Through the Language Glass: Why the World Looks Different in Other Languages (5 page)

Read Through the Language Glass: Why the World Looks Different in Other Languages Online

Authors: Guy Deutscher

Tags: #Language Arts & Disciplines, #Linguistics, #Comparative linguistics, #General, #Historical linguistics, #Language and languages in literature, #Historical & Comparative

LANGUAGE MIRROR

1

London, 1858. On the first of July, the Linnean Society, in its magnificent new quarters at Burlington House in Piccadilly, will hear two papers by Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace announcing jointly a theory of evolution by natural selection. Before long, the flame will flare up and illuminate the intellectual firmament, leaving no corner of human reason untouched. But although the wildfire of Darwinism will catch up with us soon enough, we do not begin quite there. Our story starts a few months earlier and a few streets away, in Westminster, with a rather improbable hero. At forty-nine, he is already an eminent politician, member of Parliament for Oxford University, and ex-chancellor of the Exchequer. But he is still ten years away from becoming prime minister, and even further from being celebrated as one of Britain’s greatest statesmen. In fact, the Right Honorable William Ewart Gladstone has been languishing on the opposition benches for the last three years. But his time has not been idly spent.

While out of office, he has devoted his legendary energies to the realm of the mind, and in particular to his burning intellectual passion: that ancient bard who “founded for the race the sublime office of the

poet, and who built upon his own foundations an edifice so lofty and so firm that it still towers unapproachably above the handiwork not only of common, but even of many uncommon men.” Homer’s epics are for Gladstone nothing less than “the most extraordinary phenomenon in the whole history of purely human culture.” The

Iliad

and the

Odyssey

have been his lifelong companions and his literary refuge ever since his Eton schooldays. But for Gladstone, a man of deep religious conviction, Homer’s poems are more than merely literature. They are his second Bible, a perfect compendium of human character and experience that displays human nature in the most admirable form it could assume without the aid of Christian revelation.

Gladstone’s monumental oeuvre, his

Studies on Homer and the Homeric Age

, has just been published this March. Its three stout, door-stopping tomes of well over seventeen hundred pages sweep across an encyclopedic range of topics, from the geography of the

Odyssey

to Homer’s sense of beauty, from the position of women in Homeric society to the moral character of Helen. One unassuming chapter, tucked away at the end of the last volume, is devoted to a curious and seemingly marginal theme, “Homer’s perception and use of color.” Gladstone’s scrutiny of the

Iliad

and the

Odyssey

revealed that there is something awry about Homer’s descriptions of color, and the conclusions Gladstone draws from his discovery are so radical and so bewildering that his contemporaries are entirely unable to digest them and largely dismiss them out of hand. But before long, Gladstone’s conundrum will launch a thousand ships of learning, have a profound effect on the development of at least three academic disciplines, and trigger a war over the control of language between nature and culture that after 150 years shows no sign of abating.

Even in a period far less unaccustomed than ours to the concurrence of political power and greatness of mind, Gladstone’s Homeric scholarship was viewed as something out of the ordinary. He was, after all, an active politician, and yet his three-volume opus would have been no mean achievement as the lifetime’s work of a dedicated don. To some, especially political colleagues, Gladstone’s devotion to the classics was the cause of resentment. “You are so absorbed in questions about Homer and Greek words,” a party friend complained, “that you are not reading newspapers or feeling the pulse of followers.” But for the general public, Gladstone’s virtuoso Homerology was a subject of fascination and admiration. The

Times

ran a review of Gladstone’s book that was so long it had to be printed in two installments and would amount to more than thirty pages in this book’s type. Nor did Gladstone’s erudition fail to impress in intellectual circles. “There are few public men in Europe,” was one professor’s verdict, “so pure-minded, so quick-sighted, and so highly cultivated as Mr. Gladstone.” In the following years, books by distinguished academics in Britain and even on the Continent were dedicated to Gladstone, “the statesman, orator, and scholar,” “the untiring promoter of Homeric Studies.”

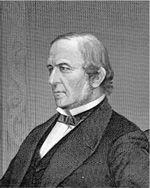

William Ewart Gladstone, 1809–1898

Of course, there was a but. While Gladstone’s prodigious learning, his mastery of the text, and his fertility of logical resources were universally praised, the reaction to many of his actual arguments was downright scathing. Alfred Lord Tennyson wrote that on the subject of Homer “most people think [Gladstone] a little hobby-horsical.” A professor of Greek at Edinburgh University explained to his students that “Mr. Gladstone may be a learned, enthusiastic, most ingenious and subtle expositor of Homer—always eloquent, and sometimes brilliant; but he is not sound. His logic is feeble, almost puerile, his tactical movements, though full of graceful dash and brilliancy, are utterly destitute of sobriety, of caution,

and even of common sense.” Karl Marx, himself an avid reader of Greek literature and not one to mince his words, wrote to Engels that Gladstone’s book was “characteristic of the inability of the English to produce anything valuable in Philology.” And the epic review in the

Times

(anonymous, as reviews were in those days) twists itself into the most convoluted of circumlocutions to avoid explicitly calling Gladstone a fool. It starts by declaring that “Mr. Gladstone is excessively clever. But, unfortunately for excessive cleverness, it affords one of the aptest illustrations of the truth of the proverb that extremes meet.” The review ends, nearly thirteen thousand words later, with the regret that “so much power should be without effect, that so much genius should be without balance, that so much fertility should be fertility of weeds, and that so much eloquence should be as the tinkling cymbal and the sounding brass.”

What was so wrong with Gladstone’s

Studies on Homer

? For a start, Gladstone had committed the cardinal sin of taking Homer far too seriously. He was treating Homer “with an almost Rabbinical veneration,” snorted the

Times

. In an age that prided itself on its newly discovered skepticism, when even Holy Scripture’s authority and authorship were beginning to yield to the scalpel of German textual criticism, Gladstone was marching to the beat of a different drum. He dismissed out of hand the theories, much in vogue at the time, that there had never been a poet called Homer and that the

Iliad

and the

Odyssey

were instead a patchwork of a great number of popular ballads cobbled together from different poets over many different periods. For him, the

Iliad

and the

Odyssey

were composed by a single poet of transcendental genius: “I find in the plot of the

Iliad

enough beauty, order, and structure to bear an independent testimony to the existence of a personal and individual Homer as its author.”

Even more distasteful to his critics was Gladstone’s insistence that the story of the

Iliad

was based on at least a core of historical fact. To the enlightened academics of 1858, it seemed childishly credulous to assign any historical value to a story of a ten-year Greek siege of a town called Ilios or Troia, following the abduction of a Greek queen by the Trojan prince Paris, also known as Alexandros. As the

Times

put it, these tales were “accepted by all mankind as fictions of very nearly the same order

as the romances of Arthur.” Needless to say, all this was twelve years before Heinrich Schliemann actually found Troy on a mound overlooking the Dardanelles; before he excavated the palace of Mycenae, homeland of the Greek overlord Agamemnon; before it became clear that both Troy and Mycenae were rich and powerful cities at the same period in the late second millennium

BC

; before later excavations showed that Troy was destroyed in a great conflagration soon after 1200

BC

; before sling stones and other weapons were found on the site, proving that the destruction was caused by an enemy siege; before a clay document was unearthed that turned out to be a treaty between a Hittite king and the land of Wilusa; before the same Wilusa was securely identified as none other than Homer’s Ilios; before a ruler of Wilusa whom the treaty calls Alaksandu could thus be related to Homer’s Alexandros, prince of Troy; before—in short—Gladstone’s feeling that the

Iliad

was more than just a quilt of groundless myths turned out to have been rather less foolish than his contemporaries imagined.

There is one area, however, where it is difficult to be much kinder to Gladstone today than his contemporaries were at the time: his harping on about Homeric religion. Gladstone’s was neither the first nor the last of great minds to be led astray by religious fervor, but in the case of his

Studies on Homer

, his convictions took the particularly unfortunate turn of trying to marry Homer’s pagan pantheon with the Christian creed. Gladstone believed that at the beginning of mankind humanity had been granted a revelation of the true God, and while knowledge of this divine revelation later faded and was perverted by pagan heresies, traces of it could be detected in Greek mythology. He thus left no god unturned in his effort to detect Christian truth in the Homeric pantheon. As the

Times

put it, Gladstone “strained all his faculties to detect, in the Olympian Courts, the God of Abraham who came from Ur of the Chaldees, and the God of Melchezedek who dwelt in Salem.” Gladstone argued, for instance, that the tradition of a Trinity in the Godhead left its traces on the Greek mythology and is manifested in the three-way division of the world between Zeus, Poseidon, and Hades. He claimed that Apollo displays many of the qualities of Christ himself and even went so far as to suggest that Apollo’s mother, Leto, “represents the

Blessed Virgin.” The

Times

was not amused: “Perfectly honest in his intentions, he takes up a theory, and no matter how ridiculous it is in reality, he can make it appear respectable in argument. Too clever by half!”

Gladstone’s determination to baptize the ancient Greeks did his

Studies on Homer

a sterling disservice, since his religious errings and strayings made it all too easy to discount his many other ideas. This was most unfortunate, because when Gladstone was not calculating how many angels could dance on the tip of Achilles’ spear, it was exactly his other alleged great failing, that of taking Homer too seriously, that elevated him far above the intellectual horizon of most of his contemporaries. Gladstone did not believe that Homer’s story was an accurate depiction of historical events, but unlike his critics he understood that the poems held up a mirror to the knowledge, beliefs, and traditions of the time and were thus a historical source of the highest value, a treasure-house of data for the study of early Greek life and thought, an authority all the more trustworthy because an unconscious authority, addressing not posterity but Homer’s own contemporaries. Gladstone’s toothcombing analysis of what the poems said and—sometimes even more importantly—what they did not say thus led him to remarkable discoveries about the cultural world of the ancient Greeks. The most striking of these insights concerned Homer’s language of color.

For someone used to the doldrums and ditchwater of latter-day academic writing, reading Gladstone’s chapter on color comes as rather a shock—that of meeting an extraordinary mind. One is left in awe by the originality, the daring, the razor-sharp analysis, and that breathless feeling that however fast one is trying to run through the argument in one’s own mind, Gladstone is always two steps ahead, and, whatever objection one tries to raise, he has preempted several pages before one has even thought of it. It is therefore all the more startling that Gladstone’s tour de force comes to such a strange conclusion. To phrase it somewhat anachronistically, he argued that Homer and his contemporaries perceived the world in something closer to black and white than to full Technicolor.