Tipping the Velvet (66 page)

Read Tipping the Velvet Online

Authors: Sarah Waters

Would that make her love me, more than Lilian?

âYou can send me the money, too,' I said to Kitty at last; and I told her my address, and she nodded, and said she'd remember.

We gazed at one another then. Her lips were damp and slightly parted; and she had paled, so that her freckles showed. Involuntarily I thought back to that night at the Canterbury Palace, when I had met her first and learned I loved her, and she had kissed my hand, and called me âMermaid', and thought of me as she should not have. Perhaps the same memory had occurred to her, for now she said, âIs this how it's to end up, then? Won't you let me see you again; you might come and visit -'

I shook my head. âLook at me,' I said. âLook at my hair. What would your neighbours say, if I came visiting you? You'd be too afraid to walk upon the street with me, in case some feller called out!'

She blushed, and her lashes fluttered. âYou have changed,' she said again; and I answered, simply: âYes, Kitty, I have.'

She raised her hands to lower her veil. âGood-bye,' she said.

I nodded. She turned away; and as I stood and watched her, I found that I was aching slightly, as from a thousand fading bruises ...

I cannot let you go,

I thought,

so easily as that!

While she was still quite near I took a step into the sunshine, and looked about me. Upon the grass beside the tent there was a kind of wreath or bower â part of some display that had come loose and been discarded. There were roses on it: I bent and plucked one, and called to a boy who was standing idly by, handed the flower to him and gave him a penny, and told him what I wanted. Then I moved back into the shadows of the tent, behind the wall of sloping canvas, and watched. The boy ran up to Kitty; I saw her turn at his cry, then stoop to hear his message. He held the rose to her, and pointed back to where I stood, concealed. She turned her face towards me, then took the flower; he raced off at once to spend his coin, but she stood quite still, the rose held before her in her clasped, gloved fingers, her veiled head weaving a little as she tried to pick me out. I don't believe she saw me, but she must have guessed that I was watching, for after a minute she gave a kind of nod in my direction - the slightest, saddest, ghostliest of footlight bows. Then she turned; and soon I lost her to the crowd.

I thought,

so easily as that!

While she was still quite near I took a step into the sunshine, and looked about me. Upon the grass beside the tent there was a kind of wreath or bower â part of some display that had come loose and been discarded. There were roses on it: I bent and plucked one, and called to a boy who was standing idly by, handed the flower to him and gave him a penny, and told him what I wanted. Then I moved back into the shadows of the tent, behind the wall of sloping canvas, and watched. The boy ran up to Kitty; I saw her turn at his cry, then stoop to hear his message. He held the rose to her, and pointed back to where I stood, concealed. She turned her face towards me, then took the flower; he raced off at once to spend his coin, but she stood quite still, the rose held before her in her clasped, gloved fingers, her veiled head weaving a little as she tried to pick me out. I don't believe she saw me, but she must have guessed that I was watching, for after a minute she gave a kind of nod in my direction - the slightest, saddest, ghostliest of footlight bows. Then she turned; and soon I lost her to the crowd.

Â

I turned then, too, and headed back into the tent. I saw Zena first, making her way out into the sunshine, and then Ralph and Mrs Costello, walking very slowly side by side. I didn't stop to speak to them; I only smiled, and stepped purposefully towards the row of chairs in which I had left Florence.

But when I reached it, Florence was not there. And when I looked around, I could not see her anywhere.

âAnnie,' I called - for she and Miss Raymond had drifted over to join the group of toms beside the platform - âAnnie, where's Flo?'

Annie gazed about the tent, then shrugged. âShe was here a minute ago,' she said. âI didn't see her leave.' There was only one exit from the tent; she must have passed me while I was gazing after Kitty, too preoccupied to notice her ...

I felt my heart give a lurch: it seemed to me suddenly that if I didn't find Florence at once, I would lose her for ever. I ran from the tent into the field, and gazed wildly about me. I recognised Mrs Macey in the crowd, and stepped up to her. Had she seen Florence? She had not. I saw Mrs Fryer again: had she seen Florence? She thought perhaps she had spotted her a moment before, heading off, with the little boy, towards Bethnal Green ...

I didn't stop to thank her, but hurried away - shouldering my way through the crush of people, stumbling and cursing and sweating with panic and haste. I passed the

Shafts

stall again - did not turn my head, this time, to see whether Diana was still at it, with her new boy - but only walked steadily onwards, searching for a glimpse of Florence's jacket or glittering hair, or Cyril's sash.

Shafts

stall again - did not turn my head, this time, to see whether Diana was still at it, with her new boy - but only walked steadily onwards, searching for a glimpse of Florence's jacket or glittering hair, or Cyril's sash.

At last I left the thickest crowd behind, and found myself in the western half of the park, near the boating-lake. Here, heedless of the speeches and the debates that were taking place within the tents and around the stalls, boys and girls sat in boats, or swam, shrieking and splashing and larking about. Here, too, there were a number of benches; and on one of them - I almost cried out to see it! - sat Florence, with Cyril a little way before her, dipping his hands and the frill of his skirt into the water of the lake. I stood for a moment to get my breath back, to pull off my hat and wipe at my damp brow and temples; then I walked slowly over.

Cyril saw me first, and waved and shouted. At his cry Florence looked up and met my gaze, and gave a gulp. She had taken the daisy from her lapel, and was turning it between her fingers. I sat beside her, and placed my arm along the back of the bench so that my hand just brushed her shoulder.

âI thought,' I said breathlessly, âthat I had lost you ...'

She gazed at Cyril. âI watched you talking with Kitty.'

âYes.'

âYou said - you said she would never come back.' She looked desperately sad.

âI'm sorry, Flo. I'm so sorry! I know it ain't fair, that she did, and Lilian will never ...'

She turned her head. âShe really came to - ask you back to her?'

I nodded. Then, âWould you care,' I asked quietly, âif I went?'

âIf you went?' She swallowed. âI thought you'd gone already. I saw a look upon your face ...'

âAnd did you care?' I said again. She gazed at the flower between her fingers.

âI made up my mind to leave the park and go home. There seemed nothing to stay for - not even Eleanor Marx! Then I got as far as here and thought, “What would I do at home, with you not there ... ?”' She gave the daisy another twist, and two or three of its petals fell and clung to the wool of her skirt. I looked once about the field, then turned to face her again, and began to speak to her, low and earnestly, as if I were arguing for my life.

âFlo,' I said, âyou were right, what you said before, about that address I gave with Ralph. It wasn't mine, I didn't mean the words - at least, not then, when I said them.' I came to a halt, then put a hand to my head. âOh! I feel like I've been repeating other people's speeches all my life. Now, when I want to make a speech of my own, I find I hardly know how.'

âIf you are fretting over how to tell me you are leaving -'

âI am fretting,' I said, âover how to tell you that I love you; over how to say that you are all the world to me; that you and Ralph and Cyril are my family, that I could never leave - even though I was so careless with my own kin.' My voice grew thick; she gazed at me but didn't answer, so I stumbled on. âKitty broke my heart - I used to think she'd killed it! I used to think that only she could mend it; and so, for five years I've been wishing she'd come back. For five years I have scarcely let myself think of her, for fear that the thought would drive me mad with grief. Now she has turned up, saying all the things I dreamed she'd say; and I find my heart is mended already, by you. She made me know it.

That

was the look you saw on my face.' I raised a hand to stop a tickling at my cheek, and found tears there. âOh, Flo!' I said then. âOnly say - only say you'll let me love you, and be with you; that you'll let me be your sweetheart, and your comrade. I know I'm not Lily -'

That

was the look you saw on my face.' I raised a hand to stop a tickling at my cheek, and found tears there. âOh, Flo!' I said then. âOnly say - only say you'll let me love you, and be with you; that you'll let me be your sweetheart, and your comrade. I know I'm not Lily -'

âNo, you're not Lily,' she said. âI thought I knew what that meant - but I never did, till I saw you gazing at Kitty and thought I should lose you. I've been missing Lily for so long, it's come to seem that wanting anything must be only another way of wanting her; but oh! how different wanting seemed, when I knew it was you I wanted, only you, only you ...'

I shifted closer towards her: the paper in my pocket gave a rustle, and I remembered romantic Miss Skinner, and all the friendless girls who Zena had said were mad in love with Flo, at Freemantle House. I opened my mouth to tell her; then thought I wouldn't, just yet - in case she hadn't noticed. Instead, I gazed again about the park, at the crush of gay-faced people, at the tents and stalls, the ribbons and flags and banners : it seemed to me then that it was Florence's passion, and hers alone, that had set the whole park fluttering. I turned back to her, took her hand in mind, crushed the daisy between our fingers and - careless of whether anybody watched or not - I leaned and kissed her.

Cyril still squatted with his frills in the lake. The afternoon sun cast long shadows over the bruised and trampled grass. From the speakers' tent there came a muffled cheer, and a rising ripple of applause.

Sarah Waters

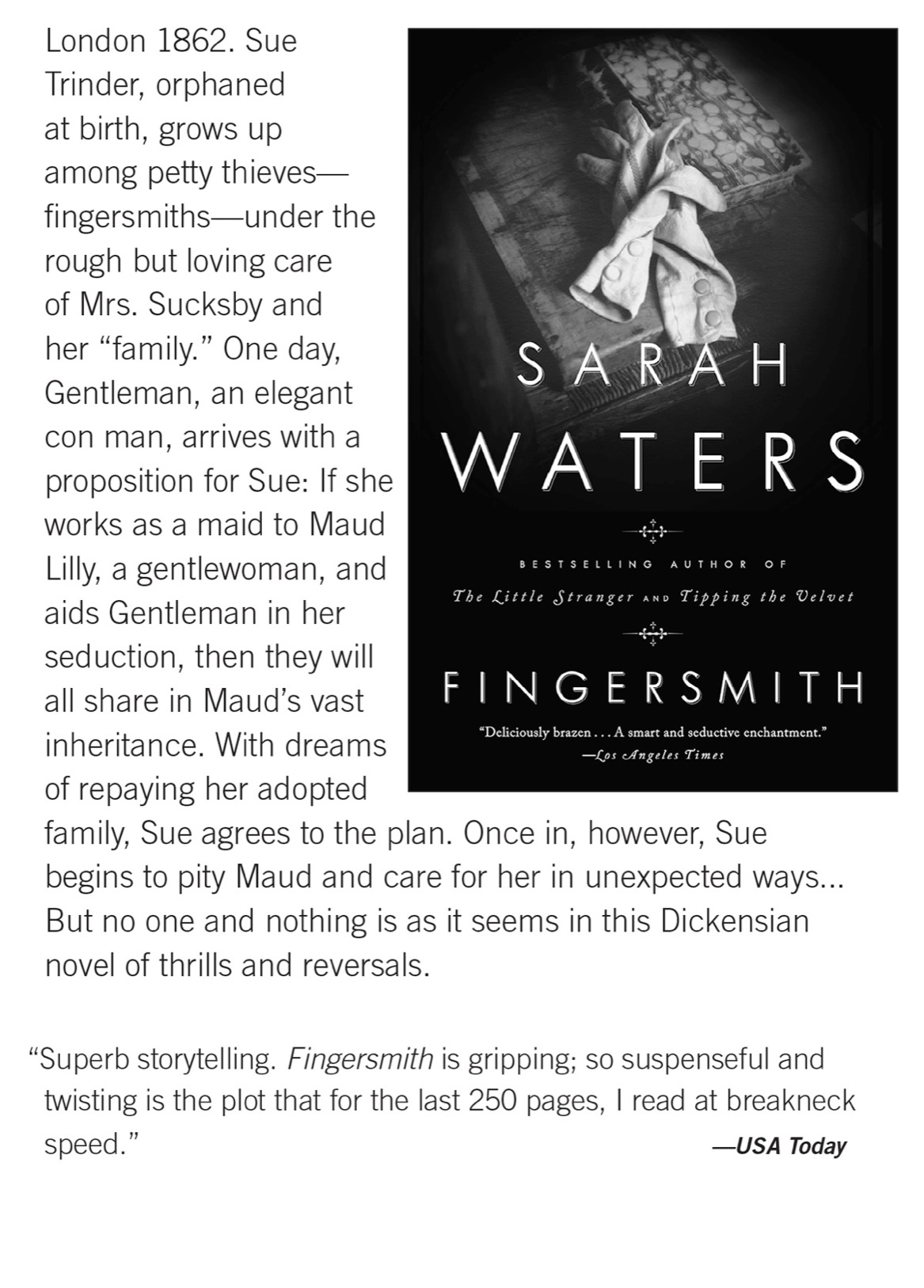

was born in Wales in 1966 and now lives in London. She is the author of the novels

Tipping the Velvet, a New York Times

Notable Book,

Affinity,

and

Fingersmith. Affinity,

her second novel, won the Somerset Maugham Award, an American Library Association Award, and a Ferro-Grumley Award. Waters was also named the

Sunday Times

Young Writer of the Year in 2000.

was born in Wales in 1966 and now lives in London. She is the author of the novels

Tipping the Velvet, a New York Times

Notable Book,

Affinity,

and

Fingersmith. Affinity,

her second novel, won the Somerset Maugham Award, an American Library Association Award, and a Ferro-Grumley Award. Waters was also named the

Sunday Times

Young Writer of the Year in 2000.

Other books

Shipbuilder by Dotterer, Marlene

Murder Most Maine by Karen MacInerney

The Vow by Lindsay Chase

Reno Gabrini: A Family Affair by Mallory Monroe

Come Unto These Yellow Sands by Josh Lanyon

Arresting God in Kathmandu by Samrat Upadhyay

Memory: Book Two (Scars 2) by West, Sinden

El complot de la media luna by Clive Cussler, Dirk Cussler