Third Reich Victorious (24 page)

On July 5 the RAF was still able to mobilize a strong screen of defensive fighters, operating comfortably within their own airspace almost directly above their base airfields. They exacted a heavy toll on the lumbering enemy bombers, with claims amounting to eighteen definites and eleven possibles; although five of their own number were shot down by the ever-dangerous Messerschmitt 109s. This stalwart defense could not be maintained for long, however, since the RAF was already reviewing the vulnerability of its landing grounds in the same way the navy had already looked at its port facilities. An air redeployment to the canal zone and Palestine was initiated at 1330, although much of its transport rapidly became mired in the general confusion of traffic and refugees, with the overall result that many sorties were lost.

As for the army, July 5 was a day of which the New Zealanders would be justly proud, since they doggedly beat off a series of ferocious attempts to reduce their two boxes. Farther to the rear, events went much less well. Gott’s 8th Army HQ had been disrupted by shelling at dusk on the July 4 and hastily removed itself farther to the east, losing contact with many of its vehicles in the dark. It was not until 0300 on Sunday, July 5

6

that Gott was able to issue his next set of army orders, which thus arrived too late for units to launch counterattacks at dawn. In essence he wanted to concentrate all available armor, mobile forces, and reserve columns against the DAK on Alam el Haifa ridge, but when Rommel launched his own attack first, the British columns were committed piecemeal and defeated in detail. By noon the Germans were firmly astride the coast road well to the rear of El Imayid, where they found extensive supply dumps. Yet again their fuel shortage was solved in the nick of time courtesy of the British Empire. They also found a large mass of invaluable motor transport, as well as a large park of partially repaired tanks that the tireless DAK maintenance teams would quickly restore to fighting order.

All allied formations farther to the west were now effectively cut off, and faced with an unpalatable choice between surrender and attempting to slip through the lines of their besiegers. In every case the second option was preferred, and a series of fighting breakouts was launched soon after darkness fell, though in many cases the attempt was unsuccessful. Many confused battles were fought during the night, with dawn on July 6 revealing that all the infantry boxes had been evacuated, but some 8,000 South Africans and New Zealanders had passed into captivity. The remainder were scattered all over the desert and moving in small groups, either on foot or on wheels, in the same general direction as the victorious German and Italian columns. At the head of the pack rode Rommel himself, now totally committed to a flat-out race to Alexandria, and safe in the knowledge that the RAF could no longer distinguish his ragged dust-caked vehicles from those of the 8th Army. All were mixed together in an incoherent mass that normally seemed to be more worried by traffic congestion than with maintaining hostilities.

The first truckloads of Panzergrenadiers entered the suburbs of Alexandria at 1100, but encountered little organized opposition apart from what even the official history would call Brigadier A.H.L. Godfrey’s “motley force” around Amiriya. During the afternoon the Germans pushed on into the city center, with a few sharp firefights but more of a sullen acceptance of defeat by service personnel who had never thought of themselves as front-line troops, let alone as cannon fodder. Beyond those there was an equally resigned acceptance among the local population, meticulously schooled by centuries of experience, toward whichever rudely invading army happened to be passing through at the time. Meanwhile, Gott was desperately trying to gather a coherent fighting force farther inland, although he was seriously hampered by the catastrophic dispersion and confusion throughout his command. As for Alexander, he had returned to GHQ in Cairo to cope with a contingency that until then he had tried to deny was even a possibility.

Apart from Gott’s remnants, what could still be rescued, now that Alexandria had fallen into enemy hands? There was actually a substantial reserve scattered around the area, with its more battleworthy elements forming “Delta Force,” commanded by the same Gen. Holmes who had failed to defend Mersa Matruh. Perhaps his most solid bastion was formed by General Sir Leslie Morshead’s 9th Australian Division blocking the approaches to Cairo—ably reinforced by such distinguished warrior bands as an upgunned Greek police battalion left over from Crete, a Basuto artillery regiment, and the GHQ “Officer Cadet Training Unit,” which was delighted to be excused from lectures for the duration of the crisis. Also refitting in the same area were the 50th Division and 10th Indian Division, both of which had been badly battered at Matruh. Behind these were many more units located in various camps along the canal, especially toward its southern end where new arrivals from overseas were groggily finding their bearings after disembarkation at the port of Suez. Among the more experienced combat elements were the 2nd and 8th Armored Brigades, in the process of being composed from a number of shattered tank regiments; the 161st Indian Motor Brigade, just in from Iraq, and a skeleton the 2nd Free French Brigade Group. On paper there should have been the best part of 1,100 tanks, although only a very small percentage were in any state to fight, even if they had not already fallen into enemy hands around Alexandria.

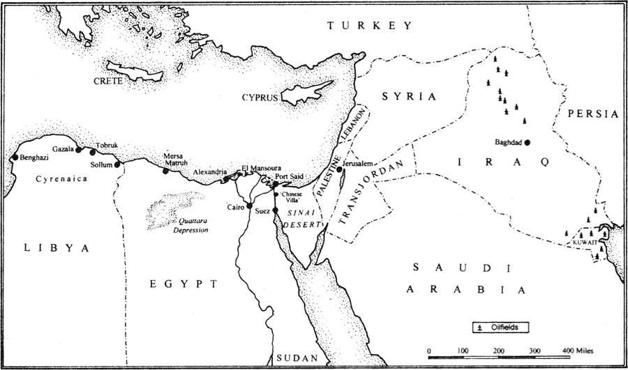

Map 8. North Africa

Rommel was also receiving reinforcements of his own, not least in the shape of captured British fuel, guns, tanks, and an esoteric variety of specialist equipments ranging from experimental mine flails to the much admired “Mammoth” armored command vehicles. Some 2,000 individual German reinforcements were airlifted in from Crete by July 5, soon to be followed by the 164th Light “Afrika” Division and then, toward the end of the month, the “Ramcke” Paratroop Brigade—which was surely as happy to have been spared the dangerous task of jumping onto Malta as Rommel was happy to add them to his own order of battle in Egypt. All these were accompanied by an even greater number of Italian reinforcements, not least the “Folgore” Parachute Division, also relieved from duty in Malta, as well as the preeminent figure of Il Duce himself.

Benito Mussolini had been hovering in Cyrenaica since June 29, complete with a handsome white horse and appropriately imperial trappings, and he now came forward to El Imayid in readiness for the final triumphal entry into Cairo. However, he quickly fell into a blazing argument with Rommel when the Desert Fox let slip that he had no intention of going to Cairo at all, but was going to let it “wither on the vine” while he pushed on eastward to Port Said. The German staff analysis was that the British had concentrated their strongest defensive position around the militarily irrelevant capital city, thereby leaving proportionally less to cover the vital high road into Asia. There would thus be no new “Battle of the Pyramids,” but a far more telling strategic thrust across the canal and then—who could tell?—onward to link hands with the victorious German armies coming through southern Russia. As always, the Italian objections were quickly overruled by reference back to Hitler, and Mussolini had to rest content with an almost triumphant parade through Alexandria, after which he took himself away to Rome in a very angry mood.

Not even Rommel, however, was ready to continue his eastward thrust after such a breathless gallop from Gazala to the Nile. He was now ready for a logistic pause to digest his prizes, gather his forces, and study his next move. In particular he needed to bring forward the infrastructure of his air force, in the hope of regaining local parity with the RAF and hence a greater level of security for the vital sea supply lanes from Italy. He also now found a need for one item that had been distinctly unnecessary in the arid wastes of the western desert—a pontoon train for crossing the branches of the Nile, and the Suez Canal itself. His engineers set about collecting small boats that could be put to this use, and won an unexpected golden bonus when they discovered a large store of British bridging material hidden amid the almost endless warren of base facilities in the region of Amiriya.

Meanwhile, General Alexander, having at last abandoned his reluctance to contemplate further retreats, ordered hasty staff studies for a double withdrawal: northeastward into Palestine, and south up the Nile toward the Sudan. A major difficulty was that the two routes were divergent and would split the army in the face of a centrally positioned enemy, but it had to be accepted that the basic geography of Egypt nevertheless made such an outcome inevitable. The truly awkward political dilemma was to know which of the two lines of retreat should be given the main priority. In the Mehemet Ali Club in Cairo the overwhelming opinion was naturally strongly in favor of concentrating maximum effort on defending Cairo, which was considered the real jewel in the crown of the British Empire in the Middle East. By contrast, in Alexander’s HQ, and beyond that in Whitehall and Downing Street, the main concern was the oilfields of Iraq. Not only was the oil vital to the British war effort, but the Axis powers were known to be suffering badly from an acute oil shortage. It would therefore not be hard to predict that the side that eventually possessed Iraq would also be the side that won the war.

Alexander believed he could fight on both fronts equally, especially since Churchill kept reminding him that he had two-thirds of a million men and “1,100 tanks” under his command, and the Axis troops in Alexandria could not have numbered many more than 10,000 men and were last seen running only the proverbial “twenty tanks.” Everyone at GHQ was confident that a solid defense on all fronts was perfectly feasible, especially since it was estimated that Rommel could not resume his advance before mid-August at the earliest. Signal intercepts revealed that his scheduled reinforcements would not all have arrived until about then, so it was assumed he would not dare to attack until they had all been fully incorporated in his force. Plans were duly made for a preemptive counterattack upon him with four armored brigades, to be launched on August 5, under the code name “Operation Locust.”

7

It was only a troublesome group of pessimistic desert veterans, led by Gott himself, who rocked the boat by pointing out how often in the past GHQ had overestimated the time Rommel needed to regroup. Alexander, who had not personally experienced those occasions, replied that optimism and belief in victory were the key requirements at this delicate phase. The preparations continued according to the GHQ timetable, regardless of Gott’s objections.

Sure enough, however, Rommel did strike first, on the night of July 27-28, in Operation Zauberteppich (“Magic Carpet”). Parties of Ramcke and Folgore paratroops took the lead, in what was the first major operational night drop of the war. They unrolled an “airborne carpet” eastward across the various waterway and branches of the Nile, similar to the one unrolled in Holland in 1940 over the Maas, Waal, and Lek. This concept involved seizing key bridges before they could be blown, or key crossing points where they had been, and then holding onto them tenaciously until a heavy spearhead of the 15th Panzer Division, with combat engineers well forward, could arrive overland and either cross directly or lay a pontoon bridge. It was judged too ambitious to attempt a drive all the way through to the Suez Canal itself, 100 miles distant, which might have been “a bridge too far.” Even without that, the operation was already very ambitious, and frankly lucky to succeed as well as it did. All key objectives were secured by the paratroops soon after dawn; the British were visibly taken by surprise; and the remainder of the airborne carpet had been fully unrolled by the evening of July 28. Then came the battle of the bridgehead (officially known as the “Battle of the Nile Delta”), as Rommel hastened to consolidate his winnings against counterattacks and also, still more important, to rush forward the main body of the DAK, now respectably rebuilt to a tank strength of 190. Almost half of the tanks were captured Matildas, Grants, and Valentines, which were the only British types considered worth running.

Meanwhile, Rommel had strengthened his defenses south and west of Alexandria with a line of Italian infantry positions stiffened by Luftwaffe antiaircraft units manning the remarkably large total of 36 British 3.7-inch antiaircraft guns that had been captured. These guns were actually ballistically superior to the equivalent German 88mm piece, but it had always been a tenet of British belief that they were best used to protect the Alexandria naval base and airfields against air attack, rather than to hunt Panzers in the desert. Now that he had captured Alexandria’s stock of 3.7s, however, Rommel was easily able to convert them for use against tank attack, in the habitual German manner.

July 29 was a day of heavy battle, but the unexpected timing, direction, and speed of the attack caught the British armor dispersed and unprepared. As so often in the past, it came in uncoordinated and piecemeal, suffering all the disadvantages of being forced into a tactical offensive after the Germans had grabbed the operational initiative. The newly arrived 23rd Armored Brigade put up a particularly disappointing performance when it attempted to attack Alexandria from the west, and fell foul of a well-organized Pakfront. The Australian infantry and artillery that tried to follow up by seizing Amiriya during the following night fared considerably better, but were eventually pinned down and forced to withdraw next morning, when the “Ariete” Armored Division threatened a counterattack. Nearer to the

schwerpunkt

around El Mansoura, some sixty miles farther to the east, better results were achieved by the 2nd and 8th Armored Brigades, supported by the Free French Brigade. They too were eventually ground down by the concentrated might of the DAK, but not without a hard fight during which Rommel twice believed he would have to retreat. As for the 1st Armored Division, it scarcely managed to engage at all, and scatological opinions over who should take the blame varied colorfully between “badly trained junior officers,” Lumsden, Gott, and even Alexander himself.