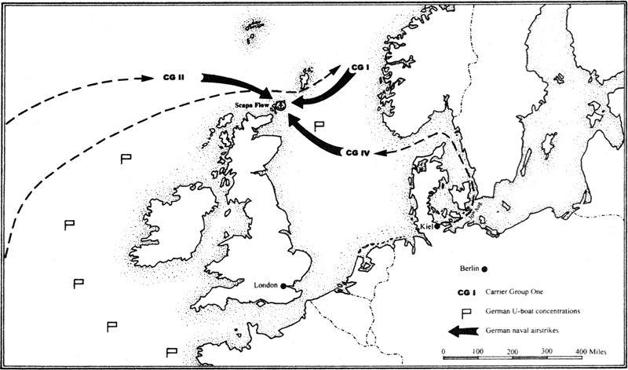

Third Reich Victorious (5 page)

By the evening of August 31, CG II had detached DD

Hans Lody

to convey the ambassador to New York, then reversed its course and steamed to within 150 miles west of Scapa Flow. CG I had slowed its journey home, and cruised some 200 miles northeast of the British naval base. Since nearing British territorial waters, it had been shadowed by HMS

Sheffield;

but, low on fuel, that ship had broken contact (with an exchange of friendly signals) earlier in the day. CG IV, after a rapid passage through the Skagerrak, held position 150 miles southeast of Scapa Flow. At 0100 on September 1, commanders of the three naval forces announced the existence of a state of war between the Third Reich and its archnemesis, Great Britain. Personal messages from Hitler and Admiral Raeder called for vengeance upon the fleet that had starved German children in 1919, and exhorted men and officers to make the opening blow of the new conflict a victory

“für Führer, für Reich, für Volk!”

At 0603 the first wave of planes—four Me Bf 109T fighters, eight Fi 167 torpedo bombers, and eight Ju 87C dive bombers from CG II—screamed over the unprepared British Home Fleet at Scapa Flow.

21

Within minutes, fourteen fighters, twenty-one torpedo bombers, and twenty-four dive bombers from CG I and CG III joined the assault. By 0630 the last of the raiders had departed, unable fully to evaluate damage to the Royal Navy because of the heavy pall of smoke blanketing the harbor. And that damage was severe. Two fleet carriers,

Glorious

and

Ark Royal

, burned fiercely before sinking. Two Great War vintage battleships,

Queen Elizabeth

and

Warspite

, had slipped beneath the cold waters minutes after taking two torpedo hits each. BC

Renown

, its magazine penetrated by a bomb, exploded, then sank in seconds—over a thousand men died with it alone. BB

Royal Sovereign

, serving as flag for the Home Fleet, lost its A-turret to a bomb and its propellers to a torpedo. The final tally was three capital ships, two carriers, a heavy cruiser, and three destroyers sunk, for the cost of four German planes. Additionally, of the remaining seven veterans of the British battle line at anchor that morning, all except the battle cruiser

Hood

carried some mark of German bombs and torpedoes, while Bf 109s had savaged every plane at Scapa Flow’s airfields. Even then, the trial by fire of September 1, 1939, for the Home Fleet was far from complete.

Expecting additional attacks from the German carriers, survivors of the Home Fleet sortied for southern bases and their own air cover. But the German carriers had no intention of risking a second attack. After recovering planes, CG I steamed for Kiel and the first of many “heroes’ welcomes” for the Kriegsmarine. CG II made maximum speed for the South Atlantic, and CG IV moved at flank speed toward Halifax, Nova Scotia. Torment by air for the Home Fleet had ended for the day, but their disorganized flight stumbled into the waiting U-boats of Submarine Groups I and V. Vice Admiral Kurt Slevogt, commanding SG I, was a model of Teutonic efficiency that day. He applied the convoy attack paradigm to the Home Fleet, using one submarine as a decoy while others lined up shots on its would-be attackers. By 2300, Slevogt’s tally included eight destroyers and three cruisers without the loss of a single U-boat. SG V’s commander failed to control the engagement. Committing his own boat to the attack early in the day, he paid the ultimate price. Two more of his boats fell to British depth charges, though it is probable that one of them managed to attack the

Royal Sovereign

, damaged and under tow, which capsized at 1651 that afternoon when a single torpedo struck it amidships.

Throughout the remainder of September, as German armored and infantry forces ground Poland beneath metal tracks and hobnailed boots, the Kriegsmarine ran amok in the Atlantic. U-boats savaged the Western Approaches, sinking thirty convoy escorts (including eighteeen fleet destroyers), three cruisers, and thousands of tons of merchantmen for a loss of only four submarines. CG II added three cruisers (

Exeter, Ajax

, and

Achilles

), four destroyers, and numerous merchantmen while operating near the mouth of Uruguay’s River Plate. It then refueled at neutral Montevideo before sailing for the North Sea and home. CG IV closed Halifax in mid-September, launching an air raid on its weakly defended harbor and shipyards before being warned clear of North American waters by the United States.

22

CG III, however, established a new milestone in naval history on September 12: the first carrier versus carrier battle.

Since September 1, CG III had been operating near the Straits of Gibraltar, interdicting British and French shipping (France had declared war on Germany on September 3). By remaining in the same area, Vice Admiral Gunther Lütjens confronted several risks, notably the concentration of enemy submarines and possible night attacks against his group by light forces from Gibraltar or French North African ports. However, he hoped to lure two British carriers,

Furious

and

Hermes

, from the British base at Gibraltar to the open sea, where they could be engaged.

By dawn on September 12 his task force had evaded or destroyed five submarine contacts, and he ordered an unhappy withdrawal to the northwest. But at 1023 scout planes reported that British Force H (three battleships, the two carriers, two cruisers, and a dozen destroyers) was not only at sea, but on the same course as CG III, at a distance of only 100 miles! Lütjens quickly ordered a strike force launched, retaining only four Bf 109s for Combat Air Patrol (CAP). His attack wave had no sooner cleared the deck than his radar detected a covey of British planes inbound. The next half hour revealed the true weakness of British carriers—their planes. The Fairey Swordfish, a biplane torpedo bomber with a top speed of less than 150 mph, stood no chance against the modern Bf 109s. Of the twenty-three attackers, fifteen fell victim to the fighters before they began their attack run. The remainder persevered, two actually surviving to launch their torpedoes (both missed) before falling into the sea. Only fourteen of the sixty-nine British airmen survived to become German prisoners. Lütjens dined with them that night, one of the fliers recalling that the admiral had toasted them: “To the bravest men I have ever met, and damn the criminals who make you fly that deathtrap.”

23

Map 1. “A Date Which Will Live in Infamy”

While the Germans rescued the downed fliers, their attack wave made contact with Force H. Brushing aside the pitiful British CAP, German torpedoes and bombs sank

Hermes

and severely damaged

Furious

, but not without a price. Of the fifteen bombers involved in the attack, seven failed to return to CG III, and three of those that did were so riddled with antiaircraft fire as to be usable only for spare parts. Clearly, attacking a prepared British fleet with such a small number of planes would cost the German light carriers dearly. Lütjens carefully considered that fact as Force H limped for home and CG III sped away to replenish its planes from its supply vessels in safety.

The Polish campaign ended on September 27, a visible testament to the power of the German Wehrmacht and Luftwaffe. When coupled with the successes of the Kriegsmarine, German victories offered Hitler the opportunity for considerable diplomatic suasion. In mid-October he hosted a meeting of several nonaligned European nations in Warsaw (amid the physical evidence of his nation’s military prowess), including Belgium, Luxembourg, Holland, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Hungary, and Romania. Hitler proposed the creation of a multilateral treaty between these nations and Germany. Each nation would enjoy favored trade status with the Reich and would benefit from its protection against external threats. In return, Hitler requested rights of military passage through signatory nations and long-term leases of land for naval and air bases. Finally, he warned that in these dangerous times no nation could afford to straddle the political fence, and that Germany would deal with its enemies as easily as with its friends.

On October 19, 1939, Germany, Finland, Hungary, and Romania signed Hitler’s Danzig Pact. After a twenty-four-hour conquest of Denmark on November 11 (according to a statement by Raeder, “to defend the Baltic Sea lanes from probable Anglo-French blockade”), Norway and Sweden reconsidered their stance and belatedly signed the treaty. Of course, the interdiction of the North Sea trade lanes by CG I and various U-boat groups during October and November probably helped Norway reach its decision.

On land, the winter of 1939-40 developed into the Sitzkrieg, or phony war, as the French slowly mobilized behind their “impregnable” Maginot Line. Meanwhile, British shipping, guarded by the Royal Navy and Royal Air Force, convoyed the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) to France and Belgium. Twice the German Navy tried to interfere with the convoys, only to discover the vulnerability of both carrier groups and U-boats to concentrated enemy air power. CG I lost two destroyers and 28 planes, as well as suffering light damage to the

Graf Zeppelin

on December 6, while SG I lost four boats, including the expert Admiral Slevogt, in the shallow Channel waters in early November. This established the pattern for the surface war at sea over the dark months of winter. Where British land-based air operated, the German carrier groups did not. Outside that range, those groups operated with a fairly free hand. In particular, the German Navy dominated the North Sea (especially after establishing its own land-based air in Denmark and Norway) and the Atlantic-Mediterranean shipping lanes.

Desperate to open the shipping lanes to the Mediterranean, allied surface forces sortied against the Kriegsmarine four times, losing two battleships, the only French carrier, four cruisers, and sixteen destroyers in exchange for a German cruiser and two destroyers (all three lost to French carrier planes). British and French submarines fared just as badly, with twenty lost in the area over the winter months. Unknown to the allies, the excellent German radar almost always identified the submarines before they submerged to attack, and operators immediately vectored destroyers against the would-be assailants.

The North Sea presented a different set of problems for both sides. In mid-October, Hitler had declared the North Sea—Baltic sea lane an open trade route, as long as merchant ships kept their bows pointed away from England. In addition, he removed all port duties and tariffs on goods entering Germany. American industrialists could not resist the strong profits in a lane not threatened by the U-boats operating near the British Isles. German trade with the United States boomed, while trade with Britain declined. Unless the Royal Navy could regain control of the North Sea, it could not stop the trade. Worse, the accidental torpedoing of an American luxury liner by HMS

Sealion

on December 18 threatened to turn U.S. public opinion against Great Britain. Events in Europe stymied President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who strongly supported Great Britain but faced an election in 1940 and a growing wave of support for Germany among voters.

In early January the Royal Navy attempted to take advantage of the short northern nights and the absence of

Graf Zeppelin

from CG I (in Germany for repairs following the engagement of December 6) by sending a Task Force composed of BC

Hood

, two heavy cruisers, and twelve destroyers into Norwegian waters. In near absolute darkness, an alert

Scharnhorst

used its radar to place accurate fire on the British force, then directed its ten destroyers in launching their Long Lance torpedoes into the inky night. Only one cruiser and five destroyers escaped this novel use of the new radar technology. For the gallant

Hood

, unscathed at Scapa Flow in September, luck had expired. A magazine explosion doomed the ship and its entire crew, as well as any chance for Britain to close Germany’s Baltic trade lanes.

By May 1940 the British situation had deteriorated at all levels. The Royal Navy had lost seven capital ships, four carriers, twenty-eight cruisers, and ninety-six destroyers, most of these to U-boats while escorting convoys. With supply lines to the East Indies interrupted, shortages in several strategic materials and petroleum products threatened to slow or stop British industry. British land forces in the Mediterranean operated on shoestring logistics, and British naval forces in Gibraltar and Malta hoarded precious munitions and consumables. From India to Singapore, Canada to Australia, raw materials were stockpiled and economic collapse threatened in numerous market sectors. And the United States, trapped between isolationism and German gold, remained unwilling to come to the aid of its old ally.