Thrush Green (18 page)

Authors: Miss Read

Tags: #Country life, #Pastoral Fiction, #Thrush Green (Imaginary Place), #England, #Fiction

Still laughing, he left her standing in the sunshine and ran lightly around the caravan and up the steps.

The scene that met Ben's astonished gaze needed no explanation. After the dazzle outside, the interior of Mrs. Curdle's caravan was murky, but Ben saw enough to justify his swift action.

The bunk bed lay tumbled, and upon the crumpled quilt was the Curdle Bank. The lid of the battered case was open, displaying a muddle of bank notes and silver and copper coins.

Sam, on being disturbed, had cowered as far as he could into a corner by the glittering stove. One hand he held up as if to ward off a blow, and the other was hidden behind his back.

His eyes were terrified as he gazed at the intruder who barred his only way of escape. His mouth dropped open, and a few incoherent bubbling sounds were the nearest that he could get to speech. Not that he was given time to account for himself, for Ben was upon him in a split second, gripping his arms painfully.

Sam twisted and heaved this way and that, trying to hide the notes in his hand, but Ben jerked his arm viciously behind him, and turned him inexorably toward the light. The notes fluttered to the floor.

Ben gave a low animal growl of fury and Sam a shrill scream of sudden pain. He lunged sharply with his knee. The two men parted for a moment, then turned face to face, and, locked in a terrible panting embrace, began to wrestle, one desperate with fear and the other afire with fury.

They lurched and thudded this way and that within the narrow confines of Mrs. Curdle's home. Ben's shoulder brought down half a dozen plates from the diminutive dresser. Sam's foot jerked a saucepan from the hob, and the hissing water added its sound to the clamor which grew as the fight grew more vicious.

Molly, aghast at the noise, ran to see what was happening, and, appalled at the sight, fled to get help. The flaxen-haired girl, still holding the baby to her breast, was wandering toward her.

"It's a fight!" gasped Molly. The girl looked mildly surprised, but uttered no word, merely continuing in an unhurried manner, to approach the source of the uproar.

Molly ran around a stall and was amazed to see a number of the Curdles converging rapidly upon her. There were about a dozen altogether, including several young children, whose eyes were alight with pleasurable anticipation at the thought of witnessing a fight.

The bush telegraph of the fairground was in action. These first spectators hurried past Molly, and, in the distance, she could see others, jumping down the steps of their caravans, calling joyously to each other of this unlooked-for excitement and scurrying to swell the crowd which was fast collecting around Mrs. Curdle's caravan.

Emerging from one of the tents Molly saw the great lady herself. A small fair-haired girl tugged agitatedly at her hand, urging her to hurry. The old lady's face was grim. She bore down upon the shrinking Molly like some majestic ship, and passed her without even noticing the trembling girl.

Emboldened by the example of this dominating head of the tribe, Molly braced herself, and like a small dinghy following in the wake of a liner she crept after Ben's grandmother and back to the scene of battle.

The spectators, who had been vociferous, quieted as their leader stalked into their midst.

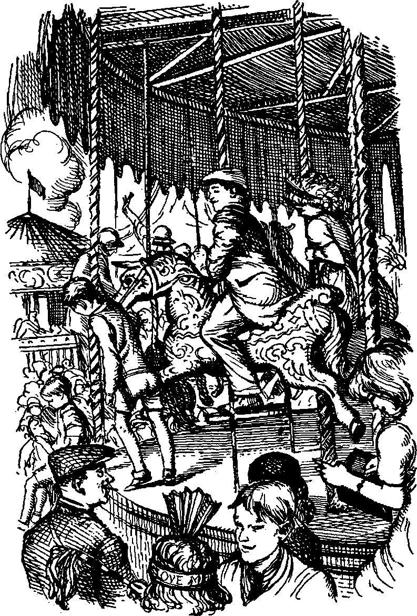

It was a tense moment. Ben had forced Sam to the doorway and they grappled and swayed dangerously at the head of the steps. They made a wild and terrifying sight, bloodied and disheveled.

There was sudden convulsive movement, a sickening crack as Sam's jaw and Ben's bony fist met, and Sam fell bodily backward to the grass. He rolled over, scattering some of the crowd, groaned, twitched, and lay still.

A great sigh rippled around the onlookers, like the sound of wind through corn, and Mrs. Curdle strode to the foot of the steps. She spared no glance for the prostrate man at her feet, but looked unblinkingly at Ben, who swayed, bruised and dizzy, against the door frame. A trickle of blood ran across his swelling cheek, and blood dripped from his broken knuckles upon the dusty black corduroy trousers.

Nobody watching the old lady could guess her feelings. Her dusky face was inscrutable, her mouth pressed into a hard thin line. Ben looked down upon her forlornly and broke the heavy silence.

"He asked for it, Gran," he said apologetically.

Mrs. Curdle made no sign, but her heart melted at the words. Just so, she remembered, had George looked, so many, many years ago, when she had caught him fighting another six-year-old. He too had swayed on his feet, and had looked outwardly contrite, while all the time, as she very well knew, he had secretly gloried in his victory. The sudden memory stabbed her so sharply, and filled her with such mingled sorrow and pride, that she continued to gaze at George's son (who might be George himself, so dearly did she love him), in utter silence.

Ben's eyes met his grandmother's and in that long shared look he knew what lay in her heart. He had proved himself; and to that love which she had always borne him another quality had been added. It was reliance upon him, and Ben rejoiced that it was so.

"Gran!" he cried, descending the steps with his arms outstretched. But the old lady shook her head and turned to face the crowd. And Ben, content with his new knowledge, waited patiently behind her.

It was at this moment that Bella and her three children came upon the scene. She had been told the news as she struggled up the hill from Lulling, and now arrived, screaming, breathless and blaspheming, her yellow hair streaming in the breeze, like some vengeful harpy. At the sound of her voice, Sam groaned, and struggled into a sitting posture, his aching head supported by his battered fists.

Mrs. Curdle raised her ebony stick and Bella's torrent of abuse slowed down. Beneath the old lady's black implacable silence she gradually faltered to a stop, and began to weep instead, the three children adding their wails to their mother's.

At last the old lady spoke, and those who heard her never forgot those doom-laden words. Thunder should have rolled and lightning flashed as Mrs. Curdle drew herself up to her great height, and pointing the ebony stick at Sam, spoke his sentence.

"You and yours," she said slowly, each word dropping like a cold stone, "go from here tomorrow. And never, never come back!"

She turned her solemn gaze upon the gaping crowd, and, with a flick of the ebony stick, dismissed them. Two men assisted Sam to his feet and amidst lamentations from his family he hobbled to his caravan.

Mrs. Curdle watched the rest of the tribe melt away and turned to question Ben at the foot of the steps.

But Ben was not there. She looked sharply about, trying to catch sight of him among the departing spectators, and suddenly saw him. He was some distance off, talking earnestly to a pretty young girl, beneath a tree.

As Mrs. Curdle watched, she saw him take the girl's hand. They advanced toward her, the girl looking shy and hanging back. But there was nothing shy about Ben, thought Mrs. Curdle, shaken with secret laughter and loving pride.

For, bruised and bloody, torn and dusty as he was, Ben radiated supreme happiness as he limped toward her across Thrush Green; and Mrs. Curdle rejoiced with him.

PART THREE

Night

13. Music on Thrush Green

T

HE SUN

was beginning to dip its slow way downhill, to hide, at last, behind the dark mass of Lulling Woods.

The streets of Lulling still kept their warmth, and the mellow Cotswold stone of the houses glowed like amber as the rays of the sun deepened from gold to copper.

On Thrush Green the chestnut trees sloped their shadows toward Dr. Bailey's house. The great bulk of the church was now in the shade, crouching low against the earth like a massive mother hen. But the weathercock on St. Andrew's lofty steeple still gleamed against the clear sky, and from his perch could see the river Pleshy far below, winding its somnolent way between the water meadows and reflecting the willows and the drinking cattle which decorated its banks.

Although twilight had not yet come the lights of the fair were switched on at a quarter past six, and the first strains of music from the roundabout spread the news that Mrs. Curdle's annual fair was now open.

The news was received, by those who heard it on Thrush Green, in a variety of ways. Sour old Mr. Piggott, who had looked in at St. Andrew's to make sure that all was in readiness for the two churchings at six-thirty, let fall an ejaculation quite unsuitable to its surroundings, and emerging from the vestry door, crunched purposefully and maliciously upon a piece of coke to relieve his feelings.

Ella Bembridge, who had eaten a surprisingly substantial tea for one suffering from burns, shock and a rash, groaned aloud and begged Dimity to close the window against "that benighted hullabaloo." Dimity had done so and had removed the patient's empty tray, noting with satisfaction that she had finished the small pot of quince jelly sent by Dotty Harmer that afternoon. In the press of events, she had omitted to tell Ella of Dotty's kindness, and now, seeing the inroads that her friend had made into Dotty's handiwork, she decided not to mention it. Ella could be so very scathing about Dotty's cooking, thought Dimity, descending the crooked stairs, but obviously the quince jelly had been appreciated.

Paul, beside himself with excitement, was leaping up and down the hall, singing at the top of his voice. Occasionally he broke off to bound up to Ruth's bedroom, where she was getting ready. The appalling slowness with which she arranged her hair and powdered her face drove her small nephew almost frantic. This was the moment he had been waiting for all day—for weeks—for a whole year! Would she

never

be ready?

To young Dr. Lovell, returning from a visit to Upper Pleshy in his shabby two-seater, the color and glitter of the fair offered a spectacle of charming innocence. Here was yet another aspect of Thrush Green to increase his growing affection for the place. Throughout the day he had found himself thinking of his happiness in this satisfying practice. He could settle here so easily, he told himself, slipping into place among the friendly people of Lulling, enjoying their company and sharing their enchanting countryside.

He drew up outside Dr. Bailey's house, and resting his arms across the steering wheel, watched the bright scene with deep pleasure. This was the first time he had seen Mrs. Curdle's fair. It would probably be the only time, he told himself grimly, for Mrs. Curdle might not return next year, and if she did, who was to know where he would be?

The thought was so painful that Dr. Lovell jerked his long legs out of the car, slammed the door and moved swiftly toward the surgery to find solace in his work.

Mrs. Bailey heard the familiar noise of the surgery door, and looked over the top of her spectacles, just in time to see young Dr. Lovell vanish inside.

She was sitting in the window seat, sewing, and enjoying the last rays of the sunshine which had transfigured the whole day.

Dr. Bailey lay comfortably on the couch attempting to solve

The Times

crossword which lay upon his bony knees. He had recovered from his afternoon's bout of weakness and, to his wife's discerning eye, he appeared more serene and confident than he had for many weeks—as indeed he was. For having resolved to offer young Lovell a partnership in the practice, his mind was at rest. That agonizing spasm in the brilliant sunshine of Thrush Green had taught him a sharp lesson and he was a wise enough man to heed it.

His decision made, at terms with himself and the world, the old doctor was content to let his body and mind relax, awaiting the end of the surgery hours when he could put his proposal to his new young helper. That he would accept it, Dr. Bailey had no doubt at all.

The room had been quiet, with that companionable silence born of mutual ease. When the music of the fair blared out it made no difference to the peace of the two listeners. It was the first of May on Thrush Green, and music was its right and fitting accompaniment.

It was also the overture to Mrs. Curdle's annual visit, remembered Mrs. Bailey. She let her needlework drop into her lap and looked at last year's bunch of wood-shaving flowers which she had conscientiously put into a tall vase ready for Mrs. Curdle's polite inspection later.

Her mind flew back to her first view of young Mrs. Curdle, with baby George securely fastened to her hip by an enveloping bright shawl, holding the first of many mammoth bouquets. Poor George, thought Mrs. Bailey, so loved, so dear, so soon to leave his adoring mother to be killed in battle. What a tragic loss, not only for inconsolable Mrs. Curdle, but for their fair and, for that matter, the country as a whole.

Mrs. Bailey's thoughts slipped back, as they so often did, to those lost young friends of both wars, and she wondered, yet again, if the world would have been different had they lived. It would have been enriched, of that she had no doubt, for all those lives had something of value—some facet of truth and beauty—to offer, that would have illumined other men's lives as well as their own. The world we must accept as it is, she recognized that fact philosophically, but it did not stop one from pondering on its limitless possibilities if those others, untimely dead, had had their way with it.