This Great Struggle (6 page)

Read This Great Struggle Online

Authors: Steven Woodworth

All the while Brown was planning what he confidently believed would be his greatest stroke against the slave power. He would lead a band of abolitionist fighters into slave territory somewhere in the southern Appalachians. There escaping slaves would flock to join him, and he would organize them into a freed-slave republic that would, he hoped, grow until it overthrew the slave-tolerant U.S. government and replaced the imperfect U.S. Constitution with its own charter, over which Brown had labored many an hour by candlelight in Kansas and New York. When Brown presented the plan to his friend, black abolitionist Frederick Douglass, the latter was appalled. The plan seemed like suicide and would discredit the abolitionist movement. Nevertheless Brown and his small band of adherents, both white and black, forged ahead.

In October 1859 he led them to the U.S. arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia), seizing the undefended facility and taking hostages. Brown hesitated before leading his raiders away from Harpers Ferry, however, and soon found himself surrounded by Virginia militia. No slaves came to join him. That particular section of Virginia contained relatively few slaves. Instead of help from those he had hoped to free, Brown soon found that federal authority had arrived in the person of U.S. Army Lieutenant Colonel Robert E. Lee, supported by a company of U.S. Marines, hastily shipped up from the Washington navy yard. When Brown refused Lee’s summons to surrender, Lee sent in the marines, who successfully stormed Brown’s remaining enclave within the arsenal.

Though badly wounded, Brown survived, and Virginia authorities lost no time in arraigning and trying him for treason against the state of Virginia and other crimes. The trial’s outcome was never in doubt. Guaranteed a place on the gallows before year’s end, Brown conducted himself with impressive dignity, winning the grudging respect of his captors and the admiration of many across the North who had initially recoiled from the violent and lawless nature of his raid. Southerners took note of and exaggerated the degree of northern sympathy for Brown. The most radical of slavery advocates, known as Fire-Eaters, warned that he was a harbinger of the bloody intentions of the abolitionists toward all white southerners.

One Fire-Eater, Virginia agricultural writer Edmund Ruffin, acquired some of the pikes, or spears, Brown had brought with him in hopes of arming the slave allies who never came. Ruffin sent one pike to each southern state capitol as a graphic reminder to his fellow white southerners of what the North supposedly wanted to do to them and their families. When Virginia authorities hanged Brown that December, surrounded by almost the whole of the state’s militia, the septuagenarian Ruffin, complete with flowing white hair, had himself temporarily inducted into the corps of cadets of the Virginia Military Institute so that he could be on hand to have the pleasure of seeing the famous abolitionist fighter twist in the wind. Commanding the contingent of cadets was one of their professors, stern Presbyterian and Mexican War veteran Thomas J. Jackson. Jackson admired the courage and calmness with which Brown faced death but disapproved of his cause.

Brown’s raid and the subsequent publicity surrounding his trial and execution, including displays of public mourning in some northern cities, culminated in an entire decade of political and sometimes violent and bloody sectional strife over the issue of slavery. Each clash, whether in the national capital or in places like Lawrence, Kansas, or Harpers Ferry, Virginia, had intensified the bitter feelings between North and South. Thus polarized, the nation faced the election of 1860.

The Democratic convention took place in Charleston, South Carolina, the most extreme proslavery city in the most extreme proslavery region of the most extreme proslavery state in the Union. Local crowds packing the visitors’ gallery roared their approval for every proslavery speech and jeered any mention of the candidacy of Stephen Douglas, whom they hated for having denied the inherent right of slavery to go into all of the territories regardless even of the majority vote of white inhabitants.

Through more than one hundred ballots, the convention could not achieve the two-thirds vote needed to make a nomination. Southerners had more than one-third of the delegates committed to stopping Douglas or any candidate not completely dedicated to slavery expansion. Douglas had a solid majority of delegates behind him, and this time his supporters, many of them from the Midwest, were tired of backing down to the demands of the slave power every four years—and then paying the price for it at the polls in the North. Unable to nominate a candidate, the convention turned instead to selecting a platform, but when the majority refused a southern demand that the federal government actively protect slavery in every territory, southern delegates walked out. An attempt to restore party unity at a special convention in Baltimore several weeks later also broke up over the issue of slavery, and the severed wings of the Democratic Party nominated rival presidential tickets—Vice President John C. Breckinridge for the southern Democrats, Douglas for what was left of the national Democratic Party.

During the period between the first Democratic convention in Charleston and that party’s attempt to reconstitute itself in Baltimore, the Republican Party met in Chicago, Illinois, and, passing over front-runner William H. Seward as being perhaps too controversial a figure, instead nominated Lincoln. The Illinois lawyer had seemed like the ideal candidate, dedicated to the party’s cause of halting the spread of slavery yet without the harsh edge that public perception attributed to Seward. In a speech in New York City the preceding February, Lincoln had showed an ability to articulate Republican principles in surprisingly clear and eloquent language, arguing persuasively that what the Republicans wanted was a return to the thought and policies of the founders of the republic, who had wished to contain slavery so that it would be “in the course of ultimate extinction.” Lincoln also had common-man appeal and a set of very savvy political managers.

The 1860 campaign was not to be a three-way race. As if the field of candidates were not already crowded enough, a group of former southern Whigs, dissatisfied with both the Democrats and the Republicans, held a convention and formed itself into the Constitutional Union Party. The new party nominated John Bell of Tennessee as its presidential candidate—the fourth major-party candidate in that year’s race—and, in the best of old-time Whig tradition, declined to adopt any platform other than “the Constitution and the enforcement of the laws”—a creed to which every party claimed to subscribe. Voters understood that what the Constitutional Unionists stood for was a moderate proslavery position without the Fire-Eaters’ constant demands for slavery expansion and strident threats of secession if their demands were not met or their candidate was not elected.

The election turned into two separate two-way races: Bell versus Breckinridge in the South and Lincoln versus Douglas in the North. Breckinridge carried the Deep South and Bell the Upper South. Douglas garnered more votes than either but carried only Missouri and half of New Jersey. Lincoln was the top vote getter, edging out Douglas in all the rest of the free states and locking up an electoral majority with scarcely more than 39 percent of the popular vote. Curiously, this was not because his opposition was split three ways. Even if all the votes cast for all three of Lincoln’s opponents had been cast for one man, Lincoln would still have won since he carried nearly all of the northern states by moderate to narrow margins but garnered virtually no votes at all in the South.

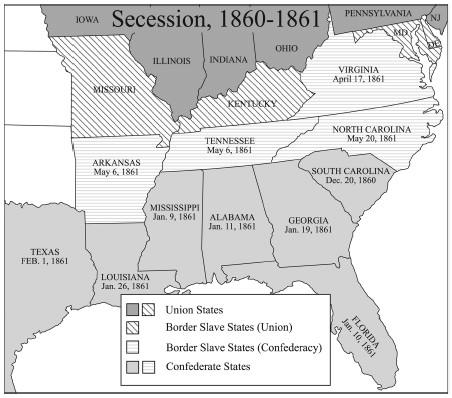

THE SECESSION OF THE DEEP SOUTH STATES

Throughout the campaign, southerners, particularly the Fire-Eaters, had loudly and frequently repeated that they would take their states out of the Union if any “Black Republican” was elected. At news of Lincoln’s triumph, secessionists in all of the slave states went to work to make good on their threat. By a campaign of manipulation and voter intimidation, they strove to bring about secession. South Carolina led the way on December 20, 1860, and thereby undercut the attempts of southern unionists to stop the momentum for secession by persuading southern voters to wait until all of the slave states could go out together. Though a two-week delay followed, South Carolina’s action was like the bursting of a levee, as one after another of the slave states seceded. During January 1861, five more Deep South states declared themselves out of the Union, and Texas, on February 1, became the seventh state to do so.

Later that month representatives of the seceded states met in Montgomery, Alabama, and constituted themselves the Confederate States of America, electing as their president Mississippi Senator Jefferson Davis. Davis, a West Point graduate and Mexican War veteran, originally coveted a military appointment in the newly forming Confederate army, but he accepted the presidency and prepared to lead the new slaveholders’ republic. The Confederacy, seeking further legitimacy, adopted a constitution modeled on the U.S. Constitution but altered to recognize slavery specifically. They knew what their revolution was intended to protect, even if some of them would later deny it and claim they were fighting for state rights. Another difference from the U.S. Constitution was that the Confederate constitution limited its president to one six-year term without eligibility for reelection. Davis was to serve as provisional president until a regular president could be elected in the fall of 1861 and inaugurated the following February. As it turned out, no candidate opposed him, and the Mississippian was elected to succeed himself and become the Confederacy’s first—and only—regular president.

While the Deep South states seceded and formed a rival government, lame-duck President Buchanan did nothing. In the face of his idleness, rebellious state militia throughout the Deep South seized every federal installation in those states except for two: irrelevant Fort Pickens outside the harbor of Pensacola, Florida, and all-too-relevant Fort Sumter inside the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina. Much to Buchanan’s dismay, the commander of the seventy-six-man U.S. Army garrison at Charleston had moved his troops on Christmas night 1860 from the indefensible old Fort Moultrie to the new and modern (as well as incomplete) Fort Sumter, where it would be much more difficult for rebellious militia to bring him to grips. Southern leaders cried foul and demanded that Sumter be evacuated as part of an overall U.S. government acceptance of the secession of the southern states. Such acceptance did not seem unlikely in view of the fact that Buchanan, in his last State of the Union Address, had proclaimed that states had no right to secede and that the federal government had no right to stop them if they did.

Public opinion in the North was divided. Some northern Democrats, naturally hostile to Lincoln and his platform of limiting slavery expansion, were inclined to sympathize with the seceding states. Horace Greeley, influential editor of the

New York Tribune

and one of the most prominent Republican journalists in the country, urged, “Let erring sisters go in peace,” and some other Republicans took up his refrain. This was not so much because they desired to see the Union broken up as because they were afraid that the Buchanan administration would knuckle under to the southern threat of secession and agree to some sort of compromise that might negate all that antislavery Americans had achieved in the recent campaign.

The Cotton South seemed unified and determined, the North confused and uncertain. The Upper South—Virginia, Maryland, North Carolina, Kentucky, Arkansas, and Missouri—seemed to teeter on the brink of secession, as the Fire-Eaters in those states had fallen just short of their goal of rushing secession past a skeptical electorate. Secessionists in the Upper South tended to believe that what their cause needed was some aggressive action on the part of the Confederacy to demonstrate that it truly was independent and was not going to put up with any trifling from the Lincoln administration. As Virginia Fire-Eater Roger Pryor told a crowd in Charleston, South Carolina, the way to bring Virginia out of the Union and into the Confederacy was to “strike a blow.”