Three Lives: A Biography of Stefan Zweig (46 page)

Read Three Lives: A Biography of Stefan Zweig Online

Authors: Oliver Matuschek

The letters he wrote on his travels remind us of times that he thought were long gone. It was just like his Russian tour: he barely had a minute to himself between engagements. This was a long way removed from the ideals that he had set forth in his 1926 essay

Reisen oder Gereist-Werden [Travelling or Being Travelled

]. Instead of being left alone to explore new places on his own, which was what he liked best, he could scarcely go anywhere without an entourage these days:

It’s just crazy here. Today, having been up all night working on a speech, I have to (1) call on the President of the Republic, (2) go to the Historical Museum, and (3) attend a reception at the Academy, where I have to give another speech. On Sunday the Foreign Minister gave a lunch party for me (60 persons, the most beautiful women), and afterwards we drove out to the most beautiful house in the most beautiful countryside I have ever seen. It’s all insanely wonderful, but I am being pulled in every direction and run ragged, I’m losing a kilo in weight every day with all the rushing around and having my photograph taken—but Brazil is incredible, I could cry my eyes out at the thought of having to leave. [ … ] I’m just dreading all the public attention, having new pictures of me in all the papers every day. [ … ]

I am so happy to have been here—and I can’t begin to describe the reception they have given me, for the past six days I’ve been the new Marlene Dietrich.

28

The next day found him in equally distinguished company: “I’m a kind of Charlie Chaplin here”,

29

he wrote this time—and not without reason: after the tour his publishers compiled an album of all the newspaper cuttings relating to his visit. The great writer is feted in dozens of glowing articles, and nearly every one includes the obligatory photo of him, smartly dressed and surrounded by women in all their finery, the men in dark suits, at formal banquets, behind a bank of microphones, and with a bouquet of flowers or even a coffee cup in his hands.

Travelling on to Argentina, where Zweig had been invited to attend the International PEN Congress (though he had declined the offer to chair the proceedings), his euphoria quickly evaporated. Because the event was attended by people from all over the world, every word spoken was translated consecutively into three languages, which meant that the already interminable debates became even more painfully protracted. Moreover the problems back home in Europe now caught up with him again, and when Emil Ludwig addressed the Congress as a representative of the German PEN Club in exile, Zweig was given a hard time by the press:

The newspapers pursue one from morning till night with photographs and stories—there was a big picture of me crying (!!!) during Ludwig’s speech. Or that’s what the screaming headline claimed—in actual fact I felt so disgusted when I heard us being portrayed as martyrs that I held my head in my hands to avoid being photographed, and that was the very image they chose to photograph—and then made up their own caption. I find this whole carnival of vanities quite repulsive.

30

When the Congress ended he embarked on the return sea voyage, which took several weeks. His new-found passion for Brazil knew no bounds, and he seemed disposed to applaud virtually every aspect of this paradise that he had discovered for himself in just a few days. It had not escaped his notice, for example, that large sections of the population here lived in the same kind of poverty that had so moved him when he travelled to India before the war. Yet in his notes he paints a rosy picture of life in the poorer parts of the city, portraying it as a colourful mix of different races where people seemed to be happy, despite their wretched conditions.

At any rate he had found material for new books. On the steamer that brought him back to Europe he was already studying the life of Magellan, the first man to sail around the world, whom he had chosen as the subject for another essay in the mould of

Sternstunden der Menschheit

—which he subsequently expanded into a whole book. And years later his book

Brasilien—Ein Land der Zukunft

[

Brazil—A Land of the Future

] appeared, incorporating many experiences and observations from this 1936 trip. But by the time this book came out, he would be back in South America again.

NOTES

1

Stefan Zweig to Romain Rolland, 25th February 1934. In: Briefe IV, p 469.

2

Zweig F 1947, p 368.

3

Stefan Zweig to Lavinia Mazzucchetti, 9th January 1934. In: Briefe IV, p 469.

4

The novel Rausch der Verwandlung, discovered in his literary estate, was eventually published in 1982 (Zweig GW Rausch der Verwandlung).

5

Zweig GW Welt von Gestern, p 434 f.

6

Anton Kippenberg to the Leipzig Police Authority, 25th September 1934, GSA Weimar, 50/3.

7

Salzer 1934.

8

Zweig F 1947, p 374.

9

19th January 1935, Zweig GW Tagebücher, p 366 f.

10

Stefan Zweig to Karl Geigy-Hagenbach, 9th March 1935, ÖUB Basle.

11

Geiger 1958a, p 235 ff.

12

Zuckmayer 2006, p 62.

13

Geiger 1958b, p 423. The original is in Italian.

14

Zweig GW Gedichte, p 225 ff.

15

As quoted in Geiger 1958b, p 424.

16

Thomas Mann to Agnes E Meyer, 25th February 1942. In: Briefwechsel Mann/Meyer, p 375.

17

Stefan Zweig to Oskar Maurus Fontana, undated, but later than 25th December 1926. In: Briefe III, p 177 f.

18

TM Tagebücher 1935–1936, entry for 26th May 1935, p 109.

19

Stefan Zweig to Karl Geigy-Hagenbach, 24th December 1934, ÖUB Basle.

20

Katharina Kippenberg to Stefan Zweig, 27th June 1935, SUNY, Fredonia/NY.

21

Ebermayer 2005, p 277.

22

Stefan Zweig to Karl Geigy-Hagenbach, 5th September 1935, ÖUB Basle.

23

Stefan Zweig to Romain Rolland, 7th January 1936. In: Briefwechsel Rolland, Vol 2, p 616 f.

24

20th August 1936, Zweig GW Tagebücher, p 399.

25

21st August 1936, Zweig GW Tagebücher, p 399 f.

26

Zweig GW Brasilien, p 251.

27

Stefan to Friderike Zweig, 3rd September 1936. In: Briefwechsel Friderike Zweig 1951, p 300.

28

Stefan to Friderike Zweig, 25th August 1936, SUNY, Fredonia/NY.

29

Stefan to Friderike Zweig, 26th August 1936. In: Briefwechsel Friderike Zweig 2006, p 307 f.

30

Stefan to Friderike Zweig, 12th September 1936. In: Briefwechsel Friderike Zweig 2006, p 309 f.

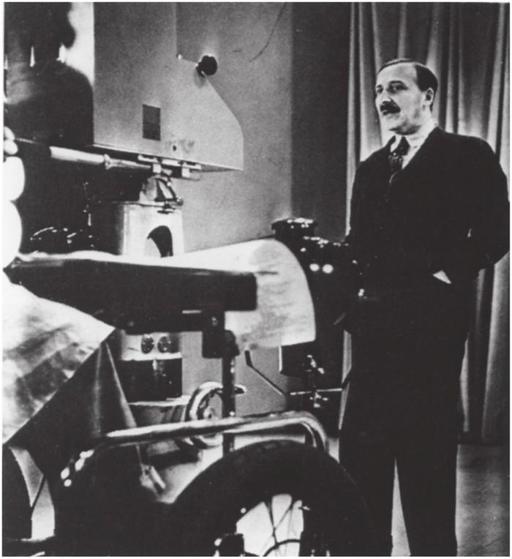

Stefan Zweig during his television interview with the BBC

Nobody in their wildest dreams would think that today is the day when the greatest catastrophe in the history of mankind began! How different from the days in Austria—when people went around bawling their heads off, drunk with elation and beer. But that was a generation that knew nothing of war, that had romantic ideas about it, and believed (like my own father) that a war would last just a matter of weeks, and that everything would go on just as before when it was over.

1

Diary 1st September 1939

“T

OMORROW THEY HAVE LINED ME UP

for a five-minute interview on the ‘television’”, wrote Zweig to his wife in the summer of 1937, “it will be quite amusing to learn how one talks to invisible people who can see me.”

2

All his fulmination about the “Radioten” in Salzburg was now forgotten—in London they had been experimenting successfully for a number of years now with a new medium: television. The BBC had officially begun broadcasting in November 1936, and just a few months later, on 23rd June 1937, Zweig went to the studios in Alexandra Palace to give his first, and as far as we know his only, television interview. In the programme

Picture Page

, which was broadcast in the afternoon between 3.30 and 4.00 pm, Zweig was asked a series of questions by Leslie Mitchell, one of the icons of the new medium. Everything had been discussed in great detail beforehand and rehearsed, of course. No pictures or sound were recorded, but the text of the interview survives in a transcript:

LESLIE MITCHELL

:

I hear, Mr Zweig, that you are not merely a visitor to London, but that you have decided to settle here with us more or less permanently?

STEFAN ZWEIG

:

Yes, that is so. I plan to spend seven or eight months in London each year. The rest of the time I am travelling. For instance, last year I was in South America, Brazil and the Argentine. But it is in London that I like to work. It is such an excellent city for an author to live in.

LESLIE MITCHELL

:

You mean from the point of view of work? Why do you like it so particularly?

STEFAN ZWEIG

:

I find it the ideal city for three reasons. For one thing, you have here the best libraries—the British Museum, the London Library and so on. Then too London is becoming the capital of music. And thirdly, one may work here completely undisturbed. There is none of that tense atmosphere which is to be found in so many big cities today. In London I have discovered it is possible for an individual to fashion his life in his own way, undisturbed by the intrusions of other people. (

Emphatically

) It is possible to be alone, and that is a liberty of tremendous importance to the creative artist.

LESLIE MITCHELL

:

I’m glad you find it so pleasant here, Mr Zweig … By the way, is this the first time you have come to England?

STEFAN ZWEIG

:

Oh no. My first visit was as a student, thirty years ago, when I was specially interested in William Blake and in English literature. I was determined to come back again eventually, and (

smiling

) here I am you see. [ … ]

LESLIE MITCHELL

:

Are you planning any other books at the moment?

STEFAN ZWEIG

:

Beside the biography I have been working recently on a new novel and also on another non-fiction book to be published next year.

LESLIE MITCHELL

:

Three books at once! That’s pretty good going … Perhaps you would tell us something about the others you are writing. For instance, what is the title of the novel?

STEFAN ZWEIG

:

In German, “

Mord durch Mitleid

”. You might translate it as “Murder by Kindness” or “Murder by Compassion”.

LESLIE MITCHELL

:

(

Laughingly

) Don’t tell me you are turning to detective fiction, Mr Zweig!

STEFAN ZWEIG

:

(

Also amused

) No indeed. You must not be misled by my title. Actually the book is a contemporary psychological study, in the setting of

Vienna, and in it I tackle for the first time some quite new medical problems. [ … ]

LESLIE MITCHELL

:

I believe it is correct to say that you are one of the world’s most translated authors—isn’t that so, Mr Zweig? Is there any language into which your work has not been transcribed?

STEFAN ZWEIG

:

(

With amused diffidence

) Well, I don’t know whether the Tibetans have shown any interest in me yet!

3

As the attached programme note reveals, Zweig went home with a payment of “Two guineas [ … ] for interview as Austrian Author”.

4

As interesting as this experience of television had been, he did feel that interviews of this sort were rather too lightweight. In December he was asked by the BBC if he was available for a radio interview. Lotte Altmann replied on his behalf, saying he was not at all keen on being involved in short broadcasts, where he would not have time to make more than one or two serious points. In the coming months various possibilities for a longer programme were explored. Among the proposals that were worked up were a feature on his tragicomedy

Das Lamm des Armen

and readings from other works of his; but it seems, from the available documentary evidence, that these plans were soon shelved.