Titanic (3 page)

Authors: Deborah Hopkinson

The

Titanic

was almost ready — and a good thing too, since there was less than a week to go. The ship reached Southampton a little after midnight on Friday, April 4. Final preparations began early Friday morning. The ship was loaded with 4,427 tons of coal, adding to the 1,880 tons already on board.

The next day, Saturday, more than three hundred crew members were signed up — bakers, firemen, stewards, window cleaners, butchers, and stewardesses — everything the floating palace needed. Fewer than fifty of the crew were trained seamen, experienced with such things as lowering lifeboats or handling small boats at sea; most were hotel staff, stokers (to keep the furnaces loaded with coal), or engineers.

On Monday, trains brought food supplies to G Deck, where they were loaded into storerooms and refrigerators. Although the full list of supplies for the

Titanic

has been lost, we know that her sister ship, the

Olympic

, took on massive quantities of food for a transatlantic voyage. It’s likely that the

Titanic

set sail with supplies that included 75,000 pounds of meat; 11,000 pounds of fish; 10,000 pounds of sugar; 36,000 oranges; 7,000 heads of lettuce; 40 tons of potatoes; 40,000 eggs; and 20,000 bottles of beer.

In addition to the supplies for passengers, the

Titanic

was carrying a wide assortment of items. The cargo list included cartons of books; 100 bales of shelled walnuts; 1,196 bags of potatoes; 15 cases of rabbit hair; 63 cases of champagne; plus cheese; brandy; wine; orchids; lace; surgical instruments; feathers for hats; gloves; preserves; mussels; tea; and silk. One passenger was even shipping a red Renault automobile!

Twenty-four-year-old Violet Jessop signed on as a stewardess in the days before sailing. The eldest of six children, Violet had once dreamed of getting an education, but when her mother fell ill, Violet had to help support the family. She followed her mother’s path and became a stewardess. Violet was a hard worker and took a lot of pride in caring for “her” passengers, turning down beds at night, bringing tea trays to passengers, and, of course, helping anyone who got seasick.

The layout of the

Titanic

was familiar to Violet, since she had worked on the

Olympic

. The two ships were indeed quite similar, one reason why many of the photographs we see today of the

Titanic

’s interiors are actually of the

Olympic

. However, there were a few differences. One obvious one was that the forward part of the promenade on A Deck on the

Titanic

was enclosed, rather than open. The

Titani

c also had its new restaurant, the Café Parisien, which offered fantastic views of the sea for diners.

(Preceding image)

The first class Café Parisien on B Deck.

There were also other, smaller changes. According to Violet, Thomas Andrews, the

Titanic

’s designer, had asked the

Olympic

’s crew for suggestions to improve the new ship and make their long hours at work easier. Violet and her fellow crew members had been eager to contribute ideas for improvements in the stewards’ quarters, called “glory holes.” On most ships, as Violet knew from her own experience, stewards lived in cramped quarters with little comfort or privacy. The glory hole, Violet wrote, was usually “a foul place, often . . . infected with bugs . . .”

The stewards and stewardesses were delighted with their clean new accommodations on the

Titanic.

Violet found that her bunk was placed the way she had suggested to give her more privacy, and she also had a separate, small wardrobe so that she did not have to share a closet with her roommate. (And since her roommate smoked cigarettes, Violet was pleased that now her own clothes wouldn’t smell like smoke!) The crew was so happy they invited Thomas “Tommy” Andrews to visit the glory hole to thank him in person. “His gentle face lit up with real pleasure,” Violet remembered fondly.

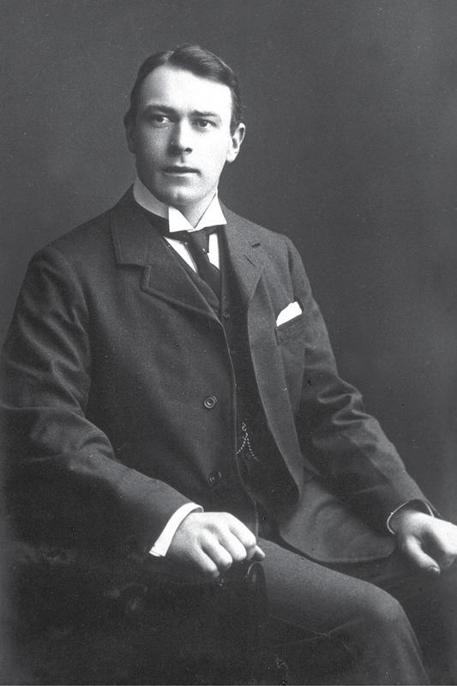

(Preceding image)

Thomas Andrews was the shipbuilder in charge of the design and plans for the

Titanic

.

Thomas Andrews was thirty-nine years old. He had begun working as an apprentice at Harland and Wolff shipbuilders, where his uncle was part owner, when he was only sixteen. Andrews was bright, well liked, dedicated, and hardworking. He probably knew more about the ship than anyone and would be traveling on the

Titanic

’s maiden voyage to take notes and make adjustments. In those last hectic days before sailing, Violet saw his tall frame everywhere. “Often during our rounds we came upon our beloved designer going about unobtrusively with a tired face but a satisfied air.”

Thomas Andrews wasn’t satisfied unless everything was right. He didn’t just walk around giving orders: He rolled up his sleeves and got to work. He even put into place “racks, tables, chairs, berth ladders, and electric fans . . . ” his secretary recalled.

“He was always busy, taking the owners around the ship, interviewing engineers, officials, managers, agents, subcontractors . . . and superintending generally the work of completion.”

How proud he must have been! For Thomas Andrews, this magnificent ship was the culmination of years of hard work and planning. His last letter to his wife, written on the eve of the maiden voyage, is full of pride and the sense of accomplishment he must have felt. “The

Titanic

is now about complete and will, I think, do the old Firm credit tomorrow when we sail.”

Stewardess Violet Jessop was ready too. “Life aboard started off smoothly. Even Jenny, the ship’s cat and part of the crew, had immediately picked herself a comfortable corner; she varied her usual Christmas routine on previous ships by presenting

Titanic

with a litter of kittens in April.”

But fireman Joe Mulholland, who had worked on the

Titanic

from Belfast to Southampton, said later that he decided not to sign on for the maiden voyage across the Atlantic when he saw Jenny carry her tiny kittens off, one by one, down the gangplank.

He thought it was a bad omen.

Even an experienced British seaman like thirty-eight-year-old Second Officer Charles Herbert Lightoller (sometimes known by the nickname “Lights”), who’d worked on White Star ships for twelve years, was impressed by the massive size of the

Titanic

.

“I was thoroughly familiar with pretty well every type of ship afloat, from a battleship and a barge, but it took me fourteen days before I could with confidence find my way from one part of that ship to another by the shortest route,” he said.

Getting a new ship ready to sail — especially one that would cater to so many rich and prominent people — took a tremendous amount of effort and attention to small details. Lightoller and the other officers needed to make sure everything was in working order for the voyage. “With the

Titanic

it was night and day work, organizing here, receiving stores there . . .”

But they shared Thomas Andrews’s sense of excitement. Everyone could see that the

Titanic

was something special. Lightoller put it this way: “It was clear to everybody on board that we had a ship that was going to create the greatest stir British shipping circles had ever known.”

Sailing day arrived at last. It now seemed to Lightoller that the

Titanic

was like a nest of bees about to swarm. Finally, just after noon on Wednesday, April 10, the gangways were lowered, the whistle blew, and the

Titanic

was off!

As the ship got under way, an eager Frank Browne stood ready, anxious to capture this moment with his camera. He leaned as far over the railing as he dared. “With a feeling akin to suppressed excitement I watched the scene, for it was my first experience of actual travel on an ocean liner, and for a beginning I could not have ‘struck’ a bigger boat . . .”

The

Titanic

glided out of her berth. Suddenly Frank heard a crack: The wash of the giant ship had caused the ropes holding the ocean liner

New York,

moored nearby, to break. Cut loose, the smaller boat began to drift — right into the

Titanic

’s path.

“A voice beside me said, ‘Now for a crash,’ and I snapped my shutter,” Frank said.

Captain E. J. Smith and the harbor pilot acted quickly to avoid a collision by ordering the engines full astern to keep the great ship from moving forward and break a sort of suction between the ships. Tugs then managed to put lines on the

New York

to pull her away. In the end it took nearly an hour more to get the

Titanic

safely out of the harbor. Before long, though, she was crossing the English Channel to pick up more passengers in Cherbourg, France.

The passengers sat down to enjoy their first meal on board.