To Die For (32 page)

Authors: Joyce Maynard

Wherever we went after that, it was always “How’s Suzanne doing?” “Poor Suzanne.” “Is there anything we can do?” “She’s been so brave.”

After the boys were arrested, my parents still kept it up. Talking about how unfair it was, the hatchet job the media was doing and so forth. And of course, if anyone had thought to stick a microphone under my nose I would’ve come out with the same lines. Only nobody did.

But since you’ve asked, I’ll tell you what. She was my baby sister, and it’s true, I worshiped her. You know what they say— when in Rome …

She was irresistible. Look at me, when I was four years old she moved in and wrecked my life, and still I adored her. She had this ability to manipulate a person. Like one of those commercials you see, where you know they’re handing you a line, you know they’re working on you, and still you can’t help it. When the commercial’s over, you’ve just got to get up and pour yourself a Coke, or put Dove with Moisturizer on your shopping list. Listen, I’m a beautician. I know hair-care products. And still, when I’m finished watching Cybill Shepherd tell me why she uses L’Oreal, I’m ready to run right out and buy myself a bottle. Suzanne had that kind of power over a person. My dad couldn’t resist it. Larry Maretto couldn’t. You think a sixteen-year-old boy could say no to a person like that?

I’ll tell you a story. When I was ten—Suzanne was six—my grandmother sent me this locket that used to be her mother’s. Me being the oldest girl and all. That was one thing Suzanne could never take away.

This was a wonderful locket. It opened up so you could put a picture inside. And on the outside, etched into the gold, it had the word

Daughter

in very flowery script, with a little circle of diamond chips around the edges. First thing I did when I got the locket was get a really little picture of my mother to put inside. And I never took that locket off.

It drove Suzanne crazy. I mean, just about every special treat we’d get, there’d always be two of them. A brunette Madame Alexander Cissy doll for me, a blonde for Suzanne. A blue organdy dress for me, pink for Suzanne. We had matching Easter hats, matching Schwinn Traveller bikes with streamers, matching Princess phones for our rooms, not that I had much use for mine.

But with this locket, there was just no way to even things up. Not that my father didn’t try. Even though it was my birthday present, he told her, when he saw how upset she was, that he’d buy her a new locket, and have the word

Daughter

engraved on that one too. When she said that wouldn’t be the same he bought her a charm bracelet with all these sterling silver charms of all her favorite things: a ballet slipper, a miniature telephone, a sportscar, even a miniature TV set with dials that actually turned. She still wasn’t happy.

She said why didn’t I trade her the charm bracelet for the locket. And it was a neat charm bracelet. But it was also something you could go out and buy at a store, which was different from a locket your grandmother gave you, handed down to the oldest daughter in the family for three generations. And anyway, the charms fit with her life, not mine. So I said no.

Two, three months after I got the locket, we took a trip to Cape Cod, and I left it home in case it got lost in the waves. When we got home, I searched everywhere, but I couldn’t find it. I turned my room upside down looking for that locket, and for years after, I kept hoping it would show up, but it never did. Finally I just gave up. I even forgot about it.

You know something? After Suzanne died, my mother asked me to clean out the condo. It would just be too painful for her, you know? So I was cleaning out her drawers. And what do I find, tucked under a whole stack of Victoria’s Secret bras and panties, but my grandmother’s locket. I opened it up. But instead of the picture of my mother that I’d put inside, it was a picture of Suzanne.

Funny how things work out, isn’t it? Me being the only child again. Sunday nights now I always try to have dinner with my parents, who have been nearly destroyed by all of this business. So there it is, just the three of us again. I’m not the big sister anymore. Just the daughter. And incidentally, I’ve lost eighteen pounds. Stress, you could say. The funny thing is, I’m not even dieting, and still the weight keeps falling off. What do you know?

T

HAT’S IT.

Y

OU WANT

to know what I got to look forward to? A hundred years looking at these four walls, if I live that long.

I never thought I was going to get elected President or nothing. But I didn’t figure I’d end up like this neither. My dick might as well get petrified and drop off, for all I need it now.

The other night, I can’t say which on account of they start to blend together, I’m laying there and I decide to count the times we done it. Starting with that time at the beach. Ending with a night at her condo. That was the last time.

You know what? It added up to fourteen. Fourteen times, total. Maybe two hours of fucking, max. And the part that kills me is, I can’t hardly remember anymore what was so great about it. I know it must’ve been. I used to say I’d die for it. But I can’t even remember what it felt like anymore.

T

HE OUTLINE OF THE

story told here was suggested to me by a recent, highly publicized murder. I used, in a novelistic way, those facts made known to me through television and newspaper reports. But when those facts contradicted my imaginative and fictional necessities, I chose to pursue my own imagination.

The story I really wanted to tell is not about a specific set of characters and circumstances. I wanted in some way to explore questions of fidelity, love, sexual obsession, ambition, violence, and how our thoughts about these things are created and manipulated by television, movies, popular music and magazines. The question that interested me most was: Where do our motivations come from for self-fulfillment, for sexual attraction, for compassion and, finally, for love? I imagine all writers share these kinds of concerns.

So this is not a book about a specific murder case, or any individuals connected with such a case. It would be unfair to align the characters in this novel with those beings who gave me some inspiration. A frequently quoted line from Flaubert comes to mind: “Madame Bovary, c’est moi.” Madame Bovary, that’s me. To some terrible extent, all the characters in this and every other novel I’m ever likely to write represent elements of my own self. Names, places, characteristics, personal histories, ultimate guilt, ultimate responsibility, are all my own invention.

I

N THAT LONELY PERIOD

when a person is consumed with the writing of a book, no individual is more valuable than one who can read what the writer has produced and offer guidance. A handful of such good and trusted friends read or listened to portions of this manuscript and offered thoughts and criticism that helped immeasurably. I particularly want to thank Ernest Hebert, Bill Barton, Vicky Schippers, Audrey LaFehr, Graf Mouen, Susan Herman, Lynn Pleshette, Bob Carvin, and Bill Oster.

Joyce Maynard is the bestselling author of eleven books of fiction and nonfiction. She is best known for her memoir

At Home in the World

and her novel

Labor Day

, both bestsellers. Since launching her writing career as a teenager, Maynard has been a commentator on CBS radio, a contributor to National Public Radio’s “All Things Considered,” and a reporter for the

New York Times

, as well as a speaker on parenthood, family, and writing. She has published hundreds of essays and columns for publications such as

Vogue

;

More

;

O, The Oprah Magazine

; and the

New York Times

; in addition to many essay collections.

Born in Durham, New Hampshire, in 1953, Maynard began publishing her stories, essays, and poems when she was fourteen years old. She won numerous awards for her work before entering college at Yale University in 1971. During her freshman year, Maynard sent examples of her work to the

New York Times

, prompting an assignment: She was to write an article for them about growing up in the sixties. In April 1972 that article, “An Eighteen-Year-Old Looks Back on Life,” graced the cover of the magazine, earning her widespread acclaim and instant fame.

Maynard’s story also caught the eye of reclusive author J. D. Salinger, then fifty-three years old, who wrote her a letter praising her work—launching a correspondence that ultimately led Maynard to drop out of college and move to New Hampshire to live with the author. Their relationship lasted ten months.

Maynard never returned to college. In 1973 she published her first memoir,

Looking Back

, a follow-up to her

New York Times Magazine

article published the year before. Having lived alone in New Hampshire in her early twenties, in 1976 she was offered a job as a reporter for the

New York Times

and moved to New York City. She left the newspaper in 1977 when she married Steve Bethel and returned to New Hampshire. The couple went on to have three children: Audrey, Charlie, and Wilson.

Maynard’s first novel,

Baby Love

, published in 1981, earned the praise of several renowned fiction writers including Anne Tyler, Joseph Heller, and Raymond Carver. Her next book,

Domestic Affairs

(1987)—a collection of her syndicated columns, which had run in newspapers across the country—reflected on her experiences as a wife and mother and further cemented Maynard’s status as one of the best-loved modern American memoirists.

In 1986, an area in Maynard’s home state of New Hampshire was selected by the US Department of Energy as a finalist to become the first-in-the-nation high-level nuclear waste dump. Maynard was one of the organizers of the resistance to that project, and she wrote a cover story about it that was published in April of that year and was widely believed to have contributed to the government’s decision to suspend the nuclear waste dump plan.

Maynard’s marriage ended in 1989—an experience she wrote about in her “Domestic Affairs” columns. Many major newspapers discontinued the column abruptly at this point, citing Maynard’s impending divorce as indication that she was no longer equipped to write about family life. Maynard continued writing—though for a much smaller audience—in the

Domestic Affairs Newsletter

.

In keeping with her practice of communicating actively with her readers, Maynard established a website in 1996; she was one of the first writers to do so, and she was a regular and visible presence through the brand-new technology of her site’s discussion forum.

Forbidden by Salinger to speak of him, Maynard chose to remain silent about their relationship for twenty-five years, until her daughter turned eighteen. Her decision to write about the experience in her 1998 memoir

At Home in the World

resulted in an avalanche of criticism, but eventually led to further disclosures by other women who had been in his life. Salinger died in 2010.

Maynard has also written two children’s books and two young-adult novels; of these,

The Usual Rules

was named by the American Library Association as one of the ten best young-adult novels of 2003. Her literary fiction includes

To Die For

(1991),

Where Love Goes

(1994),

Labor Day

(2009), and

The Good Daughters

(2010).

To Die For

was adapted into a film of the same name starring Nicole Kidman.

Labor Day

is currently being adapted for the screen by director Jason Reitman, and is set to star Kate Winslet and Josh Brolin.

The mother of three grown children, Maynard now lives in Northern California where, in addition to continuing her career as a writer and speaker, she performs regularly as a storyteller with the Moth and Porchlight. She also runs the annual Lake Atitlán Writing Workshop in a small Mayan village on the shores of Lake Atitlán, Guatemala.

Maynard in 1955.

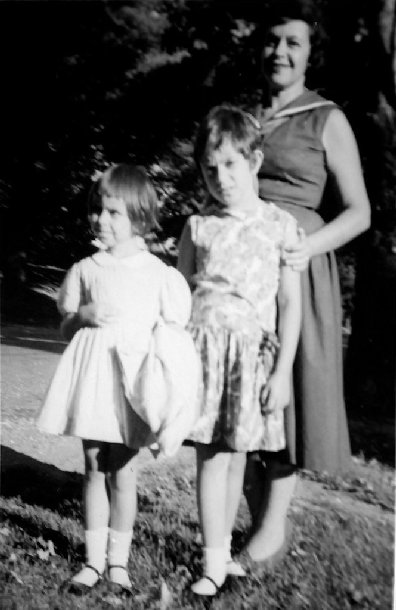

Maynard and her sister Rona with their mother in Durham, New Hampshire.