Tiffany Girl (9 page)

Authors: Deeanne Gist

A

diminutive man paused at Reeve’s door, his hair flatly brushed, his face clean-shaven. “Excuse me, would you happen to know where Miss Jayne’s room is?”

“I’m afraid she’s not in.”

“Yes, I’m aware of that.”

Reeve hesitated. As a rule, gentleman callers waited in the parlor, even well-dressed ones twice her age.

The man pointed toward the foyer with his thumb. “I knocked and waited just inside the door, but no one ever came.”

Reeve sighed. “No, I don’t suppose they did. Was there something I could help you with?”

“I just wanted to see her room, is all, then I’ll be on my way. If you could tell me where it is, I’d be obliged.”

Placing his pen in its holder, Reeve chose his words carefully. “Did you have business with the lady?”

“I’m her father.”

“Are you?” Reeve stood and held out a hand. “Reeve Wilder.”

“Bert Jayne.” They shook. “I just wanted to make sure my girl was settled in all right.”

“She seems to be. Today was her first day of work.”

Looking down, Mr. Jayne ran a thumb over the rim of his hat. “I

never thought to hear words of that sort about any woman, but most especially not about my daughter.”

“I’m sorry.” And he was. He couldn’t imagine being the father of a working girl, even if she did work for a prestigious employer like Tiffany. Perhaps it was best not to mention the strikers who’d harassed his daughter.

“I’m sorry, too.” Jayne sighed. “Still, I wanted to see for myself that she was okay. If I’d waited until she was home, then it would look like I was condoning what she was doing—and I’m not. Not by a long shot. All the same, I’d like to see her room.”

Pushing in his chair, Reeve stepped into the hallway. “Her room’s right here next to mine.”

Jayne frowned. “So close? Isn’t there a woman’s floor?”

“Much to my sorrow, there is not. I’d give anything to have the women on their own floor, but Mrs. Klausmeyer lets out rooms on a first come, first served basis with no regard to gender.”

“Well, that’s certainly distressing news.” Jayne rubbed his forehead. “I do feel for you, though. Flossie’s definitely a jabber box, but I confess to missing the chatter. Home has become so quiet all of a sudden.”

Reeve could just imagine. Opening the door to her room, he stepped inside, then held it open for her father. A hodgepodge of rugs lay in a maze-like pattern on the floor, some circular, some rectangular. Every wall had furniture up against it with pictures, sketches, paintings, and china plates hanging above. One bed was shoved against the back wall like his, but unlike his it had a white quilt with intersecting rings made up of colorful fabrics. At its head, a matching pillow cover.

He’d never been in Miss Love’s room before. He wondered how much of this was hers and how much of it was Miss Jayne’s. He looked behind the door at the other bed. Her bed. It was up against the wall he shared with them—her voice always easier to hear than Miss Love’s. No simple quilt for Miss Jayne, though. Her

bed was covered with a fluffy white spread and a white lace pillow bordered with white lace ruffles. Above its brass headboard, a large painting of a woman at the seashore captured his full attention.

He moved closer, looking for the signature. And there it was. F. Jayne.

“It’s the best one she’s ever done,” her father said, standing just behind Reeve’s shoulder. “Far and away my favorite.”

Reeve tilted his head. It was actually quite good. The woman leaned against a railing, her red hair flowing in the breeze and changing color depending on where the sun hit it. The water was blue and sparkling, the sand white and begging to be walked upon. He could almost hear the waves, taste the salt, and feel the grit of the sand on his skin.

Standing there, beside the painting and the white linens on the bed, he felt as if he’d stepped into a summer day, full of light and sunshine and happiness. Sort of like her.

He took a quick step back and bumped into her father. “Excuse me.”

As much as Reeve wanted to return to his room, he didn’t feel right leaving. The man said he was Miss Jayne’s father, and he could see a little bit of resemblance around the mouth. Still, until he knew for certain, he’d stay put.

Mr. Jayne walked about the room, looking at the walls as if he were in a museum. Hands behind his back, he bent over and examined a sketch of a woman selling flowers to a well-dressed gentleman. A dress form holding a fashionable gown. A crowd of people boarding a steamer. A group of children playing hopscotch on the street. “Such a talent my girl has. Must have gotten it from her mother. I can’t draw to save my life.”

Reeve glanced at the sketches and paintings he referred to. Some weren’t bad, but he wasn’t sure he’d call Miss Jayne a talent. She was competent, as the seashore painting proved, but she was hardly the next Rembrandt.

Mr. Jayne stopped in front of a washstand. Instead of a wooden affair on spindly legs, the women had a full cabinet with an assortment of glass vials, china bowls, and porcelain vessels surrounding a fancy washbowl and ewer with floral designs and gold-leaf edges.

Mr. Jayne lifted a few of the lids and peeked at the various creams and liquids. “I’m a barber, you know.”

No, he didn’t know, but he didn’t say so.

“Taught her a thing or two about creams and such, and she caught on awfully fast. She’s a smart girl, my Flossie. She’d have made a great barber if she’d been a man.” He held a jar of liquid to his nose. “Smells just like her, don’t you think?” He held it out to Reeve.

Out of politeness, Reeve took a sniff. It smelled of roses. “I couldn’t really say, sir. I only see her at dinnertime, and the table we sit at is awfully large.”

Mr. Jayne screwed the lid back on and returned it to the washstand. “Well, of course you couldn’t say, but I could, and I can assure you, it smells just like her.” He took one last look about the room, then withdrew a card from his pocket. “Well, don’t tell her I was here. I want her to come home. If she knew I’d been here, she might take it as a sign of approval.”

Reeve accepted the card. So it was her father after all. “Mum’s the word, sir.”

Mr. Jayne clapped him on the shoulder. “That’s a good man. If we want to keep this women’s movement from gaining momentum, we’d best stick together. Good day, Wilder.”

“Good day.”

The man left as quickly and as quietly as he’d come. A shame his daughter wasn’t more like him.

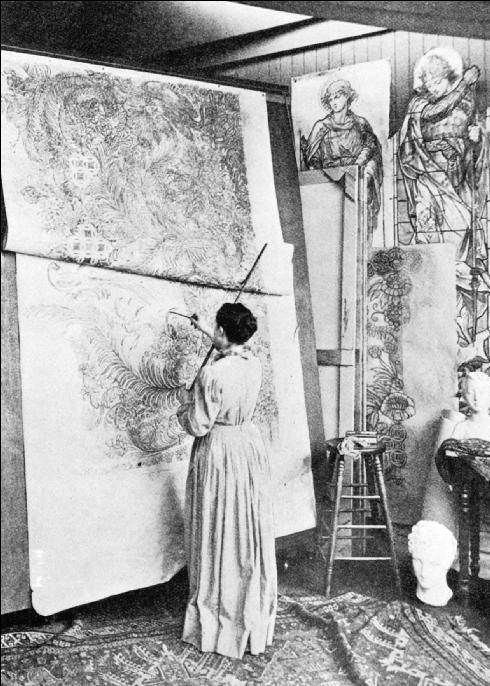

CARTOON

7

“She hadn’t been chosen to paint faces on the leaded glass windows, nor to paint watercolors onto the large hanging canvas, which she now knew they called a cartoon.”

CHAPTER

10

W

ith aching feet, Flossie squeezed onto the crowded streetcar that would take her home. Home to Klausmeyer’s Boardinghouse. Exhausted as she was, she couldn’t suppress the thrill of completing her first day of work. She hadn’t been chosen to paint faces on the leaded glass windows, nor to paint watercolors onto the large hanging canvas, which she now knew they called a cartoon. Instead, she’d been sent to the storeroom to restock colored glass.

Nan Upton, the Tiffany Girl she’d met out in the hall, had stood beside a cartoon going through trunks full of colored glass. She’d pick up a small sheet, hold it to the window, mutter something under her breath, then do the same thing with a different one. When she’d sorted through all the trunks and not found the color she was looking for, she’d started on barrels of colored glass. By the time she’d laid aside a selection weighing no more than a few pounds, well over a ton of glass had been strewn from one end of the storeroom to the other.

It had been Flossie’s job to put the pieces back, but rather than return them to any old trunk, she’d decided to sort them by color. All the greens in one trunk, the reds in another, and blues in yet another. No wonder Mr. Tiffany had lit up when he’d described

the characteristics of his opalescent glass to her. Never had she seen anything like it in her entire life.

Touching it, holding it up to the light, seeing how different textures created different results enthralled her, and slowed down her work considerably. When Mrs. Driscoll had come to find out what was taking her so long, she’d given Flossie a bit of a scolding.

“For heaven’s sake, look at all this glass. What on earth have you been doing?”

“Sorting it by color,” she’d answered. “It might take a bit of time up front, but I think it will save time in the end.”

“Nonsense. No one could ever sort Tiffany glass. It’s too variegated. How would you ever be able to decide? No, no. Just get it up off the floor and tables and into the trunks, then come along. There’s much to be done.”

With a great deal of disappointment, she’d done as she was told. It was hard to pout, though, when she’d been able to work with such a plethora of colors and designs.

The streetcar conductor gave a savage ring of the bell and tore around a corner, throwing Flossie into the men crammed up next to her in the overcrowded quarters. She hung on to a leather strap above her head. No one offered her a seat, no one offered her any space.

It was the same for all women on streetcars this time of day, whether they were students or working girls. This was the time reserved for men who rushed home to their wives who served up meals, fetched slippers, and birthed children. At least the glass strikers hadn’t been outside of Tiffany’s at the conclusion of the day, so she and the others had gone unmolested to the streetcar stop.

Still, the men on the five o’clock cars didn’t like them being there, and even though she knew better, it felt as if they’d all had some secret meeting and agreed to teach women students and

laborers a lesson: if you want to enter into a man’s world, then don’t expect to be treated differently.

But the women

were

treated differently. They were touched inappropriately under the guise of being helped on and off the car. They were groped by “bustle pinchers” taking advantage of crowded conditions, and they had things whispered to them the men would never dare to utter under normal circumstances.

She tightened her hold on the creaking strap. No matter how stiff she made herself, she couldn’t keep the men from brushing against her in an intimate fashion. All pretended it wasn’t happening, but all were very aware it was.

In an effort to distract herself, she tried to imagine what it would be like if she were to be the one selecting glass instead of restocking it. She’d realized at once it was the most critical step of the entire window-making process.

She definitely would have chosen a different piece for the Virgin Mary’s hair. The flow, density, and texture of the piece Nan had chosen was lovely—all of Mr. Tiffany’s glass was lovely—but Flossie had run across some others that were even better. She’d considered showing them to Nan, then recalled Nan had seen them and set them aside, which was why Flossie was having to restock them in the first place.

“West Fifty-Seventh!” the driver shouted, pulling the horses to a stop.

Excusing herself, Flossie pressed her way to the front and had almost made it to the door when her coat caught on something and her backside received a strong pinch. Squealing, she whirled around, grasping her coat and swatting the area behind her.