Through the Storm

| Through the Storm |

| Unknown |

| (2012) |

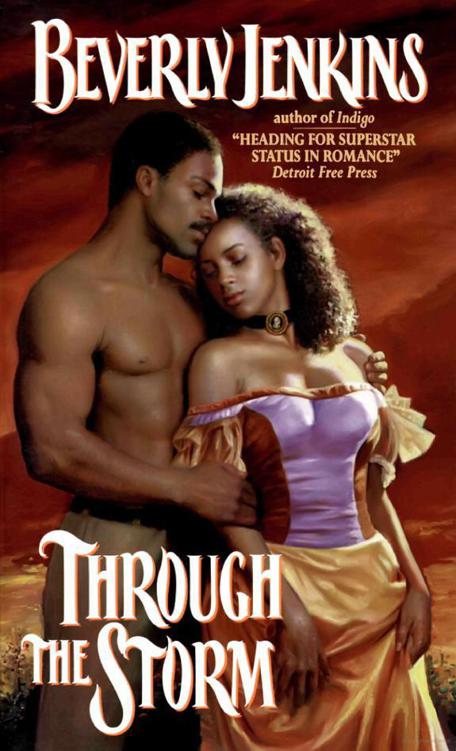

THROUGH THE STORM

BEVERLY JENKINS

This book is dedicated to Christine Zika—

remember to allow yourself joy

.

And to Alex—because he is always there

.

Now rally, Black Republicans

Wherever you may be

Brave soldiers on the battle-field

And sailors on the sea.

Now rally, Black Republicans—

Aye rally! We are free!

We’ve waited long long

To sing the song—

The song of liberty.

“

The Song of the Black Republicans

”

The Black Republican,

New Orleans

April 29, 1865

Contents

When house slave Sable Fontaine was growing up in the…

Staying off the road, Sable used the trees and thick…

Major Raimond LeVeq put down his pen and stretched wearily.

Mrs. Reese and the other laundresses greeted Sable’s return warmly.

As she entered the tent, Sable heard, “You’re back awfully…

After the yard cleared and Borden stormed away, Sable walked…

“How many more?” Raimond asked Andre as he scribbled his…

Sable looked out at the gray March day and yearned…

By week’s end, Sable had disposed of the last of…

The next morning, Sable awakened still close to Raimond’s side.

That evening, Drake and Beau came to dine with Juliana…

Riding home in a hack they had hailed outside Archer’s…

Like everyone else, Sable was stunned by Circular 15. Obviously…

Louisiana’s long-anticipated Radical Convention convened two days later. Raimond had…

They spent the remainder of their holiday in a beautiful…

Sable and her children had been in Paradise for over…

Other Books by Beverly Jenkins

Epigraph

Now rally, Black Republicans

Wherever you may be

Brave soldiers on the battle-field

And sailors on the sea.

Now rally, Black Republicans—

Aye rally! We are free!

We’ve waited long long

To sing the song—

The song of liberty.

“

The Song of the Black Republicans

”

The Black Republican,

New Orleans

April 29, 1865

Georgia, 1864

W

hen house slave Sable Fontaine was growing up in the mansion that was her home, it had taken fifteen male slaves to care for the rolling green lawns surrounding the estate. Under the watchful eye of the head gardener, an equal number of young slaves had trimmed the trees and sculpted the shrubs. They’d planted lush, fragrant flowers every spring, adding color and beauty to the genteel, pastoral surroundings, and every year the sprawling white house had been freshly painted so that its stately columns anchoring the wide front porch stood like monuments gleaming in the Georgia sun.

Now the Fontaine lawns and gardens were overgrown with weeds. No one had trimmed the shrubs or trees in three seasons, and the lush flowers hadn’t been planted for years. The house hadn’t been painted either, and it gleamed no more. Because of Mr. Lincoln’s war, no slaves could be spared to perform such inconsequential tasks. Everyone was too bent upon survival.

When the conflict began, no one imagined the war would drag on for years or that families in the South would be reduced to living no better than their slaves. The thought that there would be food riots in Charleston

and Mobile, or that the Southern way of life would be destroyed, had been unthinkable. The South’s sons and fathers rode off to war in 1861 filled with the pride and arrogance of their class. It was now 1864, and the prideful and the arrogant were deserting in staggering numbers, weary of fighting, starving, and dying. Adding to the turmoil were huge numbers of escaping slaves—men, women, and children who weren’t waiting for the yoke of enslavement to be officially lifted. They were slipping away all over the south, many attaching themselves to the advancing Union troops. Sable’s great-aunt Mahti said you could smell freedom in the air.

For Sable, though, the long anticipated, sweet scent of freedom had become fouled. Even as the marauding Yankees marched deeper and deeper into the heartland, tearing up the railroads and forcing families to flee, the buying and selling of slaves continued. Yesterday, she’d been sold too.

Some would say a twenty-nine year old female slave should be flattered to fetch the comely sum of eight hundred dollars, especially with war on, but Sable felt no such pride. The buyer, a man named Henry Morse, would not treat her well.

Sable’s mistress, Sally Ann Fontaine, had announced the sale at supper last evening. Sable had stared at her in disbelief. Her anger flared as she held Sally’s triumphant eyes, but Sable knew her feelings would make no difference. In the end only numbness remained, a numbness that gripped her still.

Now, watching the sun set, Sable stood on the wide front porch contemplating her future. She felt someone step out onto the porch behind her and knew without turning that it was Mavis.

“How are you, little sister?” Mavis asked softly.

In spite of Sable’s mood, the salutation made her smile. The half-sisters had been born less than six minutes apart and Mavis never let Sable forget who’d drawn breath first. Sable’s love for her knew no bounds,

but contemplating Mavis’s query made the numbness return. “As well as can be expected, I suppose. How about you?”

Sable turned and peered into the face that in many ways mirrored her own. Mavis’s brown eyes were redrimmed and swollen as she confessed, “I can’t stop crying.”

Sable turned away. She ached too but knew tears were a waste of time; they would not alter her fate.

Mavis announced bitterly, “I told Mama I’ll never speak to her again if she goes through with the sale, but she won’t change her mind.”

Sable didn’t expect Sally Ann to relent. The mistress of the household had never hidden her dislike for Sable, mostly because of what the bronze-skinned, green-eyed Sable represented. Sable’s mother, a slave woman named Azelia, had given birth to Sable six minutes after Sally Ann gave birth to Mavis. Both baby girls had been fathered by Sally Ann’s husband, Carson Fontaine, just as he’d fathered Sable’s older brother Rhine and Mavis’s brother Andrew, two years earlier.

Mavis interrupted Sable’s thoughts. “I’ll help however I can.”

Sable knew she would. Though society forced the two women to walk in different worlds—making one mistress and the other slave—they’d shared everything all their lives. When Mavis had lost her beloved husband, Sanford, six months into the war, Sable had held her while she cried.

Mavis stepped around to look into Sable’s eyes, “I know you’re thinking of running, but there must be another way. The roads aren’t safe.”

“Safer than having Henry Morse as a master?” Sable retorted.

Rumors surrounding Morse’s treatment of his female slaves linked him to at least two mysterious deaths that had taken place last year. The local constabulary had eventually charged a young male slave on a neighboring

plantation with the killings, but most people, Black and White, questioned the validity of the official findings. The slave had been hanged as punishment, in spite of protestations from his owner, who’d loudly proclaimed his man’s innocence.

Mavis spoke again. “Well, if you do decide to run, don’t worry. I’ll make certain Mahti’s cared for.”

In spite of Mavis’s assurances Sable did worry. Since receiving Sally Ann’s news, the fate of Sable’s great-aunt had been weighing heavily on Sable’s already over-burdened shoulders.

Mahti had been captured by European slavers and brought to America at the tender age of eight. Now, over sixty years later, she appeared destined to die without ever seeing her homeland again. She’d been ill for some time and although Sable knew Mavis would do everything in her power to make Mahti comfortable until the end, Sable could not leave her; it would break her heart. Were Sable’s brother Rhine there, maybe the two of them could concoct a plan to secure Mahti’s safety, but two years ago Rhine had gone to war to serve as personal valet to Andrew, Mavis’s older brother. No one had heard a word from either man since then.

So Mahti’s future remained unsettled. Sable didn’t want her aunt to die without a final farewell caress from Sable’s hand to ease the passage home. Six weeks ago, she’d been given a chance to escape with the Fontaine’s head butler and driver, Otis, but she’d declined because of Mahti’s health. Otis had forged himself a pass, “borrowed” the last working carriage the Fontaines owned, and driven himself to freedom. With him he’d taken his wife Opal, who’d been the Fontaines’ cook and head housekeeper for over thirty years, and their fifteen-year-old daughter Ophelia, the kitchen maid. Sally Ann had thrown a fit upon finding them gone, but Sable had smiled inwardly, hoping they’d reached freedom safely.

Sable had been a slave all her life and dearly wanted

to be free, but she wouldn’t leave unless she could take her aunt too.

Sable’s face took on a distinct show of dislike as Henry Morse’s fancy black carriage drew up in front of the house. As he got out and headed up the long winding walk toward the porch, Mavis drawled brittlely, “Two years ago, trash like him wouldn’t’ve had the gall to call at the front door.”

Sable agreed. Like Black women all over the South, the Fontaines’ housekeeper Opal had set very high standards of etiquette for family and visitors alike. A man of Morse’s pedigree and reputation would never have set foot in her parlor. He’d have been received at the back door or not at all. Times were different now. With everyone in the South, Black and White, starving and clad in rags, the prewar caste system had been turned upside down. While the scions of the first families were on the front lines fighting and dying to preserve their way of life, back home men of questionable motives and character were forming a new class of Southern aristocracy. If the rumors were true, Morse had made a fortune over the past few years by buying up the property and slaves of planters who chose to flee the South in advance of the Yankees. Families who’d once shunned him because of his dirt-poor beginnings were now inviting him into their homes, in case they needed to make similar deals.