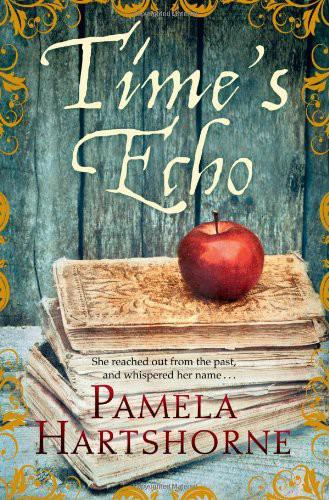

Time's Echo

For my parents, with love,

and for the people of York, past and present.

I feel no fear, not yet. I am just astounded to find myself in the air, looking down at the murky rush of the river. It is as if time itself has paused, and I am somehow

suspended between the sky and the water, between the past and the present, between then and now. Between disbelief and horror.

It is All Hallows’ Eve, and I am going to die.

Part of me knows that quite well. But another part refuses to comprehend that it is really happening. Refuses to believe that this is not a dream, that I won’t wake up. That this morning

was the last time I would ever feel the floorboards cool and smooth beneath my feet, the last time I would hear the creak of the stairs or the rain pattering on the roof.

The last time I would smooth my daughter’s hair under her cap.

‘I won’t be long,’ I promised her.

In the distance, a bell is striking. The city is going about its business, the way it always does. The market on Pavement is open. The stallholders will be poking at their sagging awnings to get

rid of the rain that has pooled in the morning downpour. They will be grumbling at the mud and the lost business when everyone was huddled indoors.

I should be there. I have things to do. We need fish, we need salt. Bess is growing fast. I want to buy her some new shoes. I will go this afternoon.

Except that I won’t. I will die instead.

It seems odd that it should be the thought of something as ordinary as shoes that bumps time onwards, out of that strange moment when everything stopped, but so it is. It is

now

after

all, and suddenly everything is happening too fast. I plunge into the water and it closes, brown and bitter, over my face. I can feel it rushing into my petticoat, filling my sleeves, dragging me

down with the weight of the cloth.

And I remember him, bending over me, whispering that he is going to take Bess now, he will raise her as his own, and no one will say him nay.

‘I will do what I like with her, Hawise,’ he said.

Now

I am afraid, remembering that.

Now

I struggle, as horror clogs my mind, but my thumb is tied to my toe and I can’t swim, even if I knew how. My skirts are too heavy, the water is too cold, and when I open my

mouth to scream, to curse him again, the river gushes in through the stocking tied around my face to keep me quiet. It is cold and rank and thick in my throat. It is too late. The river is fast and

furious, sweeping me away like a barrel, down towards the sea I have never seen, and never will. I am jetsam, tossed overboard to save the city.

I sink and rise, then sink deeper, and the more I choke, the more water invades me. There is a terrible pain in my ears, behind my eyes, and my lungs are on fire.

I am flailing, thrashing in the water, but I sink deeper and deeper. I don’t know which way is up and which is down any more. There is nothing but panic and pain and the water blocking my

throat, and the bright, terrifying image of Bess looking up at him trustingly, taking his hand.

I need to go back. I need to do things differently, so that I can keep my daughter safe.

‘

Bess

,’ I try to say, as if I could reach her, as if she could hear me, as if she could understand my fear and my anguish.

But I can’t speak and I can’t breathe, I can’t

breathe

. My lungs are full of water, my throat is clamped shut. The pressure behind my eyes is agonizing, and there is a

screaming in my ears, but how can I be screaming when I can’t draw a breath? Sweet Jesù, I have to have air – I have to, or I will die – but I don’t know where the

surface is and I fail desperately, uselessly, against the terror as the river, uncaring, sucks me down, down, down and away into the dazzling dark.

I lurched awake on a desperate, rasping gasp. My eyes snapped open and I stared into the darkness, gripped by anguish for a daughter I had never had, while fear clicked

frantically in my throat and my pulse roared with the memory. I could feel the weight of the strange dress I had been wearing, and the stiffness of the linen cap binding my hair. The foul taste of

the river was so vivid still that I gagged.

I’m used to drowning. I’ve drowned so many times in my dreams that you would think my subconscious would learn to stop fighting the terror and the choking and the screaming of my

lungs and the pain, the

pain

of it. You’d think that at some level it would know that eventually I will pop up out of sleep, the way I popped up in the middle of the sea, where the

wave spat me out of its maw at last; but it never does.

My usual nightmares are so tangled up with memories of the tsunami that it’s hard sometimes to distinguish one from the other, but that night in York the dream was different. That night,

there were no palm trees stirring languidly above my head, the way there usually were in my nightmare. I wasn’t standing on the hot sand, and Lucas wasn’t digging on the beach, his thin

little back bent over his spade. There was no decision: to turn back or go on. No mistake. That night, the sea didn’t rush out of nowhere and gobble me up.

Instead, I dreamt of a river, brown and sullen. I dreamt of wearing heavy skirts instead of a sarong over my bikini. I dreamt of a daughter, not a little Swedish boy I barely knew.

Only the drowning was the same.

Slowly, slowly, the agonizing pain in my lungs eased and I could breathe properly. As my heart stopped jerking, my eyes adjusted to the darkness and I blinked, puzzled by the strange light and

the muffled quality of the night.

I strained my ears for the slow slap of the overhead fan, the mournful cry of the satay-seller pushing his cart along the

gang

, even the rasp of insects in the tropical night, but

instead all I heard was the swish of tyres on wet tarmac and the faint clunk of a car changing gear.

That odd, orange light through the curtains was from a street lamp. I struggled towards full consciousness. I wasn’t drowning in a cold river. I was in my dead godmother’s bed in

York.

It was the smell I’d noticed first. Sweet, putrid, faintly disquieting. I wrinkled my nose as I pushed the door open into a pile of accumulated junk mail and unpaid

bills. Grunting, I lugged in my suitcase and swung my backpack off my shoulder and onto the tiled floor, before shoving the door shut with my foot. The click of the Yale lock was loud in the

silence.

The house was dark, the air thick and unfriendly, but that was only to be expected. It had been closed up since Lucy’s death, more than a month earlier. I felt around for a switch and

stood, blinking in the sudden light, taking stock of my surroundings. I was in a narrow hallway with two doors on the left. Straight ahead was a steep staircase rising into shadows. It was a small,

unpretentious Victorian terraced house, and the only thing that surprised me about that first evening was how very ordinary it was. Lucy had always prided herself on being unconventional.

‘

Bess

.’

The voice sounded so close that I jumped. ‘Hello?’ I said uncertainly.

Silence.

‘Hello?’ I said again, feeling a bit silly. ‘Is there anybody there?’

But of course there wasn’t anybody there. The house had been locked up. On either side people were watching television, curtains drawn against the wet April night. All I’d heard was

someone talking in the street outside.

Embarrassed by the way my heart was thudding, I switched on the overhead light in the front room. This was more like the Lucy I remembered, I thought. The walls were painted a stifling red and

decorated with strange, symbolic pictures. A dream-catcher hung in the window, and everywhere there were crystals and dusty bowls of herbs.

I wandered over to the fireplace and poked through the jumble of candles and figurines on the mantelpiece. There, lurking amongst all the knick-knacks, I identified the source of the smell that

had been nagging at me: a rotting apple. It was brown and puckered with mould, and something in me jerked at the sight of it.

‘

Bess

.’

The name rippled in the air, like a breath against my cheek, and I looked up, startled, to catch a glimpse of myself in the dusty mirror above the mantelpiece. For a moment it was as if another

woman was looking back at me, a stranger with dark hair and pale-grey eyes like mine, but such an expression of horror on her face that I gasped and recoiled.

But it was only me. A pulse was hammering in my throat, and I put a hand up to still it.

God, I looked awful, I realized. It wasn’t surprising I hadn’t recognized myself for a moment. I’d spent the past thirty-six hours on the move, from check-in desk to departure

gate, from baggage carousels to station platforms, shuffling along in endless queues and through interminable security checks. Trapped in planes and trains and artificial lighting, my body clock

was so confused that I’d lost track of time completely.

I stuck out my tongue at my reflection and turned away.

The second door led to a parlour, similarly decorated in oppressive reds and purples, and beyond it a galley kitchen, where I found another apple on the worktop. No wonder the house smelt of

rotting fruit. Lucy must have had a thing about apples, I decided. This one was yellowish-brown with sagging skin. Repelled, I threw it in the bin and let the lid clang shut.

I was buzzing with exhaustion, but too wired to sleep. I put the kettle on and decided to take my bags upstairs while it boiled, but when I picked up my backpack and put a foot on the bottom

step, I found myself hesitating. It did look dark up there.

‘Don’t go,’ Mel had said when I rang her. ‘York’ll be boring and cold. Come to Mexico, Grace. I can get you a job at the school. You’d love it here,’

she said. ‘Think jugs of margaritas.’ She lowered her voice enticingly. ‘Think hot beaches and hot chilli and hot Mexican men. What more could you want?’

I laughed. ‘Nothing,’ I said. ‘I’d love to come. I just need to sort out my godmother’s stuff first.’

‘Get the solicitor to do it all,’ Mel advised. ‘You should be out here having a good time, not poking around in an old person’s house.’

‘Lucy wasn’t that old,’ I protested, ‘and the solicitor did say he’d arrange everything for me.’

‘Well, then.’

‘It’s just . . . I feel I owe it to Lucy to do it myself,’ I tried to explain. ‘It’s a question of trust.’

I’d been shocked when John Burnand rang me in Jakarta to tell me that my godmother had died. ‘Preliminary enquiries suggest that she drowned,’ he said.