Time Travel: A History (19 page)

Read Time Travel: A History Online

Authors: James Gleick

Tags: #Literary Criticism, #Science Fiction & Fantasy, #Science, #History, #Time

With us acts are exempt from time, and we

Can crowd eternity into an hour,

Or stretch an hour into eternity.

That’s Lucifer, per Lord Byron, on good authority. Luke 4:5: “And the devil, taking him up into an high mountain, showed unto him all the kingdoms of the world in a moment of time.”

Kurt Vonnegut must have remembered this when he created his Tralfamadorians, adorable green aliens who experience reality in four dimensions: “All moments, past, present and future, always have existed, always will exist. The Tralfamadorians can look at all the different moments just that way we can look at a stretch of the Rocky Mountains, for instance.” Eternity is not for us. We may aspire to it, we may imagine it, but we cannot have it.

If we’re going to speak literally, nothing is

outside of time.

Asimov ends his story by nullifying it. Who has the privilege of changing history? Not the Technicians, only the author. On the last page the entire previous narrative—the people we have met, the stories we have watched unfold—is erased with the stroke of a pen. The rewriters of history are written out.

*1

“Harlan had seen many women in his passages through Time, but in Time they were only objects to him, like walls and balls, barrows and harrows, kittens and mittens.”

*2

The

OED

cites Asimov as the coiner of several words, including

robotics,

but

endochronic

is not one of them. It has not yet caught on.

*3

Silly? Yet in the distant future—2015—Panasonic marketed a camera that it said recorded images “one second prior to and one second after pressing the shutter button.”

*4

This passage appeared in the first published version of

The End of Eternity

and disappeared from the book version.

NINE

Buried Time

So in the future, the sister of the past, I may see myself as I sit here now but by reflection from that which then I shall be.

—James Joyce (1922)

IN ITS ISSUE

of November 1936,

Scientific American

transported readers into the future:

The time is A.D. 8113. The air channels of the radio-newspaper and world television broadcasting systems have been cleared for an important announcement…a story of international importance and significance.

(Evidently it seemed plausible that the world’s communications channels could be “cleared” on command.)

The television sight-and-sound receivers in every home throughout the world carry the thread of the story. In the Appalachian Mountains near the eastern coast of the North American continent is a crypt that has been sealed since the year A.D. 1936. Carefully its contents have been guarded since that date, and today is the day of the opening. Prominent men from all over the world assemble at the site to witness the breaking of the seal that will disclose to the waiting world the civilization of an ancient and almost forgotten people.

The ancient and almost forgotten people of 1936 America, that is. This puff was headlined “Today—Tomorrow” and written by Thornwell Jacobs, a former minister and advertising man, now president of Oglethorpe University, a Presbyterian college in Atlanta, Georgia. Oglethorpe had been shuttered since the Civil War. Jacobs re-created it in partnership with a suburban land developer. Now he was promoting his idea, “heartily endorsed” by

Scientific American,

for a Crypt of Civilization, to be waterproofed and sealed in the basement of the administration building on his campus. Jacobs was also a teacher: his course in cosmic history was mandatory for Oglethorpe seniors. Not presuming that Oglethorpe University itself would last forever, he proposed that the crypt should be “deeded in trust to the Federal government, its heirs, assigns, and successors.” Its contents? A thorough record of the era’s “science and civilization.” Certain books, especially encyclopedias, and newspapers preserved in a vacuum or inert gas or on microfilm (“preserved in miniature on motion picture film”). Everyday items such as foods and “even our chewing gum.” Miniature models of automobiles. And: “There should also be included a complete model of the capitol of the United States, which, within a half-dozen centuries, will probably have disappeared completely.”

Time

magazine and

Reader’s Digest

picked up the story, and Walter Winchell touted it in one of his radio broadcasts, and the crypt was completed at a ceremony in May 1940. Something about “burying” appealed to people. David Sarnoff of the Radio Corporation of America declared, “The world is now engaged in burying our civilization forever and here in this crypt we leave it to you.” The United Press reported:

ATLANTA, Ga., May 25—They buried the twentieth century here today.

Mickey Mouse and a bottle of beer, an encyclopedia and a movie-fan magazine were put to rest along with thousands of other objects depicting life as it is known today.

Buried our civilization? Buried the twentieth century? The century kept going, making new stuff, even after 1940. What Jacobs really buried was a collection of knickknacks. There was a set of Lincoln Logs children’s toys, a sheet of aluminum foil, some women’s stockings, model trains, an electric toaster, and phonograph records bearing the voices of Franklin Roosevelt, Adolf Hitler, King Edward VIII, and other world leaders. Some items bound to cause puzzlement: “1 distributor head cover”; “1 sample of catlinite”; “1 lady’s breast form.” All neatly shelved, a stainless-steel door was welded shut, and so it remains, a quiet room in the basement of what is now called Phoebe Hearst Memorial Hall.

*1

Imagine how excited the world will be when May 28, 8113, finally arrives.

*2

—

MEANWHILE,

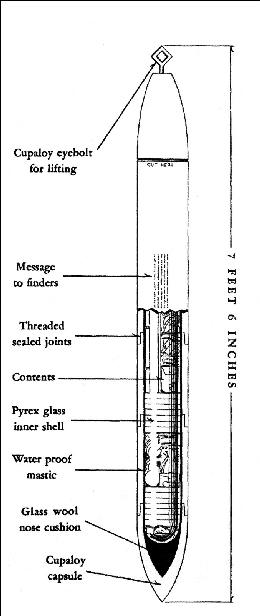

the event in Georgia was upstaged by another up north. A public relations man at the Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Corporation named G. Edward Pendray—a rocket enthusiast and sometime science-fiction writer—trumped the crypt with a swifter and sleeker package for the future, to be plunged into the ground at the 1939 New York World’s Fair—the “World of Tomorrow”—in Flushing, Queens. Instead of a whole room, Westinghouse designed a shiny half-ton torpedo, seven feet long, with an inner glass tube and an outer shell of Cupaloy, a special new alloy of rust-proof hardened copper. Pendray first wanted to call this device a “time bomb,” but that term had a different meaning.

So on second thought he came up with “time capsule.” Time, encapsulated. Time in a capsule. A capsule for all time.

The newspapers waxed enthusiastic. “The famous ‘time capsule,’ ” the

New York Times

called it, days after it was announced in the summer of 1938. “Its contents will no doubt prove to be distinctly quaint to the scientists of 6939 A.D.

*3

—as strange, probably, as the furnishings of Tut-ankh-Amen’s tomb seemed to us.” The Tutankhamun reference was apt. The burial chamber of the Eighteenth Dynasty pharaoh had been discovered in 1922, causing a sensation: the royal sarcophagus was intact; the British excavators uncovered precious turquoise, alabaster, lapis lazuli, and preserved flowers that disintegrated upon touch. Inner rooms revealed statuettes, chariots, model boats, and wine jars. The pharaoh’s funerary mask, solid gold and striped with blue glass, became iconic. So did the very idea of a buried past.

Archeology helped people think about the future as well as the past. Cuneiform tablets were turning up in the desert sands, bearing secrets. The Rosetta Stone, another icon, sat at the British Museum, where for decades no one could read its message—a message to the future, people said, but it hadn’t been meant that way. It was for immediate distribution: a decree from king to subjects; pardons and tax rebates. Remember, the ancients had no futurity. They cared less for us than we do for the people of 8113, apparently. Egyptians preserved their treasures and remains for passage to the afterlife, but they weren’t waiting for

the future.

They had a different place in mind. Whatever their intent, their eventual legatees were archeologists. So when 1930s Americans began interring their own treasures, they quite self-consciously considered themselves to be enacting archeology in reverse. “We are the first generation equipped to perform our archeological duty to the future,” said Thornwell Jacobs.

At the World’s Fair, Westinghouse saved space by enclosing 10 million words on microfilm. (They included instructions on how to make a microfilm reader. The time capsule did not have room for one, so a small microscope had to do.) “

THE ENVELOPE FOR A MESSAGE TO THE FUTURE BEGINS ITS EPIC JOURNEY

,” said the official Westinghouse

Book of Record of the Time Capsule of Cupaloy,

*4

which was printed and distributed to libraries and monasteries for preservation. Written in an odd faux-biblical prose—as if addressing monks of the Middle Ages, rather than historians of the future—the book advertised the achievements of modern technology:

Over wires pour cataracts of invisible electric power, tamed and harnessed to light our homes, cook our food, cool and clean our air, operate the machines of our homes & factories, lighten the burdens of our daily labor, reach out and capture the voices and music of the air, & work a major part of all the complex magic of our day.

We have made metals our slaves, and learned to change their characteristics to our needs. We speak to one another along a network of wires and radiations that enmesh the globe, and hear one another thousands of miles away as clearly as though the distance were only a few feet….

All these things, and the secrets of them, and something about the men of genius of our time and earlier days who helped bring them about, will be found in the Time Capsule.

By way of artifacts, the capsule could carry only a few carefully selected items, including a slide rule, a dollar’s worth of U.S. coins, and a pack of Camel cigarettes. And one piece of headwear:

Believing, as have the people of each age, that our women are the most beautiful, most intelligent, and best groomed of all the ages, we have enclosed in the Time Capsule specimens of modern cosmetics, and one of the singular clothing creations of our time, a woman’s hat.

There was also movie footage—or, as the

Book of Record

helpfully explained, “pictures that move and speak, imprisoned on ribbons of cellulose coated with silver.”

Several dignitaries were invited to write directly to the people of the future—whoever, whatever, they might be. The dignitaries were grumpy. Thomas Mann informed his distant descendants, “We know now that the idea of the future as a ‘better world’ was a fallacy of the doctrine of progress.” In his message, Albert Einstein chose to characterize twentieth-century humanity this way: “People living in different countries kill each other at irregular time intervals, so that also for this reason anyone who thinks about the future must live in fear and terror.” He added hopefully, “I trust that posterity will read these statements with a feeling of proud and justified superiority.”

This first time capsule so-called was not the first time anyone thought to hide away some memorabilia, of course. People, like squirrels, are natural hoarders, collectors, and buriers. In the late nineteenth century, amid the rising consciousness of the future, “centennial” fairs inspired time-capsule-like impulses. In 1876 Anna Diehm, a wealthy New York publisher and Civil War widow, set out leather-bound albums for thousands of visitors to sign at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition and then locked them in an iron safe, along with a gold pen used for the signing and photographs of herself and others, and inscribed a message to posterity: “It is the wish of Mrs. Diehm that this safe may remain closed until July 4, 1976, then to be opened by the Chief Magistrate of the United States.”

*5

But the Westinghouse time capsule and the Oglethorpe crypt were the first self-conscious attempts at wholesale cultural preservation for the sake of a notional future—reverse archeology. They mark the beginning of what scholars have called the “golden age” of time capsules: the era when people, worldwide and in increasing numbers, have buried in the earth thousands of parcels, ostensibly intended for the information and education of future creatures unknown. In his study

Time Capsules: A Cultural History,

William E. Jarvis calls them “time-information transfer experiences.” They represent a special version of time travel. They also represent a special kind of foolishness.