They Marched Into Sunlight (44 page)

Read They Marched Into Sunlight Online

Authors: David Maraniss

Tags: #General, #Vietnam War; 1961-1975, #History, #20th Century, #United States, #Vietnam War, #Military, #Vietnamese Conflict; 1961-1975, #Protest Movements, #Vietnamese Conflict; 1961-1975 - Protest Movements - United States, #United States - Politics and Government - 1963-1969, #Southeast Asia, #Vietnamese Conflict; 1961-1975 - United States, #Asia

Three knocks on a block of wood.

Life absurdly mocking art: How could Sergeant Willie Johnson’s favorite song, his superstitious incantation,

knock, knock, knock on wood,

carry such lethal meaning?

P

RIVATE FIRST CLASS

B

REEDEN

was the first to die. Clifford Lynn Breeden Jr., aged twenty-two, from Hillsdale, Michigan. He was point man in Gribble’s squad on the front right file and the first to cross the trail. A burst of enemy fire struck him as he was setting up his own hasty ambush. Six bullets ripped open his chest and guts. He fired a clip from his M-16 and slumped to the jungle floor.

The opening spray slanted down from trees to the right, or west, followed by a thrum of machine-gun fire coming in low from the front. Jerry Lancaster fell next, and Leon East, and Gribble was losing his squad. He called to Sergeant Johnson that his men had been hit—Ray Neal Gribble’s last transmission. Johnson moved the remainder of the right file forward, directing his troops to get down and face the front and right. The point squad from his platoon’s left file cut across toward the right, and Captain George called his second platoon forward to reinforce the first.

The opening fusillade echoed back through the woods to the rear platoon of Delta. What was it? Some soldiers in the rear assumed it was Alpha springing its ambush. It sounded like the sort of skirmish the Black Lions had been getting in day after day that October. Contact, a quick firefight, the Americans pulling back to call in artillery and air, the Vietnamese disappearing as suddenly as they came. But this time, up and down the line, sniper fire started pinging down from the trees.

Terry Allen called Alpha and asked the company commander for a situation report. Jim George relayed what he heard and saw in front of him, but he could not say much about the first platoon because he was having trouble raising anyone on the radio. He yelled for Sergeant Johnson. No reply. It sounded bad, but was it? Allen told George to move forward to survey the scene. George crawled through heavy brush with the five-man Alpha command group. It was slow moving, but they eventually found Johnson and the point troops pinned down by machine-gun fire. The machine gun was hidden behind a low bunker protected by a dirt-covered log. It was about fifteen meters away, pointing east and detectable only by the trace of bullets. George pulled a hand grenade and flipped it over his shoulder in the direction of the fire, and in so doing revealed his position. The enemy gun turned on him, but the bullets missed and George could see the muzzle flash. He opened up with his Car-15 and silenced the machine gunner.

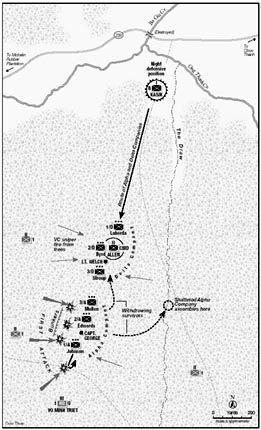

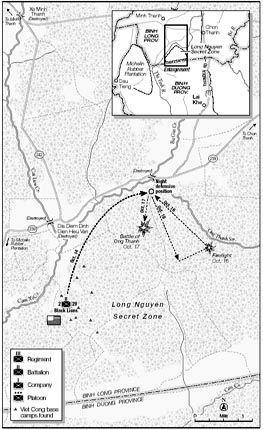

Movements of 2/28 Black Lions

Moments later one of Triet’s men sprang from the thicket with a thirty-six-inch handmade claymore mine and faced it toward the Alpha soldiers. It popped prematurely, killing the man who carried it and ripping out a tree, tearing it to pieces, yet the detonation was so close and powerful that it lacerated George’s command group and soldiers nearby. The blast zone was littered with blood and body parts. His company radioman, Michael Farrell, was dead. Others were wounded, including Alpha’s artillery forward observer. Men screamed for medics. “I’m hit, Top!” Willie Johnson yelled to Top Valdez. Welts were forming along his arms from the hot, flying shrapnel.

Captain George was struck in the face. The sharpest gash was at his left cheekbone, near his eye. His vision was poor already (he had needed glasses but had not been able to get them in Vietnam), and now in the aftermath of the claymore blast his sight was reduced to a blur of silhouettes. The concussion also ruptured an eardrum. He was supposed to be in command, but he was going deaf and nearly blind. On the ship across the Pacific, George had dreamed of killing fields and had grown weary of what he imagined to be the smell of death. Illusion and reality now merged in this jungle south of the Ong Thanh stream. In a fog he crawled back and to the east, away from the dead zone. He tried to stay low, but also told himself to keep his shattered face above the dirt. He yelled for Top Valdez, but his voice was not loud enough, so he sent an aide out to find the first sergeant. He radioed the battalion commander that he had been hit and was trying to break contact and that he had already lost a radiotelephone operator. “I understand,” said Allen, who had been driven by sniper fire to take cover behind a four-foot anthill.

No sooner had Willie Johnson regained his equilibrium than he was hit again, this time in the leg by AK-47 fire. Valdez reached Johnson and tied a handkerchief around his bleeding leg, then heard George’s shout and moved toward the captain.

Take over,

George said to him.

From his position near Alpha’s rear, Lieutenant Mullen, leader of the third platoon, responded instinctively when he heard a radio squawk that Willie Johnson had been hit. Before being promoted to command the first platoon, Johnson had been Mullen’s platoon sergeant in the third, and more than that, his mentor in the field, teaching him much of what he knew about jungle fighting. Mullen rushed toward the point to see if he could help, bringing along one soldier and his radiotelephone operator. They had moved no more than a few dozen meters when they saw Johnson being carried back down the column behind them. Mullen stopped momentarily, then was hit by “a tremendous volume of fire” along the flank that knocked him to the ground, unconscious. Only a few minutes into the fight and Alpha’s command was shattered: the company commander and two of his platoon leaders already were casualties.

Alpha’s remaining platoon leader, Lieutenant Edwards of the second platoon, had also moved up to help. His intention was to merge his two files into one and link his unit with the right flank of the first platoon. On the way his troops started receiving fire from both sides, left and right, with the heaviest fire now coming from the left flank. It was becoming clear that the Viet Cong had Alpha enclosed on three sides. Edwards was pinned down by tree snipers, then took machine-gun fire from the front. He had brought up a machine-gun team of his own, but the M-60 quickly broke. A grenadier came on line to support, but the cocking lever on his M-79 “got out of position somehow and couldn’t be fired.” Most of Edwards’s men were twenty meters behind him, virtually out of sight. His firepower situation was deteriorating rapidly—broken machine gun, broken grenade launcher, and soon two M-16s were rendered useless by jammed bullets. All Edwards and his party had left were “one M-16 that worked, one grenade, a knife, and a .45-caliber pistol.”

Privates Costello and Hinger, the last two men in Edwards’s right file, had responded swiftly to the action at the front. Doc Hinger spotted movement in the trees at the exact moment that Michael Arias and Willie Johnson noticed it further to the front, and pointed it out to Costello, who aimed his M-79 at the treetops and lobbed a few grenades in that direction. The movement stopped. A call for medics could be heard in the distance, and with that Hinger scooted forward. Costello asked his squad leader if he should follow the medic forward and give him cover.

Do it,

came the reply, but by the time Costello turned around, Hinger was at least fifteen yards in front and lost from sight.

Dodging sniper fire, moving toward the “Medic!” shouts, Hinger made his way to George and the others wounded by the claymore blast. He began working on the first man he encountered, a private who had two massive tissue wounds, one on the leg, another on the elbow. Top Valdez was there, trying to organize the company amid the chaos. Ernie Buentiempo was nearby. After his ominous morning vibes, Goodtimes was already without his radio, which he had thrown off, and his M-16 was jammed by blood. George, barely functioning, struggled to get on the battalion net again with Terry Allen, giving him a situation report. Allen wanted a body count. George thought it was an odd time to ask for a body count. It was hard enough for him to give a reasonably accurate accounting of his own men. He had Alpha soldiers still fifty meters to the front of him, he reported, and about ten casualties in his vicinity, five of whom had to be carried. And he was still receiving fire. Allen told him to mark his position with smoke and move back. They would bring in the artillery. Breaking contact was slow, George told Allen. After that he could hear no more.

Hinger moved from one wounded man to the next. The artillery forward observer, Lieutenant Kay, was a mess: his face bloody, his leg mashed, a big chunk gone from his wrist, two gashes in his shoulder. As Hinger worked on him, the fire was so heavy that he “could almost taste the cordite.” He had tunnel vision now, the commotion around him blocked out, concentrating only on what was in front of him. Someone had taken his M-16, or he had given it away, he could not remember and it didn’t matter. Weapons were moving from one soldier to another and being left and recovered. He took Lieutenant Kay’s .45 and a clip of ammo and moved on to another soldier wounded in the kneecap. He heard someone yell, “Fall back! Fall back!” but it barely registered and he could not leave a wounded man. Riflemen Paul Fitzgerald and Olin Hargrove, along with Private first class James C. Jones, an aide to Lieutenant Kay, stayed with Hinger while the others pulled back.

Jones emptied the ammunition belt for his .45, then picked up the M-16 of a fallen soldier and fired until it jammed, and finally grabbed a discarded grenade launcher. He saw bushes moving and flashes from rifles but never spotted a single enemy soldier, though he knew they were all around. When he tried to rise up, an AK-47 shot the strap off his radio. His boss, Lieutenant Kay, was unable to call in the fire missions, so Jones would do it himself, even though he was “too scared to think clearly.” He made contact with the First Division’s artillery batteries at Caisson V, who fired 105-millimeter shells within fifty meters of his location.

Costello had been looking for Doc Hinger. As he moved toward Alpha’s front, the gunfight reminded him of “an extraordinarily good fireworks show.” Time was distorted; a minute seemed like an hour. Men were returning fire, but in the distance behind him he could hear periodic shouts of “Hold your fire! Cease fire!” Were they shooting their own men? Toward the front he was pinned to the jungle floor, hugging the ground, pressing down, anything to get a millimeter lower, his head sideways with the big steel helmet sticking up. There was no brush to cover him, only dirt and smoke. He heard rounds go overhead and felt dizzy, certain one would hit. From the sound he determined that the VC were using a big, .50-caliber machine gun, more of a

boom-boom

than a

brrrr.

He looked down and saw ants crawling on his arm. They were biting him, and he knew from experience that it should hurt, but his adrenaline was running so strong that he said to himself,

I can’t feel these suckers.

From nearby came a yell for help. He looked over at a wounded soldier. The man’s insides had come out, hanging there, suspended. Costello’s first instinct was to stuff them in, but from training films he remembered that was wrong. Cover them and apply pressure, he thought to himself, and that is what he did.

Another explosion went off behind him. Costello felt a shrapnel sting in his back. He could do no more for the wounded soldier, who was going into shock and probably dying. Try as he might, he could not call up the man’s name. He remembered that the guy had a candy-apple-red ’62 Chevy that he was proud of and a young wife he loved very much and that he didn’t care for Costello at all and Costello wished that he had. With bullets zinging overhead, there was the young grenadier, taking one last look at a dying comrade and thinking strangely,

I wish we had been nicer to each other.

In the din he could hear Top Valdez yelling, “Fall back! Fall back!”

Valdez, in command of Alpha now, had radioed Allen with another situation report. Move north, Allen had told him. He was calling in the artillery. Valdez and the soldiers with him moved seven wounded men north and east about seventy meters and formed a makeshift assembly area. He had Captain George there, and Lieutenant Kay. There was Sergeant Pipkin, who had been shot in the leg as he tried to move the first platoon’s left file over toward Gribble’s decimated right squad. Specialist 4 Carl Woodard, a squad leader at age nineteen, brought his men from the second platoon over to provide security on the right flank. Pipkin’s radiotelephone operator, Michael Arias, and rifleman Fitzgerald came stumbling back carrying a wounded comrade, Charles Morrisette. Arias had tried to get two other men to help carry Morrisette, but they were taking cover behind a shrub, pinned down by machine-gun fire; they waited for a lull in the shooting before they too crawled back. “Come to the fire!” Valdez shouted, shooting his .45 twice into the air.