This Side of Jordan (13 page)

Read This Side of Jordan Online

Authors: Monte Schulz

“Daddy,” said Rose, walking now toward him, hair blowing across her face. “Please put the gun down.”

“They're thieves, Rosa Jean. Don't trust them.”

Chester had circled clear around Harper, standing just behind his right shoulder. Harper's rifle still pointed toward Alvin's back. Rose stopped fifteen feet from the water trough, her arms held out imploringly to her father. “Daddy, please!”

Out of the corner of his eye, Alvin caught a glimpse of Rascal standing motionless by the rear corner of the house, watching from the shadow of the eaves. Then he heard Harper release the hammer, and a moment later the barrel of the Sharp's rifle struck the dirt behind his feet.

“Goddamned sonsofbitches!” said the old man, and sunk backward to sit down on the trough. Rose walked forward another three steps, muttering something under her breath indistinguishable in the wind, and got close enough to her father to have her dress sprayed with blood an instant after Chester placed his pistol against the back of Harper's head and pulled the trigger.

The blast echo circled the yard and chased out across the fields. Charlie Harper's body lurched into the trough with a large splash. Stink of gunsmoke filled the dark.

Paralyzed with shock, Alvin found himself utterly transfixed by the sight of Charlie Harper bobbing in the black water. As Rose drew near, she whispered, “Daddy?” and leaned over the trough.

“Well, I guess that plan was a dud,” said Chester, his gun still held out in the air where Harper's head had just been. “A fellow really ought to cut out boozing after work.”

Dust stung Alvin's face, forcing him to look away from Rose and the water trough. He sought out the dwarf by the north side of the farmhouse and found that Rascal was gone. Chester jammed the pistol back into his waistband. He grabbed the handle of the pump and jerked it twice to draw fresh water from the well. As Chester ladled it into his cupped palms, sucking a drink, Rose grabbed up her father's rifle from the dirt beside the trough. Cocking the hammer, she swung the barrel around to Chester's direction, but he had already drawn his revolver again.

Alvin watched dumbfounded as Chester calmly took aim and shot Rose through the chest.

She fell away from the trough, landing flat on her back, a small black stain from the wound soaking the hole in the front of her chemise. Her eyes were wide open, staring up into the night sky. Her left foot twitched for a couple more seconds, then stopped altogether.

Another gunshot echo faded across the dark.

Chester stared at her a little while, revolver drawn and pointed, then shook his head, put the gun away again, and washed his hands clean under the pump spout. He rubbed them hard, scraping and scrubbing with his thumbs and fingertips.

Alvin had lost all feeling in his limbs.

The rising water floated Harper's body to the rim so that his hands appeared determined to try and grip the edges. A vile taste crept up into the back of Alvin's throat and he coughed harshly. Vertigo came and went. That section of Charlie Harper's face disintegrated by the exit wound remained underwater.

Chester let go of the pump handle before the trough could over flow. He took a handkerchief out of his breast pocket and used it to dry off his hands. Then he told Alvin, “She'd have killed us both. We're lucky I saw her.”

Alvin stared at Rose, lying just below him. The dead held no particular fascination for him, having seen over the years his Uncle Otis, old Grandpa Chamberlain, his second-cousin Leroy, and a traveling salesman give up the ghost right before his eyes on the farm in Farrington. Funerals followed harvest celebrations as the most popularly attended ceremonies in the county. None of the casket dead resembled themselves. Faces all waxy and pale. Lips and brows painted. Eyes stitched shut. That was the difference. Here, Rose looked prettier in death's shadow than she had sitting on the bed indoors. It spooked Alvin. If he leaned over her, she'd be looking him right in the eye. The stain had quit, just a damp soiled patch on the fabric, requiring only a good scrubbing with soap and vinegar. Her eyes needed closing, though. Otherwise, she wouldn't get her reward. At every wake, Granny Chamberlain said,

God's sweet smile is too glorious to behold with white eyes revealed.

As Alvin bent down to close Rose's eyes, Chester leaned forward and grabbed him by the wrist. “Don't touch her. Don't touch either of them. Just leave them where they are.”

Then Chester walked off toward the back door, his blue suit jacket fluttering in the wind. Thoroughly terrified, Alvin looked once again for Rascal. The dwarf had been by the rear of the farmhouse, watching everything. Afterward, he had run off like a scared rabbit. Alvin went over to the rail fence for a look into the fields. It seemed even darker now than when Harper had led him out of the barn. Trees only a few dozen yards away were all but invisible, just big hazy shadows somewhere out beyond the fence. Alvin stopped breathing and listened to the wind hissing through the grass on the dark Kansas prairie.

The back door slammed shut and Chester came out into the yard, carrying the thirty-dollar Victrola under one arm and a flat piece of wood under the other, a narrow shelf from one of the white kitchen cabinets. He walked over to the trough and placed the wood upright against the pump. Then he took a pocketwatch out of his vest, checked the hour, and headed to the Packard, announcing that they had to go. Rascal walked out of the barn loaded up and ready to depart, his wool blanket in one hand, Alvin's bedroll in the other. He went only as far as the middle of the yard, where he stopped and waited for Alvin to pay his last respects at the trough. Back around the rear of the house, Chester started up the car.

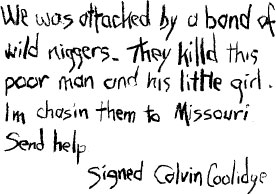

Both bodies looked like genuine Farrington farm corpses now, dead as yesterday. Wind had partially covered Rose's hair and fingers in dust, and clouded her eyes. If she hadn't yet beheld the Lord, she surely would in the next hour or so. Alvin came around the trough and found himself facing the board Chester had laid up against the pump. It was a message scribbled in charcoal, intended for whoever found Rose and Charlie Harper. It read:

T

HE DWARF WADED AT THE SHADY CREEK BOTTOM

in cold water up to his kneecaps, the suspender straps to his short denim overalls hanging loosely at his side, insects buzzing about his sunburned ears. Overhead, cottonwoods rustled and shook, fluttering leaves and dry bunchgrass down into the creek bed behind a narrow two-story framehouse on the great Nebraska prairie. Alvin Pendergast tossed his cap and farm shoes and socks underneath a fallen cottonwood log, then rolled up the cuffs of his work trousers and dangled his feet off the log into the narrow stream. Cold water numbed his toes and they tingled when he withdrew them from the current. Brushing a shock of hair off his forehead, he watched Rascal squat in the creek like a duck and fish the sand with his fingers, sloshing in quick circles, making paddling motions and humming to himself. Chester had taken the Packard and headed back up the highway to Stantonsburg: pop. 1328. He had told them to wait down in the creek bed until he came back. By Alvin's guess, that was two hours ago. Feeling a little better today than he had all week, Alvin wanted to go over town him self, buy a soda pop and have a look around, maybe find a pretty girl to jolly at the sweetshop, get her going with a nifty Ford joke or two

(“Why is a Ford like a bathtub? Because you hate to be seen in one!”).

He liked that idea. What was the use of traveling around, he thought, if you don't go nowhere?

“The flora and fauna of our Republic,” said the dwarf, “are quite fascinating when one takes care to observe them in their natural habitat. I once kept a grand collection of lady bugs in a Mason jar for a season of breeding.” He bent further and sunk his elbows into the water, dredging a trench in the creek bottom and rising up with two handfuls of mud. “Creatures of a lower order have always been a great interest of mine.”

“My cousin Frenchy eats crawdads cold,” said Alvin, dunking his toes again. “Don't ask me why.”

The water felt better now, less icy. The farm boy sunk his legs in up to his calves and sloshed around. It was hot out. The creek bed was cooler than up on the prairie, but Alvin still found it generally stifling. If the water had been deeper, he'd have already dived in and had himself a swim. He splashed lightly with his feet, watched the ripples expand. He liked fooling around in the middle of the day. Work was for saps. Water bugs skittered across the surface. A moldy odor of decaying vegetation on the muddy banks floated in the air. He asked the dwarf, “Can you swim?”

“Actually, I've never tried.”

“Scared of drowning, huh?” Alvin smirked, picturing the dwarf flailing his arms and sinking like a rock. Alvin himself had learned to swim when he was three, taught by old Uncle Henry who couldn't swim a lap in a bathtub anymore.

“Of course not. In fact, I'm sure I could manage quite well. My Uncle Augustus once swam across Lake Michigan in a rainstorm. He assured me buoyancy runs in the family.”

“I didn't ask if you float or not,” Alvin said. “I asked if you ever been swimming.”

The dwarf's hand shot down into the water. “Ahhh⦠there⦠devil, devil, devil!” It came up empty, three tiny streams of soggy sand leaking between his fingers. He looked over at Alvin. “Do you suppose there are any snapping turtles hereabouts?”

“I never met nobody before who couldn't swim,” Alvin remarked, letting his legs slide down a bit further off the mossy log. Sunlight sparkled on the current. Maybe he'd just go ahead and jump in. His cotton shirt and brown trousers were filthy, and needed washing. “Seems like something everybody ought to be able to do. Like walking, or riding a horse.”

“When I was a child,” replied Rascal, “we owned a stable of race horses down in Kentucky. People came from as far away as India to buy them from us for all the great competitions around the world. I believe we won the Queen's Steeplechase on more than one occasion.”

“I'd go swimming everyday in the summer if I didn't have chores to do,” said Alvin. He splashed water in the dwarf's direction, hoping to soak him. Half the time he and Frenchy went fishing, they wound up giving each other the works and riding home in Uncle Henry's Chevrolet dripping wet. “My cousin and me'd go swimming in the Mississippi Saturday mornings and be back home for supper. Swam all the way across once, like Johnny Weissmuller. Dove off the Illiniwek Bridge, too. Just to scare people who never seen someone do it before.” Rascal waded across the creek to study a pool worn by erosion into the far bank. “Do you see these bugs here?” He flicked his fingers lightly on the murky water lapping against the bank. “If I had a jar, I'd collect some and take them with us. Do you know, none of them have ever been more than a foot or so from this spot in their entire lives? It's a fact. They're born, grow up, mate and perish right here in the mud by this little creek. What do you suppose they know about life?”

“They're bugs. They don't have a need to know nothing.”

“So you say.”

“So I know.” Alvin dropped off the log into the cold creek water, making a big splash. He really wished Chester had taken him into town for a hotdog and a soda pop.

Plucking violets off the embankment farther downstream, the dwarf remarked, “Are you aware that amphibians are the precursors of modern man?” He dipped his hands into the stream, letting the current wash over the pretty wildflowers.

Alvin began kicking about, digging his feet in the sand. “Pardon?”

“Well, millions of years ago, we crawled out of the primordial swamp to establish civilization, while our cousins, the amphibians, remained behind.”

The dwarf released the wild violets into the stream and saw them float away into the splintered shadows. Alvin watched Rascal wade off down the creek, exploring the bank as he went, dipping his hands into the water when he saw something of interest, letting the sluggish current wash over his bare legs.

His own two legs growing numb from the cold, Alvin sloshed his way back to the damp sedge and climbed up onto the grass. Threads of sunlight like silver spider webs shone through white poplar leaves. He felt drowsy now, and hungry. All he'd eaten were buns for lunch. Chester had refused to let them visit a café. Clearing a place to sit amid leafless stems of scouringrush, the farm boy told the dwarf, “I guess I wouldn't mind lying in the mud all day. What makes us so smart? Maybe we ought to've stayed right where we were. Been better off. Most of us, anyhow.”

“Evolution is not a matter of choice.” Rascal refastened the shoulder buttons on his romper. “Rather, I believe, it's a form of destiny.”

“Favoring frogs and salamanders, huh?” Alvin laughed. Aunt Hattie had always maintained that evolution was a hokum which denied God's bitter miracle of life. She believed Noah strolled out of the ark on December 18th, 2348 B.C. and that's when the modern world began. Who's to say she wasn't right? Nobody had even half the answers. Life was too damned confusing.

“I collect them, of course,” said the dwarf, wading back toward the shore. “Studying one's past is invaluable for understanding one's place in the world. Do you think we'll eat soon?”

A dozen yards downstream, Rascal sat down in the soggy sedge and rinsed the mud from between his toes. Alvin climbed back up onto the rotting log. Balancing on one foot, the farm boy picked his nose. Meadowlarks chattered in the cottonwoods. Leaves fluttered down into the creek bed. Alvin walked to the end of the log and balanced above the stream. His sister Mary Ann could turn a cartwheel on a worm fence without falling off. Alvin searched for stream minnies in the creek bed. He watched the dwarf scramble up from the water and sit down in a pretty patch of blue verbena that grew near a thicket of sandbar willows where he put his shoes back on. Rascal said, “If I lived around here, I'd want to have lots of neighbors close by.”

“You mean, shouting distance?”

“If you will. Only through a life of society do men truly flourish.”

“Not me,” said Alvin, turning a circle on the log, careful not to slip off. His bare feet didn't offer much purchase on the damp moss. “I'd keep people about a mile off, so's I wouldn't have to hear 'em yammering all day long. Most folks talk too much.”

“I can recite by heart the inaugural addresses of nine Presidents of the United States. Uncle Augustus taught me when I was only six.”

“That'll earn you a living.”

The dwarf pulled his legs up under his chin and rocked backward. “I've often thought I ought to be a newspaper man, perhaps a city editor. I'm sure I have many of the correct qualifications. I can read quick as the wind and my grammar is excellent.”

“Why not just be President?”

“I've considered it.”

“You'd have to wear one of those tall black Lincoln stovepipes, you know? Think they got one big enough for that head of yours?” His laughter echoed loudly down the creek. He liked joking the dwarf. It passed the time.

Rascal frowned. “There's no cause to be cruel.”

Tired of the creek, the farm boy paced to the end of the cottonwood log and hopped off into the long grass. He picked up his cap and went to put on his shoes. “I'm going up to the house and have myself a glass of lemonade.”

“Wait for me!”

Â

Up on the Nebraska prairie, a light wind pushed across dry fields of Indian grass and flowering thimbleweed and bush clover, trading hay scents and dust. Overhead, the summer sky was blue and clear. The old gray framehouse was sheltered by a dense grove of common hackberry trees and a thick bur oak in the front yard. Red berries of a bittersweet vine draped the downstairs sleeping porch, and the backhouse under white poplars by the creek was shrouded at its rear in wild grape and poison ivy. A one-horse shovel plow and a Mayflower cultivator lay beside a dusty tractor near the barn, and a collection of milk pails and peach baskets were piled like junk next to a perforated bee-smoker beneath an old plum tree. Alvin thought maybe the fellow who owned the farm used to be more prosperous. Maybe life had given up on him.

The gravel driveway out to the county road was empty.

The farm boy listened to the bleating of sheep from somewhere across the fields. He walked under a sagging laundry line to the rear of the house where the kitchen door had been left ajar. His shoes kicked up dust wherever he strode. A familiar stink like rotten crabapples traveled here and there on the breeze. He brushed a curious bumblebee off his forehead and went over to study a tall wire birdcage framed in wood planks that stood almost as high as Alvin himself. There were still piles of dried shit on the dirt floor, but a foot-long section of chicken wire was ripped away near the bottom and he guessed some slick old fox had torn into it one night and had himself a snack.

Chester had told them the fellow who occupied this house was an old pal of his from Black Jack Pershing's army, but he also made them promise to stay hidden until he got back from town, so Alvin guessed it was another lie. Chester had driven the Packard up to the front door and invited himself inside for a drink of water. Hadn't bothered to knock or call out. Just went in like that. He came out five minutes later, rolling a Walking Liberty half-dollar over his knuckles and whistling a tune. He said he was going downtown to fix himself up with a shampoo and shave, then settle some business arrangements for the afternoon.

“It's the roving bee that gathers the honey,”

Chester had told Alvin as he got back into the Packard. Then he had driven off and left them.

To Alvin's eye, the house looked poor, or maybe the owner was just tired. Then again, maybe he was occupied most of the day smuggling corn whiskey and Chester had come to help him out of a fix. But if Chester had a plan doped out, he wasn't sharing it yet. Since Kansas, he'd just driven them around, visiting storehouses in small towns, cutting hootch in swill tubs, selling Scotch whiskey through the backrooms of pool parlors in old beer-jugs, and joyriding through the countryside in a hired liquor truck. For helping with the loading and unloading of whiskey barrels, and changing a flat tire now and then, he had paid Alvin fifteen dollars a week, and given the dwarf another thirty dollars for putting over a pretty fair applejack recipe and devising a scheme that involved the construction of pineapple bombs. There hadn't been any further talk of bank robbery since Kansas. Chester hadn't allowed it and both the farm boy and the dwarf knew how to hush up. None of them mentioned Charlie and Rose Harper at all. Lately, though, Alvin had been having bad dreams, and they weren't just fever.

The narrow sleeping porch was screened-in, but the back door leading to the kitchen was flimsy and rattled loose when the wind gusted. Alvin heard the dwarf thrashing up through the leafy milkweed above the creek, so he went inside.

The house was dark and cool. He listened to a mantel clock ticking in another room. Floorboards creaked underfoot. The pale lime-green kitchen smelled of coffee grounds and pipe tobacco. The latest issue of

Farm & Fireside

lay open on the table in the middle of the room. Filthy plates and cups were stacked in the sink. The ceiling was cracked and water-spotted. Window curtains were soiled. He looked in the icebox and saw only a bottle of milk and a chunk of cheese. Not much to eat. Except for a few canned goods and cornmeal, most of the pantry shelves were empty, too. Didn't this fellow ever go to the grocery store? Probably he was a bachelor, or a widower like Uncle Boyd, Alvin thought, as he opened a cupboard next to the cook stove in search of a clean glass. No woman would let her kitchen look this sore. He found a glass and brought it to the sink and ran cold water from the tap, then had a drink. He felt strange being indoors without having been invited. He had already been partner to a bank robbery and the killing of a fellow and his daughter, and he felt sick and lousy about it. He hadn't known any of that was going to happen. Over and over Rascal said it wasn't their fault, yet even though Charlie Harper had stuck a rifle in his face, Alvin still felt awful guilty. If the Bible was true like Aunt Hattie claimed, then he was probably going straight to hell when all he had wanted to do was stay out of the sanitarium. He might've jumped off a train and joined some workers at a tent colony or hired himself a cheap boardinghouse room and slung hash in a buffet flat. It needn't have amounted to much. Trouble was, he was getting sicker now and worried that sooner or later he'd have to see a doctor for the consumption, and he knew what that would mean. He supposed his daddy was burned up about him skipping out on his chores and all, while his momma sobbed after supper now and then. Alvin presumed his sisters were probably fighting over who'd be getting his room. He hadn't meant to run off for good. That was certainly a mistake, but what was done was done. Now he wished somebody would come along and tell him what he ought to do next.