Thunder of the Gods (55 page)

The increasing employment of equestrians by the emperors – perhaps as a counterweight to the senate – resulted in the development of a hierarchy within the class, probably as a means of preventing clashes over perceived superiority. There were three orders of prestige, the

Viri Egregii

(Select Men),

Viri Perfectissimi

(Best Men) and the

Viri Eminentissimi

(Most Eminent of Men). We don’t know how these classes were organised or made distinct, but the assumption is that

Eminentissimi

was accorded only to the Praetorian Prefects (of which there were usually two at any one time),

Perfectissimi

to the major prefectures and offices of state, such as the governor of Egypt and the

Vigiles

, roles appointed by the emperor that effectively made these men his clients (in accordance with the long Roman tradition of patronage). The remainder of the equestrian class, it is assumed, were

Egregrii

.

Whatever the position, both senators and equestrians benefitted enormously from their service even before the obvious opportunities for corruption are taken into consideration. The prefect of an auxiliary cohort – the first step on the ladder of command – was paid 10,000 denarii, fifty times the basic pay accorded to his soldiers, and at the top end of the pay scale the governor of Egypt received 75,000 denarii a year. Even the lowest ranks of Rome’s social elite lived in a manner to which most of the empire’s population could barely have comprehended, never mind aspired.

By the late second century, the point at which the

Empire

series begins, the Imperial Roman Army had long since evolved into a stable organisation with a stable

modus operandi

. Thirty or so

legions

(there’s still some debate about the Ninth Legion’s fate), each with an official strength of 5,500 legionaries, formed the army’s 165,000-man heavy infantry backbone, while 360 or so

auxiliary cohorts

(each of them the equivalent of a 600-man infantry battalion) provided another 217,000 soldiers for the empire’s defence.

Positioned mainly in the empire’s border provinces, these forces performed two main tasks. Whilst ostensibly providing a strong means of defence against external attack, their role was just as much about maintaining Roman rule in the most challenging of the empire’s subject territories. It was no coincidence that the troublesome provinces of Britain and Dacia were deemed to require 60 and 44 auxiliary cohorts respectively, almost a quarter of the total available. It should be noted, however, that whilst their overall strategic task was the same, the terms under which the two halves of the army served were quite different.

The legions, the primary Roman military unit for conducting warfare at the operational or theatre level, had been in existence since early in the republic, hundreds of years before. They were composed mainly of close-order heavy infantry, well-drilled and highly motivated, recruited on a professional basis and, critically to an understanding of their place in Roman society, manned by soldiers who were Roman citizens. The jobless poor were thus provided with a route to both citizenship and a valuable trade, since service with the legions was as much about construction – fortresses, roads and even major defensive works such as Hadrian’s Wall – as destruction. Vitally for the maintenance of the empire’s borders, this attractiveness of service made a large standing field army a possibility, and allowed for both the control and defence of the conquered territories.

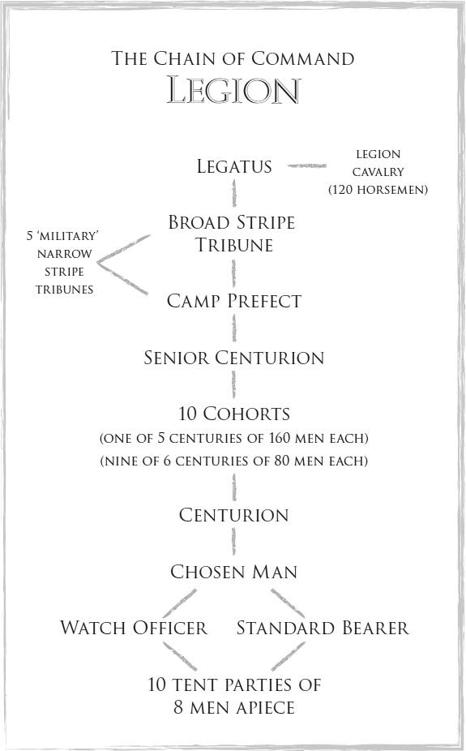

By this point in Britannia’s history three legions were positioned to control the restive peoples both beyond and behind the province’s borders. These were the 2nd, based in South Wales, the 20th, watching North Wales, and the 6th, positioned to the east of the Pennine range and ready to respond to any trouble on the northern frontier. Each of these legions was commanded by a

legatus

, an experienced man of senatorial rank deemed worthy of the responsibility and appointed by the emperor. The command structure beneath the legatus was a delicate balance, combining the requirement for training and advancing Rome’s young aristocrats for their future roles with the necessity for the legion to be led into battle by experienced and hardened officers.

Directly beneath the legatus were a half-dozen or so

military tribunes

, one of them a young man of the senatorial class called the

broad stripe tribune

after the broad senatorial stripe on his tunic. This relatively inexperienced man – it would have been his first official position – acted as the legion’s second-in-command, despite being a relatively tender age when compared with the men around him. The remainder of the military tribunes were

narrow stripes

, men of the equestrian class who usually already had some command experience under their belts from leading an auxiliary cohort. Intriguingly, since the more experienced narrow-stripe tribunes effectively reported to the broad stripe, such a reversal of the usual military conventions around fitness for command must have made for some interesting man-management situations. The legion’s third in command was the camp

prefect

, and older and more experienced soldier, usually a former centurion deemed worthy of one last role in the legion’s service before retirement, usually for one year. He would by necessity have been a steady hand, operating as the voice of experience in advising the legion’s senior officers as to the realities of warfare and the management of the legion’s soldiers.

Reporting into this command structure were ten

cohorts

of soldiers, each one composed of a number of eighty-man

centuries

. Each century was a collection of ten

tent parties

– eight men who literally shared a tent when out in the field. Nine of the cohorts had six centuries, and an establishment strength of 480 men, whilst the prestigious

first cohort

, commanded by the legion’s

senior cneturion

, was composed of five double-strength centuries and therefore fielded 800 soldiers when fully manned. This organisation provided the legion with its cutting edge: 5,000 or so well-trained heavy infantrymen operating in regiment and company-sized units, and led by battle-hardened officers, the legion’s centurions, men whose position was usually achieved by dint of their demonstrated leadership skills.

The rank of

centurion

was pretty much the peak of achievement for an ambitious soldier, commanding an eighty-man century and paid ten times as much as the men each officer commanded. Whilst the majority of centurions were promoted from the ranks, some were appointed from above as a result of patronage, or as a result of having completed their service in the

Praetorian Guard

, which had a shorter period of service than the legions. That these externally imposed centurions would have undergone their very own ‘sink or swim’ moment in dealing with their new colleagues is an unavoidable conclusion, for the role was one that by necessity led from the front, and as a result suffered disproportionate casualties. This makes it highly likely that any such appointee felt unlikely to make the grade in action would have received very short shrift from his brother officers.

A small but necessarily effective team reported to the centurion. The

optio

, literally ‘best’ or

chosen man

, was his second-in-command, and stood behind the century in action with a long brass-knobbed stick, literally pushing the soldiers into the fight should the need arise. This seems to have been a remarkably efficient way of managing a large body of men, given the centurion’s place alongside rather than behind his soldiers, and the optio would have been a cool head, paid twice the usual soldier’s wage and a candidate for promotion to centurion if he performed well. The century’s third-in-command was the

tesserarius

or

watch officer

, ostensibly charged with ensuring that sentries were posted and that everyone know the watch word for the day, but also likely to have been responsible for the profusion of tasks such as checking the soldiers’ weapons and equipment, ensuring the maintenance of discipline and so on, that have occupied the lives of junior non-commissioned officers throughout history in delivering a combat-effective unit to their officer. The last member of the centurion’s team was the century’s

signifer

, the

standard bearer

, who both provided a rallying point for the soldiers and helped the centurion by transmitting marching orders to them through movements of his standard. Interestingly, he also functioned as the century’s banker, dealing with the soldiers’ financial affairs. While a soldier caught in the horror of battle might have thought twice about defending his unit’s standard, he might well also have felt a stronger attachment to the man who managed his money for him!

At the shop-floor level were the eight soldiers of the tent party who shared a leather tent and messed together, their tent and cooking gear carried on a mule when the legion was on the march. Each tent party would inevitably have established its own pecking order based upon the time-honoured factors of strength, aggression, intelligence – and the rough humour required to survive in such a harsh world. The men that came to dominate their tent parties would have been the century’s unofficial backbone, candidates for promotion to watch officer. They would also have been vital to their tent mates’ cohesion under battlefield conditions, when the relatively thin leadership team could not always exert sufficient presence to inspire the individual soldier to stand and fight amid the horrific chaos of combat.

The other element of the legion was a small 120-man detachment of

cavalry

, used for scouting and the carrying of messages between units. The regular army depended on auxiliary

cavalry wings

, drawn from those parts of the empire where horsemanship was a way of life, for their mounted combat arm. Which leads us to consider the other side of the army’s two-tier system.

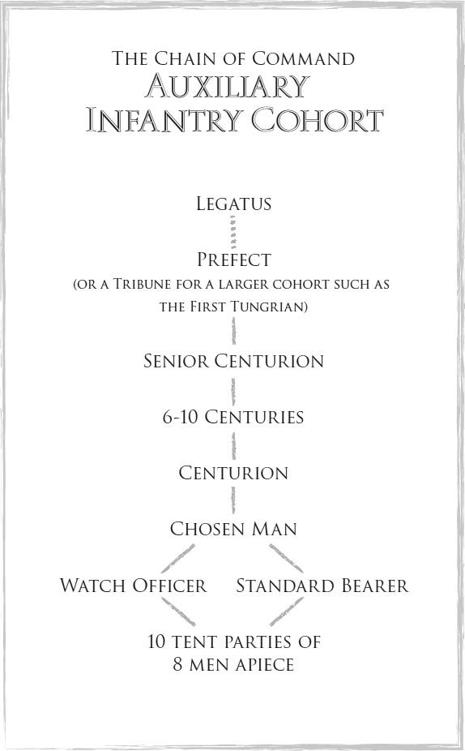

The

auxiliary cohorts

, unlike the legions alongside which they fought, were not Roman citizens, although the completion of a twenty-five-year term of service did grant both the soldier and his children citizenship. The original auxiliary cohorts had often served in their homelands, as a means of controlling the threat of large numbers of freshly conquered barbarian warriors, but this changed after the events of the first century AD. The Batavian revolt in particular – when the 5,000-strong Batavian cohorts rebelled and destroyed two Roman legions after suffering intolerable provocation during a recruiting campaign gone wrong – was the spur for the Flavian policy for these cohorts to be posted away from their home provinces. The last thing any Roman general wanted was to find his legions facing an army equipped and trained to fight in the same way. This is why the reader will find the auxiliary cohorts described in the

Empire

series, true to the historical record, representing a variety of other parts of the empire, including Tungria, which is now part of modern-day Belgium.

Auxiliary infantry was equipped and organised in so close a manner to the legions that the casual observer would have been hard put to spot the differences. Often their armour would be mail, rather than plate, sometimes weapons would have minor differences, but in most respects an auxiliary cohort would be the same proposition to an enemy as a legion cohort. Indeed there are hints from history that the auxiliaries may have presented a greater challenge on the battlefield. At the battle of Mons Graupius in Scotland, Tacitus records that four cohorts of Batavians and two of Tungrians were sent in ahead of the legions and managed to defeat the enemy without requiring any significant assistance. Auxiliary cohorts were also often used on the flanks of the battle line, where reliable and well drilled troops are essential to handle attempts to outflank the army. And while the legions contained soldiers who were as much tradesmen as fighting men, the auxiliary cohorts were primarily focused on their fighting skills. By the end of the second century there were significantly more auxiliary troops serving the empire than were available from the legions, and it is clear that Hadrian’s Wall would have been invalid as a concept without the mass of infantry and mixed infantry/cavalry cohorts that were stationed along its length.