Thug: The True Story Of India's Murderous Cult (33 page)

Read Thug: The True Story Of India's Murderous Cult Online

Authors: Mike Dash

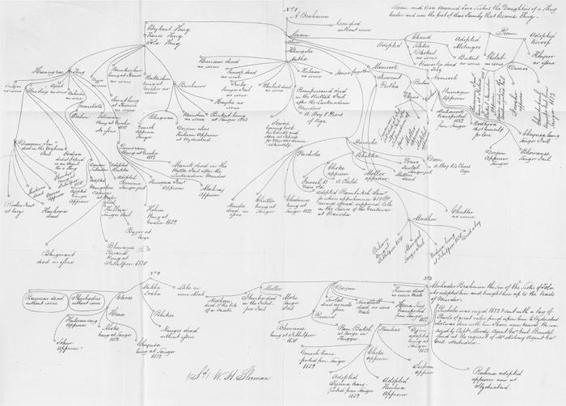

Sleeman’s genealogies nonetheless impressed Francis Curwen Smith, who saw in them not only confirmation that the most important Thugs were stranglers by birth, but also a useful tool to assess the statements of approvers. The trees could be used, for example, to place an informant within his extended family and thus deduce which Thugs he might favour or attempt to gloss over in his testimony. And ‘they show,’ Smith added,

the connection of the families of the principal Thugs committed for trial since 1830 with the Sindhousee (hereditary) Thugs. The tables were revised by Captain Sleeman often in the presence of the members of the different families … and the tables of their respective families have been

acknowledged

by them to be correct, though framed from information derived from members of opposite parties.

It was not long, then, before the pedigrees became another weapon in the Company’s war against the stranglers – ‘a blue-print, as it were, of everyone, Muslim and Hindu, linked with Thuggee by blood’. Used in conjunction with the Thug register, they enabled Sleeman and his assistants to note the fate of every known strangler and to keep track of those who remained at large. The results of their plodding clerical work were brandished, almost as trophies, in Thuggy Department papers: evidence – so it appeared – that every last Thug had been named, numbered and accounted for.

*

‘There is,’ William Sleeman once observed, ‘one truth that cannot be too often repeated: that if we wish to suppress the system [of Thuggee], we must seek the murderers at their homes, and drag them from their asylums.’

The Company’s principal failing hitherto – so Sleeman’s approvers assured him – had been its inability to maintain a constant pressure on the gangs themselves. Occasional arrests, rarely followed up, had never seriously

diminished

the efficiency of the great mass of Thugs, and had little effect on their

morale. The stranglers had long known, after all, that they were wanted men, and had grown used over the years to setbacks and even the occasional disaster. They took the resilience of their gangs for granted.

The key to the entire anti-Thug campaign thus lay in the ability of Sleeman and his record office to supply accurate and timely intelligence as to the likely movements of the principal jemadars and their gangs. Without the

information

supplied by the approvers and painstakingly processed and evaluated at Jubbulpore, the Company would never have acquired the ability to pursue the gangs to the very doorsteps of their own homes. And without that ability, the handful of sepoys and nujeebs at Sleeman’s disposal would have proved hopelessly inadequate to the task of hunting down the wanted men.

Perhaps the Superintendent’s most important breakthrough came during the first year of the anti-Thug campaign, when a solution was at last found to the problem of extracting consistently reliable information from the Company’s approvers. Thug informers had hitherto attempted to cooperate in shielding their own families and friends from arrest. Sleeman’s triumph was to set his most important prisoners against each other. The fresh round of denunciations that followed ended any prospect that the prisoners might continue to collude, and Sleeman was soon able to divide his approvers into three main groups according to their religion and caste. Feringeea and six other Brahmins formed one group; Kuleean Singh – the fearsome

low-caste

jemadar whose son had effected Feringeea’s capture – led another; the third was made up of five Muslim approvers. ‘The list,’ Sleeman

commented

with no small satisfaction when he reported to Smith, ‘may be relied upon, I believe. Feringeea is … animated by a deadly spirit of hatred against Kuleean Singh and Kara Khan, once the leader of the Musulman Thugs, in consequence of their having been instrumental in the conviction of Jurha and Rada Kishun, his nearest relations.

*

Kuleean Singh and Kara Khan are united in hatred against Feringeea and his class, but deadly opposed to each other.’ ‘Each party,’ the Superintendent added elsewhere, ‘has caused the arrest, capital punishment and transportation of many Thugs of every other party, and consequently they hate each other most cordially.’

An example of Sleeman’s detailed genealogies of the main Thug families, this one extending over eight generations. The name of the celebrated approver Feringeea can be seen towards the left.

The efficiency and the morale of the patrols despatched to hunt down the wanted Thugs was also high. Service with Sleeman was highly popular among the Company’s soldiers and nujeebs, who relished the opportunity to track down ‘the Thugs by whose hands so many of their comrades have

perished

’. The work itself was exciting, and men chosen for the service had good prospects of distinguishing themselves. Their biggest incentive, nonetheless, was money, for the rewards offered for the capture and

conviction

of leading Thugs were substantial, even when divided between the members of an entire patrol. The largest ever offered for a jemadar seems to have been the 1,000 rupees put on the head of Hurree, ‘the notorious Thug leader of Jhalone’. The men responsible for capturing Feringeea shared rewards amounting to 500 rupees, and 200 more were paid for ‘Zolfukar, son of Thugs, whose father has just been captured with eight men of his gang in the

jagir

of Poona’. During the six years in which the Company’s efforts against the Thugs were at their height, a total of more than 10,000 rupees was distributed among the thousand or so soldiers who took part in the campaign.

The nujeebs sent in search of Thugs were well equipped for their task. Each party travelled in the company of at least two approvers, each

representing

one of the four rival groups noted by Sleeman – who were weighted down with irons to prevent their escape. By consulting their informants, separately, the Company men were supposed to confirm the identities of the members of any gangs they met on the roads, and each was supplied with warrants giving them the power to arrest wanted Thugs wherever they were found. Most importantly of all, Sleeman’s troops received detailed intelligence from the record office at Jubbulpore informing them of the names, aliases and home villages of the Thug jemadars they were pursuing. Provided with definite objectives, the patrols usually achieved what was expected of them.

There were, hardly surprisingly, instances suggesting that parties of nujeebs were sometimes over-zealous. A few of these occasions – Sleeman himself contended – were relatively harmless; on one occasion a patrol

passing

through Gwalior discovered two known Thugs who had entered Sindhia’s service as

sepahees

, and went off to the nearest magistrate to secure an order for the men’s arrest. By the time they returned the Thugs, forewarned, had escaped, and when the patrol caught up with them at Bhurtpore a few days later, the suspects were detained while a warrant was secured. ‘In this,’

Sleeman added a little piously, ‘they exceeded their orders, and have been

punished

for it.’ But there were other instances that suggested some Company sepoys were corrupt. Sleeman was forced to forbid his patrols from hunting for Thug loot in the homes they searched; the lure of so much cash and goods proved too much for some. The leader of one patrol was found to have accepted bribes from a moonshee known to be an associate of Thugs. On another occasion, RT Lushington, the Company’s Resident at Bhurtpore, complained bitterly to Sleeman that a party of nujeebs had entered his rajah’s territory and arrested three suspected Thugs on the word of a prostitute and her pimp. One of the arrested men turned out to be a Brahmin and another was a member of the rajah’s palace guard; none of their names appeared on any of an embarrassed Sleeman’s lists of Thugs. ‘On this mere hearsay,’ Lushington protested in a letter sent directly to the Governor General, ‘respected members of the community are apprehended as murderers and are to be sent in chains to Saugor. I beg to ask whether it is consistent with justice to capture persons on such a charge and evidence, and this, too, without allowing the prisoners to say a word in their own defence?’

Despite occasional setbacks of this sort, the campaign progressed rapidly. Most Company officers, including most Residents, supported it. By the middle of 1832, Sleeman’s detachments had swept the roads in a circle through Baroda and Nagpore in the south, Bundelcund in the north-west and Jodhpore in the west. Gwalior and Rajpootana had been scoured and scores of alleged Thugs seized. Sleeman had also sent Major Stewart, the Company’s Resident at Hyderabad, a list of 150 Thugs believed to be at large in the Nizam’s domains with the request that he arrange for their arrest. Similar

letters

went out to the Residents at Indore and Delhi.

Particular attention was paid to the main routes into Hindustan frequented by sepoys travelling home on leave from Madras and Bombay in an effort to reduce the number of casualties inflicted on the Company’s troops each year by the Thug gangs. The Company’s nujeebs, Sleeman informed Smith,

are now provided with approvers well acquainted with the usual movements of all the principal Thugs who have hitherto considered the annual leave period as a legitimate kind of harvest, so we have a good chance of securing some of their gangs … Thugs have often told me that the reason why they choose the native officers and sepoys of our armies in preference to other

travellers is that they commonly carry more money and other valuable

articles

about them and are from their arms, their strength, self-confidence and haughty bearing more easily deceived by the vain humility and respect of the Thugs, and led off the high roads into jungly and solitary situations … where they are more easily murdered and their bodies disposed of.

By the end of 1832, the Company’s patrols were active over an area three or four times as big as Britain, and the Governor General, Bentinck, had agreed to nearly double the strength of the troops available to Sleeman. British efforts were by now being rewarded with substantial success. During the cold season of 1832–3 Sleeman calculated that only four jemadars remained at large in the whole of the central provinces, and the number of suspected Thugs being held in prison at Saugor had tripled to nearly more than 600. A vast quantity of loot had been recovered from the homes of

various

jemadars. One Thug leader’s home alone yielded 715 large pearls and 1,108 smaller ones, 65 large and 20 smaller diamonds, a large chest crammed with Spanish dollars and doubloons, numerous gold bangles, and hundreds of rings, bracelets, necklaces and earrings. On the few occasions when items of plunder could be identified by relations of the Thugs’ victims, the treasure was returned to its rightful owners. The rest – virtually all of the cash and goods recovered from Thug homes – was, with a nice irony, banked by Sleeman himself at Jubbulpore and used to pay the expenses of the sepoys and nujeebs hunting the men who had first plundered it.

The year ended on the most positive note yet struck in the regular reports sent by the Thuggy Department to FC Smith. ‘Three great results,’ Sleeman observed,

have already been produced by these extensive seizures. First, the roads have been secured from Thug depredations … Second, their confidence in each other has been so entirely destroyed that in the smallest parties seized there are some found ready to disclose the murders committed and to point out the bodies of the murdered … Thirdly, there is hardly a family of these wretches north of the Nerbudda of which we have not some of the members in prison, and thereby the means of learning what members are still at large, with increasing facilities of seizing them, and convicting them when seized.

The approvers had done their work. Sleeman had done his. Thuggee had been exposed, its most notable leaders hunted down and arrested, its methods and secrets laid bare – and, in some cases, exaggerated. The next step was to try the prisoners.