the gas fire.

Sally had lived there all her life and, as she helped Ernie on with his mackintosh, she felt a tingle of apprehension. The journey they were about to begin would take them far from London, and although she’d run the house and raised Ernie since his illness, she was worried about the responsibility of looking after him so far from the close-knit community which could always be relied upon to help. She had never been outside the East End, had only seen pictures of the country, which looked too empty and isolated to be comfortable – or safe.

Putting these doubts firmly away, she covered the precious sewing machine with a cloth and gave it one last, loving pat. It had been her grandmother’s, and the skills she’d taught Sally had meant she could earn a few extra bob each week. But it was part of a heavy, wrought-iron table which housed the treadle. It had to be left behind. She hoped it survived – and that Florrie didn’t take it into her head to sell it.

With a sigh, she squashed the worn felt hat over her fair curls, pulled on her thin overcoat and tightly fastened the belt round her slender waist. She then gathered up handbag, gas masks and suitcase before handing Ernie his walking stick.

‘I ain’t using that,’ said Ernie with a scowl.

‘It ’elps you to keep yer balance,’ she said, tired of this perpetual argument. ‘Come on, luv. Time to go.’

He snatched the hated stick from her and tucked it under his arm. ‘Do I ’ave to wear this, Sal?’ He plucked at the cardboard label hanging from a buttonhole on his school mackintosh. ‘Makes me look like a parcel.’

‘Yeah, you do. It’s in case you get lost.’

‘I ain’t gonna get lost, though, am I?’ he persisted. ‘You’re with me,’ he retorted with the blinding logic of the young.

She smiled at him. ‘Just wear it, Ernie, there’s a good boy.’ She locked the door behind her and put the key under the mat before helping him negotiate the narrow, steep stairs that plunged into the gloom of the hall.

‘Yer off then.’ Maisie Kemp had just finished scrubbing the front step, her large face red beneath the floral headscarf knotted over her curlers. She groaned as she clambered off her knees and wiped her hands down the wrap-round pinafore, before taking the ever-present fag out of her mouth. ‘Give us a kiss then, Ernie, and promise yer Auntie Maisie you’ll be a good boy.’

Ernie squirmed as the fat lips smacked his cheek, and he was smothered in her large bosom.

‘No sign of Florrie then?’ The blue eyes were knowing above the boy’s head, the expression almost smug.

‘Mum’s meeting us at the station,’ said Sally, unwilling to admit it was highly unlikely she’d even remembered they were leaving today. ‘Cheerio, Maisie, and best of luck, mate. See you after the war.’

She clutched the suitcase with one hand and Ernie’s arm with the other. Maisie could talk the hind legs off a donkey, and if they didn’t get away quickly, they’d be later than ever.

Their slow progress down the cracked and weed-infested pavement was made slower as the women came out of their houses to say goodbye, and the remaining children clustered round Ernie. Not all of them would be leaving London, but Sally and her mother had been forced to accept that Ernie’s incapacity meant he would be more vulnerable than most once the bombing started. It was also why he had to be accompanied – and as Florrie had flatly refused to leave London, Sally had no choice but to give up her job at the factory and go with him.

Ernie let go of her hand, and abandoned the walking stick as they came in sight of his school. He hurried off to join the swarm of chattering children, the calliper and thick special boot giving an added, stiff swing to his awkward gait.

Sally kept an eye on him as she joined the cluster of tearful women at the bus stop. If he got overexcited, his muscles cramped, and it would do him no good just before their long journey. With this thought she had a sharp moment of panic. Had she remembered his pills? She dipped into her coat pocket and let out a sigh of relief. The two little bottles were snug and safe.

‘I wish I were going with you,’ sobbed Ruby, her best friend. ‘But what with the baby to look after and me job at the factory …’

Sally rubbed her arm in sympathy. ‘Don’t worry, Rube. I’ll keep an eye on the boys for as long as I can – and we’ll all be back again soon enough. You’ll see.’

Ruby blew her nose, her gaze following the eight-year-old twins as they raced around the playground. ‘I’m gonna miss the little buggers and that’s a fact,’ she muttered, clasping the baby to her narrow chest. ‘The ’ouse ain’t gunna feel the same without ’em, especially now me old man’s gone off to war.’