Read Think Like an Egyptian Online

Authors: Barry Kemp

Think Like an Egyptian (37 page)

An impure person was barred from sacred spaces including chapels attached to private tombs. Curses in tombs were directed at impurity rather than at robbery. “As for any man who enters this tomb unclean, I shall seize him by the neck like a bird, and he will be judged for it by the great god,” states Harkhuf in his tomb chapel at Elephantine. Modern visitors to Egyptian tombs who worry about the curse of the Pharaohs should bear this in mind, and prepare themselves with a course of natron ingestion starting ten days beforehand.

93.

TO BE DIVINE

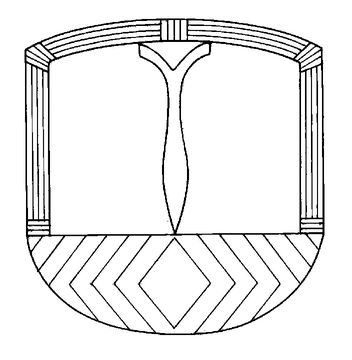

The sign is an upright pole bound with strips of what is perhaps cloth, the ends of which emerge at the top as a group of streamers. It is not an image of anything obviously recognizable, nor related to any religious cult, although the tall flagpoles and streamers that stood against the entrances to Egyptian temples were perhaps modeled on it. The hieroglyph seems to depict something hidden yet designed to catch the attention—something tangible that triggered belief in a hidden world of unearthly power. It wrote the word

n

n

t

ry

(

netjeri

)

,

“to be divine,” and hence

n

n

t

r,

“god,” and

n

n

t

rt,

“goddess.”

n

nt

ry

(

netjeri

)

,

“to be divine,” and hence

n

nt

r,

“god,” and

n

nt

rt,

“goddess.”

Divinity was found in kings, falcons, temple buildings, sacred mounds, pools of water, and, of course, gods and goddesses and their “spirits” and “souls.” The Egyptians sometimes interpreted the sensation that lonely desert peaks provoked as a manifestation of the goddess Hathor (see no. 12, “Tree,” and no. 67, “Sistrum”). The “Peak of the West” in the cliffs above the necropolis at Thebes was called “Meret-seger,” “she who loves silence.” For the most part, however, the Egyptians built temples to experience a divine presence.

The central focus of a temple was the statue of the presiding deity (see no. 96, “Statue”). It normally stood in a shrine at the back of the building, a place of little light, reached by priests through a series of wooden doors that were ritually opened and closed. The statue was kept clean and pure through libations of water, was draped with linen, surrounded with the smell of incense, and presented with portions of food and drink as “offerings.” The spirit of the god that dwelled in the statue also inhabited a portable image, which was paraded outside the temple and seen by the general population. From at least the New Kingdom onward statues communicated messages by means of an “oracle” (see no. 97, “Wonder”). Some were set up in more accessible shrines on the edge of the temple enclosure and could “hear prayers” from the local populace, though in a carefully managed atmosphere.

Divinity extended to the statues of leading citizens, the provincial governors, mayors, and high officials who had local connections. In a small number of cases the cults of these people assumed a status indistinguishable from that of local gods and goddesses: evidence is found on tombstones where Egyptians asked them to intercede to ensure a regular supply of offerings. A vizier buried at the provincial town of Edfu was invoked centuries after his death. More striking still was the governor of Elephantine, Hekaib, who lived in the late Old Kingdom. Two centuries later the local mayors set up a shrine containing his statue in the middle of the town. As the years passed, each mayor added his own shrine and statue, as did a few kings. Hekaib’s shrine, with its own calendar of festivals, became the principal religious center for Elephantine for the next two and a half centuries, eclipsing as far as we can see the local cult of Khnum, the creator-god, and his consort, the goddess Satis.

It was not necessary to visit a temple to make contact with the gods. Their blessings could be invoked in private letters, and their presence could be felt in lonely settings. The Egyptian hero Sinuhe, in exile in Palestine, makes the appeal: “Whichever god decreed this flight, have mercy, bring me home!” When trouble arose many avenues were open for assistance: places set aside at the local shrine, a doctor or like person who had knowledge of demons good and bad, and one’s own dead relatives at their tombs (one could deposit there a letter addressed to the dead asking for or even demanding assistance).

Yet it would be a mistake to think that the Egyptians were more religious than other peoples. The awe toward the divine that they felt in special places did not necessarily persist in familiar surroundings. It was then safe to imagine the gods as fallible, and even to ridicule them. A long and beautifully written papyrus found in the private library of the widow Naunakht at Deir el-Medina retells the conflict between Horus and Seth as a burlesque in which even the greatest of the gods look foolish. Ambivalence extended to the dead. Tomb robbery was as old as careful burial, and songs and poems referred to the difficulty of gaining immortality through tomb-building and to the uncertain fate of the dead. There was a strand in Egyptian thinking that kept religion in perspective.

94.

SACRED

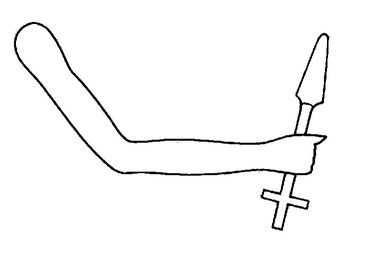

The hieroglyph shows an arm brandishing what looks like a piece of branch, which itself has been stylized as a particular kind of scepter. It appears only in a word with the basic meaning “to clear” or “to separate.” From this developed the particular nuance of “sacred,” something set aside and segregated from all else. It applied to temple buildings, tracts of land (including the land of Punt, which provided incense), the horizon, and the images of kings and gods and their names.

Sacredness wielded considerable power in the Egyptian mind and was taken very seriously. During the festival of Osiris at Abydos, a procession bore the sacred barque of Osiris from the temple across the desert toward his tomb and, along the route, reenacted an attack by the enemies of Osiris. The tract of ground that the procession crossed was marked out by tall granite slabs (stelae) on which was written a decree for “the protection of the sacred ground south of Abydos ... forbidding anyone to trespass upon this sacred ground.” The penalty for disobedience was fierce: “As for anyone who shall be found within these stelae, except for a priest about his duties, he shall be burnt.”

A secure way of separating the sacred from the profane was by building a wall (see no. 33). Egyptian temples, even when quite small, were customarily shut off from the outside world by a thick wall of sun-dried mud-bricks. In the New Kingdom and later, these walls were fashioned to look as though they belonged to a fortress, with a line of battlements along the top parapet. The temple enclosure was shut to the outside world.

The Egyptian distinction between the sacred and the profane was not as absolute as we might expect, however. Although all property of gods was sacred, often that property included all the characteristics of profane daily experience. Temple enclosures could contain storerooms, kitchens, kilns, and houses, along with craftsmen, administrators, and porters. There were times when the encroachment offended those in charge and purification became necessary. The priest of Sais, Udjahor-resenet, in the time of the Persian occupation of Egypt (525 BC), obtained permission to “expel all the foreigners [who] dwelled in the temple of Neith, to demolish all their houses and all their unclean things which were in this temple.” Similarly the high priest of Amun-Ra at Karnak, Menkheperra of the 21st Dynasty, recorded how he had removed the houses of Egyptian people installed in the court of the “domain of Amun.” In this case we can see that what he did was less thorough than the text implies. Archaeological excavation has revealed that houses lay at this time inside the main temple enclosure and remained there for a long time afterward. Perhaps what he removed were houses touching the actual stone fabric of the temple. Egyptian religion, despite its impressive scale and elaborate organization, faced inevitable compromises.

95.

FESTIVAL

The Egyptian year was broken up by many festivals and religious holidays. The Mayor of El-Kab, Paheri, hoped for offerings in his tomb not only every day, but in particular “on the monthly feast, the sixth-day feast, the half-monthly feast, the great procession, the rising of [the star] Sirius, the

Wag

-feast, the Thoth-feast, the first-birth feast, the birth of Isis, the procession of Min, [and] the procession of the

sem-

priest.” One distinctive festival developed out of the Egyptian calendar. The year was divided into 12 months of 30 days. This left five days over, called “the five days extra to the year” and formed part of the temple calendar of feasts.

Wag

-feast, the Thoth-feast, the first-birth feast, the birth of Isis, the procession of Min, [and] the procession of the

sem-

priest.” One distinctive festival developed out of the Egyptian calendar. The year was divided into 12 months of 30 days. This left five days over, called “the five days extra to the year” and formed part of the temple calendar of feasts.

Other books

On the Right Side of a Dream by Sheila Williams

Lt. Leary, Commanding by David Drake

Spinning the Globe by Ben Green

Tales of Lust and Magic by Silver, Layla

A Proper Mistress by Shannon Donnelly

The Devil's Mirror by Russell, Ray

Pulse - Part Four (The Pulse Series) by Deborah Bladon

Cotton's Law (9781101553848) by Dunlap, Phil

Finding Home by Weger, Jackie

Hummingbird by Nathan L. Flamank