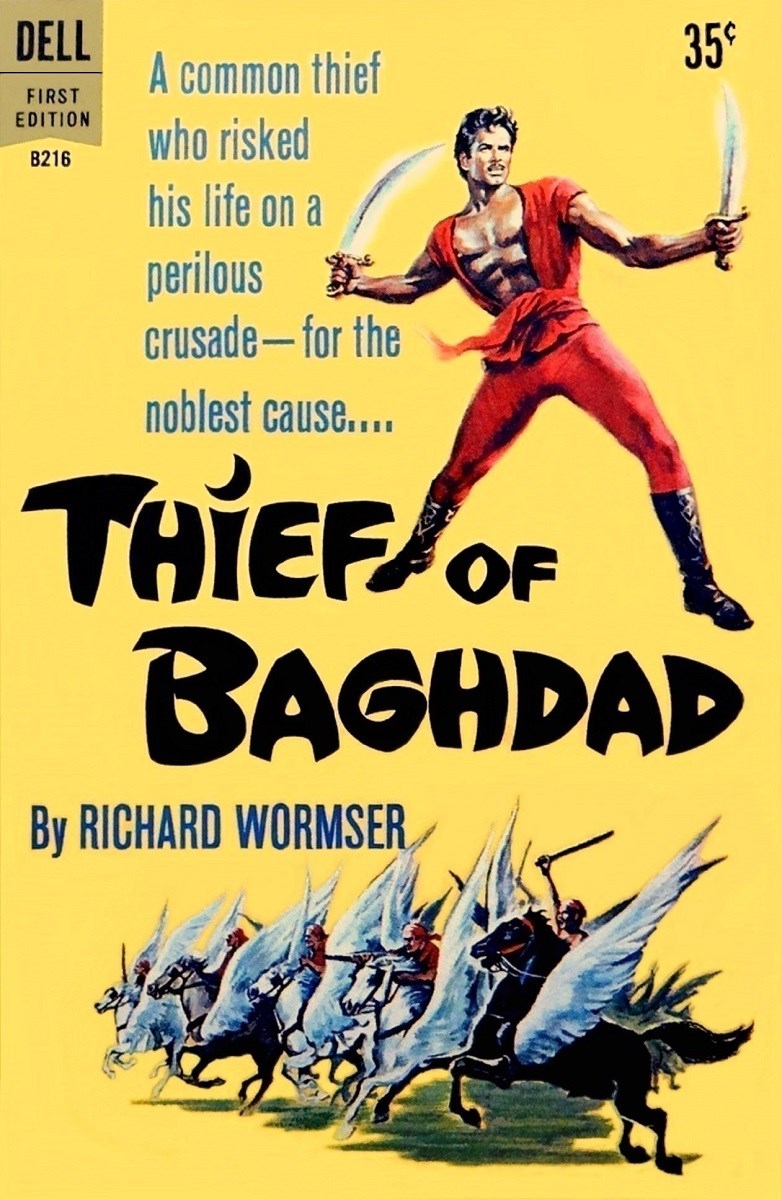

Thief of Baghdad

Authors: Richard Wormser

The Quest For The Blue Rose

And it was declared throughout the kingdom that whosoever passed through the trials of The Seven Gates and returned triumphant with a lone, blue rose would be hailed Sultan of all Baghdad and would receive in marriage the hand of fair Princess Amina.

Unthinkable that a thief, the lowliest of men, should offer his sword and his life on this perilous crusade. A crusade blocked at every turn by dangers of raging flames, invisible beasts and hooded, faceless men.

Unthinkable that even the bravest would survive to tell the thrilling tale—and yet,

one

man did!

THEIR WORLD SPUN

IN A UNIVERSE OF

MYSTERY,

ADVENTURE,

ROMANCE—

KARIM:

The brave and handsome one whose trade was stealing—but for a worthy cause . . .AMINA:

The fair princess, held captive in her own palace . . .PRINCE OSMAN:

He came from afar to claim a kingdom and a woman who loved another . . .GHAMEL:

Shrewd adviser to the meek Sultan—his power was strong . . . and treacherous . . .KADEEJAH:

The enchantress whose touch turned men to stone . . .And an old man with strange powers—without whom this story could not be told.

Published by

DELL PUBLISHING CO., INC.

750 Third Avenue

New York 17, N.Y.

©

Copyright, 1961, by Embassy International Corporation

Dell First Edition

®

TM 641409, Dell Publishing Co., Inc.

All rights reserved

Cover illustration by George Gross

This is a work of fiction and all characters and events in the story are fictional, and any resemblance to real persons is purely coincidental.

First printing—August, 1961

Printed in U.S.A.

1

M

y name is Abu Hastin, and I am a jinni; some call us djinns, and genies and other things. I much prefer being called a genius, but people seldom oblige me.

There’s more misunderstanding about us than there is about anybody, including women. I mean, we’re often supposed to be infallible, all-powerful, and immortal; we’re none of these things. What we are is hard-working, long-lived—I’m seven hundred and sixty-two—and under very strict discipline. Also, we come both male and female, Allah be thanked.

I’m the Jinni of Baghdad, at the moment, have been for several hundred years. And I remember one time when being the Jinni of Baghdad was no fun.

We had a big meeting of jinns at Kaf Mountain, which is our world headquarters, where we get together every so often to listen to the spirit of the great Suleyman, and for other reasons. I already said we come both male and female, but since there’s only one jinni to a jinnisdiction, it gets lonely. I always look forward to our conventions.

The trouble was that the Sultan of Baghdad was an old fool. He was probably the silliest sultan east of the Jordan and south of the Mediterranean, which just about covers all the sultan territory there is.

So every time I’d invite a lady jinni to smoke a bit of hashish with me, preliminary to working up a personal burn, she’d say: “Oh, you’re the lazy jinni, with a fool for a sultan. Let me tell you, I wouldn’t put up with a thing like that for five Mesopotamian minutes. What I’d do—”

And instead of intimacy, I’d get instructions. Lady jinns can be very long-winded when they’re right and you’re wrong. Especially the Lady Jinni of the Rocky Sands, who, to me, is the most beautiful jinni who ever landed on Mount Kaf.

I returned to Baghdad determined to do something about the sultanate. The only thing I could think of doing was to replace the fool with a wise man. I don’t mean smart; I mean wise. I wanted someone who had brains, courage, compassion, good looks, honesty and an active, handsome body.

You don’t find something like that in just any camel yard.

I was hungry after my long flight back from Kaf; hungry for some Baghdad

rahat lakhoum,

which is the best in the world. I filled the pocket of my robe and headed for the palace; I don’t know why. Maybe I hoped that the Sultan had grown a new head while I was away, or maybe I wanted to look over the courtiers and see if any of them had the qualifications I needed.

My disguise at the time was that of an old man, not too rich, and not too smart looking. In fact, I modeled my appearance on that of the Sultan’s grandfather, Achim I, whose picture was all over the city.

He

had been a sultan! It was an honor and a pleasure to be Jinni of Baghdad in his day.

Something was going on at the palace; I didn’t know what, I was out of touch. A mob packed the big square, and up on the edge of the lowest roof of the place Ghamal, the Grand Vizier, was about to make a speech.

Ah, it was good to be back in Baghdad, foolish Sultan or no. These were my people, these were my camels, these were even my pariah dogs, snapping at people’s heels and fighting in the gutter.

The sound of the water vendors and the almond sellers and the rug merchants crying their bargains was as beautiful to me as the singing of bulbul birds on a spring night. It was a spring day, now, and the girls of Baghdad were wearing their gauziest clothes, with nothing really well covered except their faces, as becomes modest Arabian maidens.

Arabian girls are built just like lady jinns, but I am, unfortunately, forbidden to have anything to do with them. The life of a jinni has its drawbacks, especially in spring.

Now Ghamal was getting ready to read his proclamation; the palace servants had swept the place, and put a fresh Persian carpet down on it, and were escorting him to stand there, where his vizierly feet would not be corrupted by a speck of common dust.

This Ghamal was a fellow I didn’t know too much about. He’d come up in the Sultan Service very fast; just a couple of years ago he’d been a deputy tax collector way out in the outskirts of Samarra. I would have liked to have dematerialized and gone up for a closer look at his face—maybe he was my man—but it would have startled the crowd, and stolen the show away from him, which is conduct unbecoming a gentleman and a jinni.

A scribe handed Ghamal a rolled-up scroll, and he shook it loose with an air; he’d make an imposing-looking Sultan, he knew all the tricks. Then he cleared his throat, and gave the old traditional: “Hear, O people of Baghdad.”

He waited while the people got quiet. Some of the pariahs even stopped yapping, curious about what would make Baghdadians stop talking. Two or three cutpurses made their expenses for the day, while all eyes were on Ghamal.

“Hear, O people,” Ghamal said again, “the message of your lord and master, Abdir Bajazeth, Sultan of Baghdad, Lord of Samarkand, Ruler of Samarra, Emperor of Iraq-Ajeemi!”

“And an old fool,” a man near me muttered. But not loud enough for the ears of any secret police who might be mingling with the crowd; I wouldn’t have heard him if I didn’t have jinni-hearing.

“We, your Sultan,” Ghamal boomed on, “decree that this day, the fifth of the seventh moon, in the fiftieth year of our reign—”

Really, I had been delinquent in my duties, to let this go on that long.

“—be blessed and remembered as a day of universal rejoicing.”

Then I was sorry I’d bought the candy, because by tradition in Baghdad, a day of universal rejoicing called for the throwing of free

rahat lakhoum

to the crowds. But money means very little to me.

The palace guards were coming forward, up on the terrace, and handing Ghamal a little bag of sweetmeats to throw over the wall, to start the rejoicing. The people down in the square started murmuring happily. I ate a couple of pieces of my candy quickly, ready to fill my pockets again at the public expense.

Ghamal reached into the bag and made his first toss. When the bag was empty, again according to tradition, the servants and guards would take over, heaving tons of our local confection to the people.

Ghamal made a nice pitch; one of the sweetmeats came right into my hands. I took a bite of the free candy; and then I was spitting, and so were all the people around me who had been unlucky enough to catch a sweetmeat.

Rahat lakhoum!

Baghdad

rahat lakhoum!

This stuff wasn’t fit to give to the hungriest beggar in Az Zubair. It was a disgrace to the finest city in all Arabia.

The guards threw three baskets of the junk out to us, but nobody bothered to pick the so-called sweetmeats up. Even some of the pariah dogs, though not all, were scorning it.

The Baghdadians who had tasted the first throw were spitting even more freely than most Baghdadians, and my people are the finest spitters in the world.

Ghamal, the Grand Vizier, was a penny-pinching rat, a thief and a scoundrel. When I put my new sultan in, he’d be under instructions to get rid of Ghamal slowly, painfully and permanently. You can’t fool with my

rahat lakhoum

and get away with it, even if I’m widely known as an extraordinarily patient jinni.

Old sugar-stealer was proclaiming some more. He held the scroll in front of his disgusting face and boomed: “Tonight, from the faraway kingdom of Mossul, Prince Osman comes to ask for the hand of our dearly beloved and only daughter, the Princess Amina.”

The people of Baghdad were supposed to cheer at this point, but you don’t cheer with a bad taste in your mouth. A few men yelled, a sure giveaway that they were the Vizier’s undercover men in the crowd.

But that Ghamal acted as though everything was going smooth as fresh date juice. “We, your Sultan, order therefore that our noble guest—”

Something was happening up on the terrace. A young man, not well dressed, was sneaking up behind the canopy that kept Ghamal’s ignoble head safe from our Arabian sun. The guards didn’t notice; they were too busy throwing out those confections of mixed sawdust and camel dung. I smiled to see that they didn’t, as was their custom, sneak any into their own mouths between pitches.

This was interesting; full of suspense. If that young fellow intended to assassinate Vizier Ghamal, I had better get ready to materialize up there, to help him get away. But he didn’t have a weapon in his hand. Maybe he was going to make Ghamal eat one of his own candy-shaped pieces of filth. That I would enjoy.