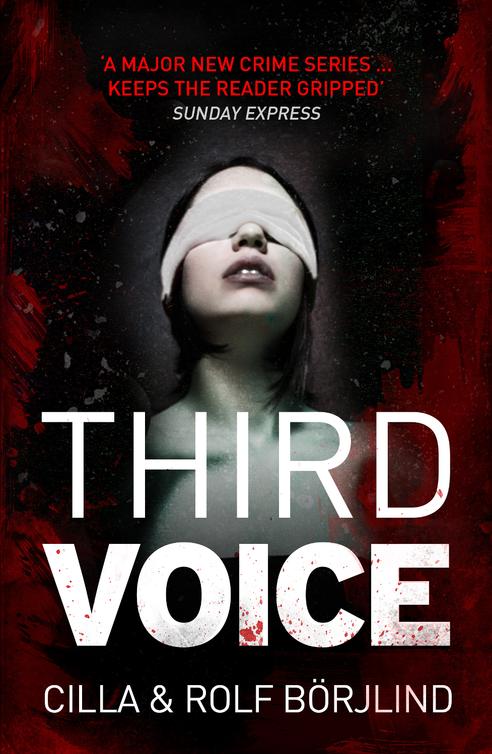

Third Voice

Authors: Cilla Börjlind,Hilary; Rolf; Parnfors

Cilla and Rolf Börjlind

Translated by Hilary Parnfors

- Title Page

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Chapter 13

- Chapter 14

- Chapter 15

- Chapter 16

- Chapter 17

- Chapter 18

- Chapter 19

- Chapter 20

- Chapter 21

- Chapter 22

- Chapter 23

- Chapter 24

- Chapter 25

- Chapter 26

- Chapter 27

- Chapter 28

- Chapter 29

- Acknowledgements

- Biographical note

- About the Publisher

- Copyright

Barefoot, I stand looking down from the roof. Nine floors below, I see the grey road. It’s empty and the city sleeps without a breath of wind in the air. I take a few steps along the edge and stretch out my arms for balance. A bird swoops down and perches a little way away. I think it might be a jackdaw. The bird looks out over the silent houses. We both have wings. Mine are white, its are black.

It’ll get light soon.

I take a few steps towards the jackdaw, carefully, so as not to scare it. I want it to understand why I’m here, at this time.

I want to explain.

I left my body last night, I whisper to the jackdaw, even before I was dead. I was already hovering over my body when he started beating me. I watched it all from above. I saw the straps cutting into my throat. He’d pulled them too tight. I knew that I’d suffocate. That’s why I screamed so horribly. It hurt so much. I’d never screamed like that before. That’s probably why he started hitting me, over and over again, and the heavy ashtray shattered my temple.

Now I feel the breeze.

It’s the first balmy breeze to come in from the sea in ages. The jackdaw looks at me with one eye, and far away I see the mighty golden Madonna. She stands on the highest hill, her face turned towards me. Did she see what happened last night as well? Was she in the room too? Couldn’t she have helped me?

I look at the jackdaw again.

Before I died I was blind, I whisper. That’s why it was all so terrible. We weren’t alone in the room, he and I. I could hear other voices. I was frightened of what I couldn’t see, of those men’s voices I heard, foreign words. I didn’t want to be part of this any more. It all felt wrong. Then I died, and it was just him and me left in there. He had to clean up all the blood himself. It took such a long time.

The jackdaw is still in the same place, motionless. Is it an angel bird? Did it get caught in a net and break its neck? Or was it hit by a lorry? Now I hear noises from the road down below, someone has woken, and I can sense the smell of burning rubbish all the way up here. Soon there’ll be people milling between the houses.

I have to hurry.

He carried me out in the dark, I whisper to the jackdaw. No one saw us. I was floating above it all. He lifted me into the boot of a car and folded up my thin legs. He was in a rush. We went to the cliffs. He laid my naked body on the ground next to the car, in the gravel. I wanted to reach down and brush my hand over my cheek. I looked so violated. He dragged me by my arms, far off in amongst the trees and rocks. And there he dismembered me. First he cut off my head. I wonder how he felt when he did it. He did it so fast, with a large knife. He buried me in six different places, far apart. He didn’t want anyone to find me. When he left I flew here. To this rooftop.

Now I’m ready.

Far away, in the mountains of the north, the first rays of sunshine are bursting over the ridge, the dew sparkling on the rooftops. A lone fishing boat is heading back into port.

It’s going to be a beautiful day.

The jackdaw next to me is falling out into the breeze with its wings outstretched. I lean out and follow it.

Someone will find me.

I know it.

‘Cut out of my murdered mother’s womb.’

Olivia tormented herself day and night. Dark, vile thoughts occupied her mind at night. During the day she hid herself away.

It went on for a long time, until she was more or less apathetic.

Until it couldn’t continue any more.

Then one morning, her survival instinct kicked in and pummelled her out into the world again.

There, she made a decision.

She’d complete her final term at the Police Academy and be a police officer.

Then she’d go abroad. She wasn’t going to look for a job. She was going to disappear, go far away, and try to reconnect with the person she was before she became the daughter of two murdered parents.

If that was even possible.

She followed her plan, borrowed money from a relative and set off in July.

Alone.

First to Mexico, the homeland of her murdered mother, to unknown places with unknown people and foreign tongues. She travelled light with only a brown backpack and a map. She had no plan and no particular direction. All places were new and she was nobody. She had to spend time with her inner self, moving at her own pace. Nobody saw her cry. Nobody knew why she sometimes just sank down by a stream, letting her long black hair flow through the water for a while.

She was in her own universe.

Before the trip, she’d had some vague thoughts about tracing her mother’s roots, and maybe finding some relatives, but she’d realised that she knew far too little about them for it to lead anywhere.

So she just got on a bus in a small town and got off in an even smaller one.

Three months later, she ended up in Cuatro Ciénegas.

She checked into Xipe Totec, the hotel of the flayed god, on the outskirts of town. At dusk, she walked barefoot to the beautiful square in the centre. It was her twenty-fifth birthday and she wanted to see people. There were coloured lanterns hanging in the plane trees with small groups of young people huddled beneath them, young girls in garish skirts and young boys with handkerchiefs stuffed into their trousers. They were laughing. The music from the bars drifted out into the square, the donkeys stood still by the fountain and many strange smells swirled through the air.

She sat on a bench like an outsider and felt very safe.

An hour later she headed back to her hotel.

The evening air was still warm when she sat down on a wooden veranda, looking out over the vast Chihuahua Desert, as the cicadas’ sharp song mixed with the clatter of horses’ hooves. She’d just treated herself to a cold beer and was considering having another. Then it happened. For the first time she felt some solid ground beneath her.

I’m going to change my surname, she thought.

I’m actually half Mexican. I’m going to take my mother’s name. Her name was Adelita Rivera. I’m going to change my surname from Rönning to Rivera.

Olivia Rivera.

She looked out over the desert in front of her. Of course, she thought, that’s how I’ll start over. Simple. She turned around and gestured with the empty beer bottle towards the bar inside.

She was going to drink the next beer as Olivia Rivera.

She looked out over the desert again, and saw the light breeze blowing a couple of dry bushes over the hot quivering ground. She saw a green and black lizard scamper up a three-branched prickly saguaro, she saw a couple of silent birds of prey glide off into the burning horizon and suddenly she smiled at nothing at

all, unhindered. For the first time since late summer last year she felt almost happy.

Simple as that.

That night she went to bed with Ramón, the young bartender who’d lisped a little as he politely asked her whether she wanted to make love.

She was done with Mexico. The trip had taken her to the place she’d needed to reach. Her next destination was Costa Rica and the village of Mal Pais, the place where her biological father had had a house. He’d called himself Dan Nilsson there, even though his real name was Nils Wendt.

He had lived a double life.

On the way, she made a number of decisions, all spawned by Olivia Rivera, from the strange power she had gained with her new surname.

One was that she was going to put her police career on hold and study history of art. Adelita had been an artist, weaving beautiful fabrics. Maybe they could connect in some abstract kind of way, she thought.

One rather more crucial decision concerned her outlook on life. As soon as she got back to Sweden, she would follow her own path. She’d been hurt by people she had trusted. She’d been naive and open, and had had her heart smashed to pieces. She was determined not to take that risk again. From now on she would trust one person alone.

Olivia Rivera.

It was late afternoon by the time she got out of the sea at a beach on the Nicoya Peninsula. Her long black hair fell down over her tanned body – she’d spent four months in the tropical sun. She climbed up on the deserted beach and threw a towel over her shoulders. A green coconut rolled back and forth at the water’s edge. She turned towards the sea and knew that she had to go over it again.

Right here, right now.

‘Cut out of my murdered mother’s womb.’

The image departed from her consciousness again. The beach, the woman, the moon. The murder. Her mother had been drowned in a spring tide, buried on the island of Nordkoster. Before I was born, she thought, she died before I was

born

.

She never got to see me.

Now she was standing on a very different beach trying to accept – much harder than trying to understand – the thought that their eyes had never met.

Being born unseen.

She looked out to sea. The ocean stretched all the way to the blazing amber horizon. It was about to get dark. Calm swells were moving in towards the land, soft warm waves rolling up towards her feet. In the distance she saw a group of dark heads bobbing around on the surface.

She pulled on her thin white dress and started walking.

Small grey-white crabs scuttled into their holes in the sand as she passed by, the water filling her footsteps behind her. She had walked along the beach for almost an hour, slowly, from Santa Teresa all the way out here, to the cliffs at Mal Pais. She knew it would be like this, that the images and thoughts would come flooding back.

That was the point of the walk.

She wanted to submerge herself in the pain again, one last time, she wanted to be prepared. In a few minutes she would meet a man who would take her back even closer to her mysterious past.

The man was sitting on a long tree trunk by the shore. He was seventy-four years old and had lived in the area his whole life. He had once owned a bar in Santa Teresa. Now he mostly sat on the veranda of his peculiar house drinking rum. He’d come to terms with most things. When his beloved boyfriend died a few years ago, the last thing keeping his flame of life alight

had disappeared with him. Breathe in, breathe out. Sooner or later it all comes to an end. But he didn’t complain. He had his booze. And his past. Many people had come and gone during his lifetime, some had stuck in his memory. Two of them were Adelita Rivera and Dan Nilsson.

And now he was about to meet their daughter.

The daughter neither of them had had the chance to meet themselves.

He regretted not bringing a swig of rum to the beach.

Olivia saw him from afar. She sort of knew what he was going to look like. Abbas el Fassi had told her. But she couldn’t be completely sure. So she stopped some distance away from the tree trunk and waited for the man to look up.

He didn’t.

‘Rodriguez Bosques?’

‘Bosques Rodriguez. Bosques is my first name. And you’re Olivia?’

‘Yes.’

Then Bosques looked up. When his old narrow eyes caught sight of Olivia’s face he shuddered. Not very noticeably, but enough for Olivia to get a clear flashback. That’s exactly how Nils Wendt had reacted when he’d seen her in a doorway on the island of Nordkoster last year, not having a clue who she was. Especially not that she was his and Adelita Rivera’s daughter. And Olivia had had no idea who the man in the doorway was either. That’s how they’d parted ways, and it was the first and last time she’d seen her father alive.

‘You’re a spitting image of Adelita,’ Bosques said in his croaky voice.

‘I’m her daughter.’

‘Sit down.’

Olivia sat down on the tree trunk, well away from Bosques, which he noted.

‘You’re very beautiful,’ he said. ‘Like her.’

‘You knew my mother.’

‘And your father. The big Swede.’

‘Was that what he was called?’

‘By me, yes. And now they’re both dead.’

‘Yes. You wrote that you had a photo of my mother?’

‘A photo and a few other things.’

Olivia had been given Bosques’ email address by Abbas el Fassi. Somewhere in Mexico she’d gone into an Internet café, emailed Bosques, explaining who she was, and saying that she was planning to come to Costa Rica and wanted to meet him. Bosques had responded very quickly. He only received personal emails once in a blue moon, and he told her that he had quite a few of her parents’ personal belongings.

He lifted up a small oblong metal box, red and yellow in colour, which had originally housed some very exclusive Cuban cigars, opened it and picked up a photograph. His hands were trembling slightly.

‘That’s your mother. Adelita Rivera.’

Olivia leant over towards Bosques and took the photograph. She smelled a slight waft of cigar. It was a colour photograph. She had seen a picture of her mother once before, on a photograph that Abbas had taken home with him from Santa Teresa last year, but this one was much sharper and more beautiful. She looked at her mother and saw that she had a slight squint in one eye.

Just like Olivia.

‘Adelita got her name from a Mexican heroine,’ said Bosques. ‘Her name was Adelita Velarde and she was a soldier during the Mexican Revolution. Her name became a symbol for women with strength and courage. There’s a song about her too.

La Adelita.

’

Bosques suddenly started singing, softly, in gentle melodic Spanish, the song about the strong and brave woman with whom all the rebels had fallen in love. Olivia looked at him, at the photograph of her mother, the old man’s trembling song

touching her innermost soul. She glanced up and looked out over the ocean. The whole situation was absurd, magical, far removed from her daily life in Stockholm.

Bosques fell silent and his gaze sank down into the sand. Olivia looked at him and realised that Bosques was also grieving. He had been a close friend of her mother and father. She moved nearer, almost right next to him. Carefully he put her hand in his. She let him do so. Bosques cleared his throat a little.

‘Your mother was a very talented artist.’

‘Abbas told me. He sends his regards.’

‘He’s very good with knives.’

‘Yes.’

‘Shall we go up to your father’s house?’

‘Soon.’

Olivia turned towards the water again and saw a massive wave pulsating through the sea. All the dark heads she’d seen earlier were hoisting themselves up onto surfboards. They caught the wave with their bodies hunched over and were carried away from the burning horizon at furious speed.

She got up.