Third Degree

Authors: Julie Cross

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #Women's Fiction, #Contemporary Women, #Romance, #Contemporary, #New Adult & College, #Contemporary Fiction

Third Degree

is a work of fiction. Names, places, and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

A Flirt eBook Original

Copyright © 2014 by Julie Cross

Excerpt from

Shredded

by Tracy Wolff copyright © 2014 by Tracy Deebs-Elkeneney

All Rights Reserved.

Published in the United States by Flirt, an imprint of Random House, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

F

LIRT

and the F

LIRT

colophon are trademarks of Random House LLC.

eBook ISBN 978-0-553-39034-6

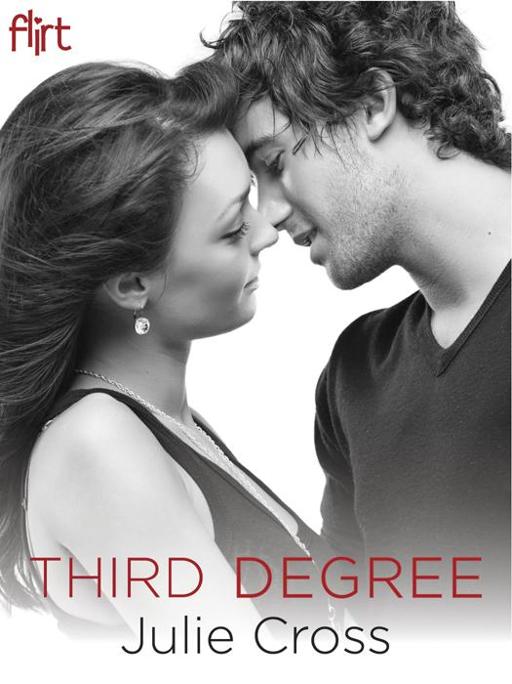

Cover photograph: © Lorand Geiner/Getty Images

Author photograph: © Christian Doellner

This book contains an excerpt from the forthcoming book

Shredded

by Tracy Wolff. This excerpt has been set for this edition only and may not reflect the final content of the forthcoming edition.

Cover design: Susan Schultz

Cover photograph: © Lorand Gelner/Getty Images

v3.1

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Excerpt from

Shredded

Chapter 1

@IsabelJenkinsMD:

Got another medical myth to debunk for you today.

@IsabelJenkinsMD:

Myth—humans only use 10% of our brains.

@IsabelJenkinsMD:

This very inaccurate theory is most likely the result of some pseudo-psychologist from 1900 trying to employ motivational tactics.

@IsabelJenkinsMD:

In his/her patients on the order of “it’s physically impossible for bees to fly” so let’s all be inspired to do the impossible.

@IsabelJenkinsMD:

The bee flight issue has recently been clarified and there is now a scientific explanation.

“It’s diabetes.”

Justin taps his fingers on the receptionist’s desk outside the lab. “The kid’s been in the ER five minutes and you have a diagnosis? Bullshit.”

I flash Justin a grin so I can keep from grinding my teeth. I don’t hate him. That would require a level of caring that we never reached. I loathe him. Him and his smaller-than-average penis. “He’s been here at least an hour, especially if you factor in the time in the waiting room.”

“Why do you do that?” Justin snaps. “You know what I meant by five minutes. I know you did. You’re stalling because you don’t really have specific reasons to believe it’s diabetes. You’ve done some freakish statistics in your head and odds are in favor of diabetes.”

Idiot

. “And this is exactly why physical intimacy is all we were ever good at.”

Justin’s eyebrows lift up. “Physical intimacy is all

you

were good at, Isabel.”

Okay, so that stings. Not because I care what that stupid prodigy thinks (though, if we’re getting technical, I started med school much younger than he did), but more that I’m secretly petrified he’s right and the label will haunt me wherever I go. But the intern mantra, “Show no fear,” plays in my head a few times, giving me a surge of confidence. “Oh, so you admit that I’m good in bed?”

A flicker of regret flashes across his face, but like me, he knows the mantra. “I don’t recall any beds being involved. Floors, yes. A couple of walls.”

A lab tech walks toward the front desk and stops when he sees us eagerly waiting. He

snorts with laughter. “I bet the two of you would fork over some serious cash for the contents of this folder.”

I snap my fingers. “Hand it over. Now.”

“Ignore her, she has no people skills,” Justin says before turning to me, calm as anything. “A hundred bucks, the next three enemas, and a round of kindergarten booster shots on the line. Still going with diabetes?”

He should know better than to doubt me when it involves giving shots to kicking, screaming kindergarteners in the free clinic. “Yes. Are you still going with lower intestinal bacterial infection?”

The folder lands in Justin’s hand, but he continues to stare at me, not opening it. He plays this part of our game so well. It drives me nuts. I used to think it was sexy, but now I can’t stand him. Or his penis. The guy didn’t even start med school until he was nineteen. Some prodigy.

“There’s no family history of diabetes. The kid’s only been sick for five days,” Justin repeats, as if I don’t remember details of a patient exam that happened minutes ago. “He was in fucking Mexico last week!”

“Enough,” the lady behind the desk hisses at us. “If Dr. Rinehart knew you were betting money on a patient’s diagnosis, you’d both be written up.”

Everyone knows Justin and I play this game, but getting caught doing it by our boss is an entirely different thing. I lower my voice and snatch the folder from his hands. “Yeah, a posh all-inclusive resort where everything is imported from the States.”

I open the folder, scan the blood work numbers, and keep my face completely under control as I close it and pass it to Justin before walking off. I’m all the way to the ER doors before he comes jogging up behind me, the folder tucked under his arm. He pounds his palm against the button providing access to the ER.

“I was right, wasn’t I?” he says. “You did some statistics thing in your head.”

“Nope.”

“We both know you didn’t go with a gut feeling, because Isabel Jenkins only diagnoses with evidence.”

I stop in the middle of the hallway and spin around to face him. “There might not be a family history of diabetes, but there is a family history of B-cell autoimmunity.”

His face falls so fast, I almost feel guilty.

Almost

. “The uncle with lupus … shit, I didn’t even—”

“And the paternal grandfather with rheumatoid arthritis. And then on top of that, did you smell his breath? A kid who’s been barfing his guts out and not eating shouldn’t have fruity-smelling breath.” I pat him on the shoulder. “It’s all right. I’m sure those questions weren’t on the intern exam. You probably did just fine. The chief is going to have all kinds of residency

options for you, what with all the county hospitals in major cities desperate for subpar surgeons who can perform operations for half the cost of those fancy private hospitals like Johns Hopkins.”

Okay, that was one step too far. It’s so hard to hold back the trash talk when Justin and I are in competition mode. He pushes me and I push him. It seems horrible, but we’re both better doctors because of our head-to-head battles. But maybe we do need to seek out a healthier method of increasing drive. That’s a goal I can add to my list for when I’m a resident at Johns Hopkins.

Justin shoves my hand off his shoulder. “Go screw yourself.”

I want to be pissed at Justin for not taking his loss like a man and being an idiot, but at the same time,

I’m

not an idiot. Which means I’m aware of how difficult I can be. If I could figure out what to do about it, I might change, because being the difficult one does get lonely and often comes with large doses of guilt. Which is probably how I ended up naked in a locked on-call room with said idiot (also naked).

After delivering the orders for treatment meds to the nurses’ station, we both have to walk together into the patient’s ER room, where our boss is waiting for lab results.

“It’s diabetes,” I say before she can ask.

Dr. Rinehart turns around and eyes me and Justin. Justin’s busy studying his shoes like a patient just bled out on top of them.

Sore loser

.

“Dr. Jenkins,” Rinehart says to me. “You have the lab results?” Her eyes flit in the direction of the fifteen-year-old kid in the hospital bed and his mom seated in the chair in the corner of the room.

I glance at them for a split second and then focus on my boss. “Yes, ma’am. It’s type one diabetes—”

“Diabetes?” the mom says, then she points at Justin. “He said it was probably food poisoning.”

“He was wrong.” The grin sneaks up on me for a second, but I smooth my mouth into a straight line again.

“Wait.” The kid pulls himself to a sitting position. “I have to, like, give myself shots and stuff? I hate needles.”

“Insulin,” I say. “You’ll need to regulate your body’s blood sugar levels.”

“For how long?” the kid and the mom both ask.

I stare at them blankly.

Is that a real question, or is she being sarcastic?

“Forever.”

The mom immediately bursts into tears. The kid snatches his cup of water and throws it across the room, splashing the clean white walls.

Dr. Rinehart opens her mouth to speak, her eyes narrowing at me. “Dr. Jenkins, perhaps

you should backtrack a little, start with how you came to this diagnosis.”

I take a good five minutes to go through each symptom presented and how it connects to the diagnosis, and then I move on to the family history connection. By the time I finish my report, Dr. Rinehart is rubbing her temples and a nurse is hooking up the insulin pump I ordered for the patient right before coming in here to deliver the news.

“I’m not doing it!” the kid shouts at the nurse, fighting her, not allowing another needle to enter his body. “This is fucking bullshit! None of you know what the hell you’re doing!”

My gaze sweeps the room, taking everything in—the sobbing mom, the adolescent with the flailing arms. Jesus Christ, these people are dramatic. “He’s going to be okay, you know?”

The mom points at her kid. “Does this look like okay to you? He’s sick, and you’re telling me he’s gonna be sick forever. We came here so you could make him better.”

“He’s alive,” I point out. “He’s not dying. Diabetes is manageable.”

“Get her out of here,” the mom shouts to Rinehart. “I don’t want her anywhere near my son.”

I expect Rinehart to defend me, but instead she turns to Justin. “Dr. Martin, I’d like you to get the patient admitted to the pediatric floor, talk the family through the next few steps and let them know what they can expect to see with their son’s health, and then call up our support group specialist.”

“Yes, Dr. Rinehart,” Justin says.

I clamp my teeth together, my jaw tense with words of protest. As soon as we’re outside the room, heading down the hall, my mouth opens again. “You’re leaving them in Justin’s hands? He completely missed the family history and odor in the kid’s mouth.”

“I realize that,” Rinehart says. “But Dr. Martin is only human. He missed something and you caught it. The patient will receive appropriate treatment. His case is nonsurgical, so after he’s admitted we’re all done. Besides, the blood work would have provided the answers we needed regardless of whatever game the two of you were playing before we got the results.”

Dr. Rinehart was the lucky doctor assigned to supervise the youngest medical interns in the history of the University of Chicago Medical Center. And I have to admit, she does have unending patience. It can’t be an easy job.