To Paradise

Authors: Hanya Yanagihara

A Little Life

The People in the Trees

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2022 by Hanya Yanagihara

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Doubleday, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

doubleday

and the portrayal of an anchor with a dolphin are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Cover painting:

Iokepa, Hawaiian Fisher Boy,

oil on canvas, by Hubert Vos, 1898. History and Art Collection / Alamy Stock Photo

Cover design by Na Kim

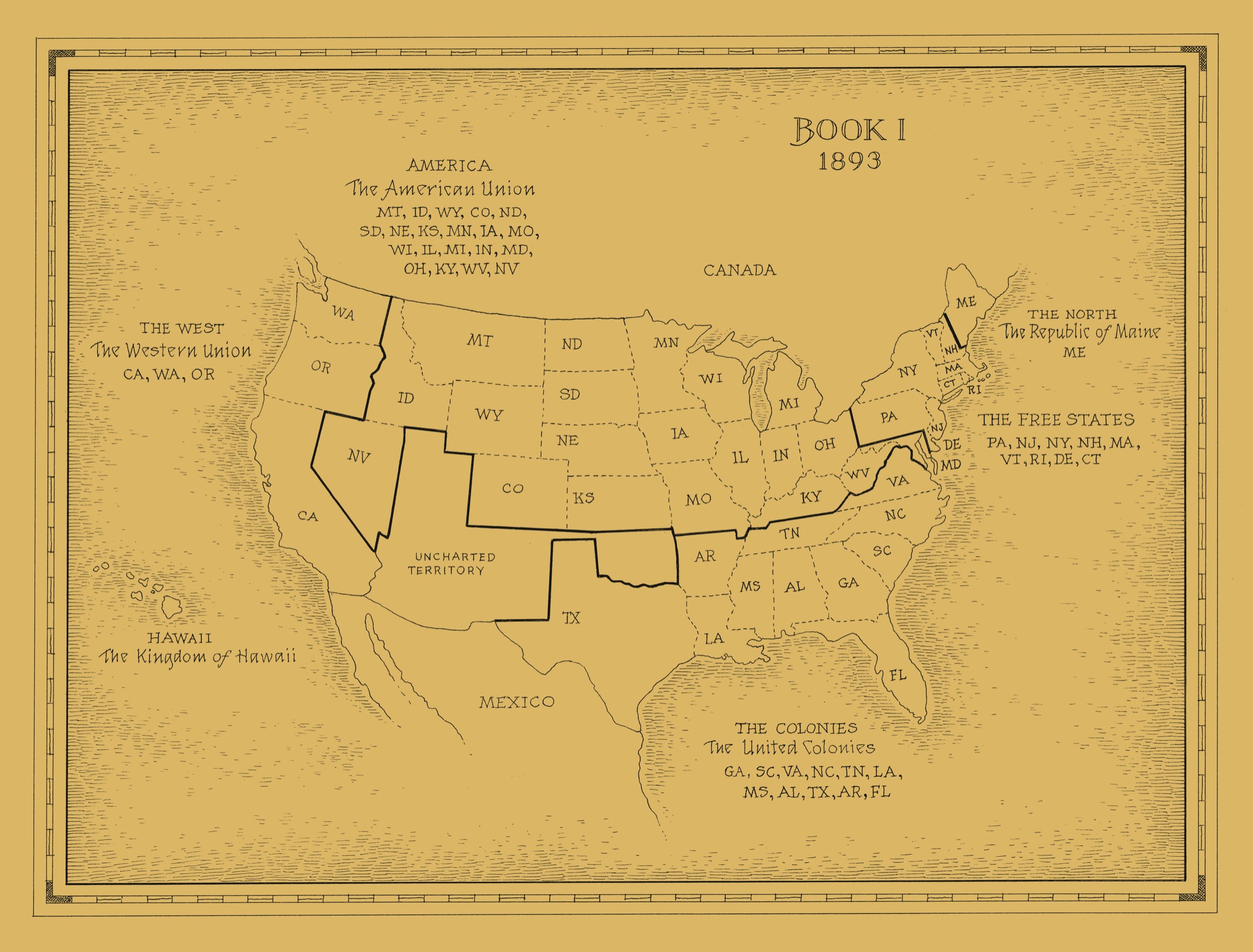

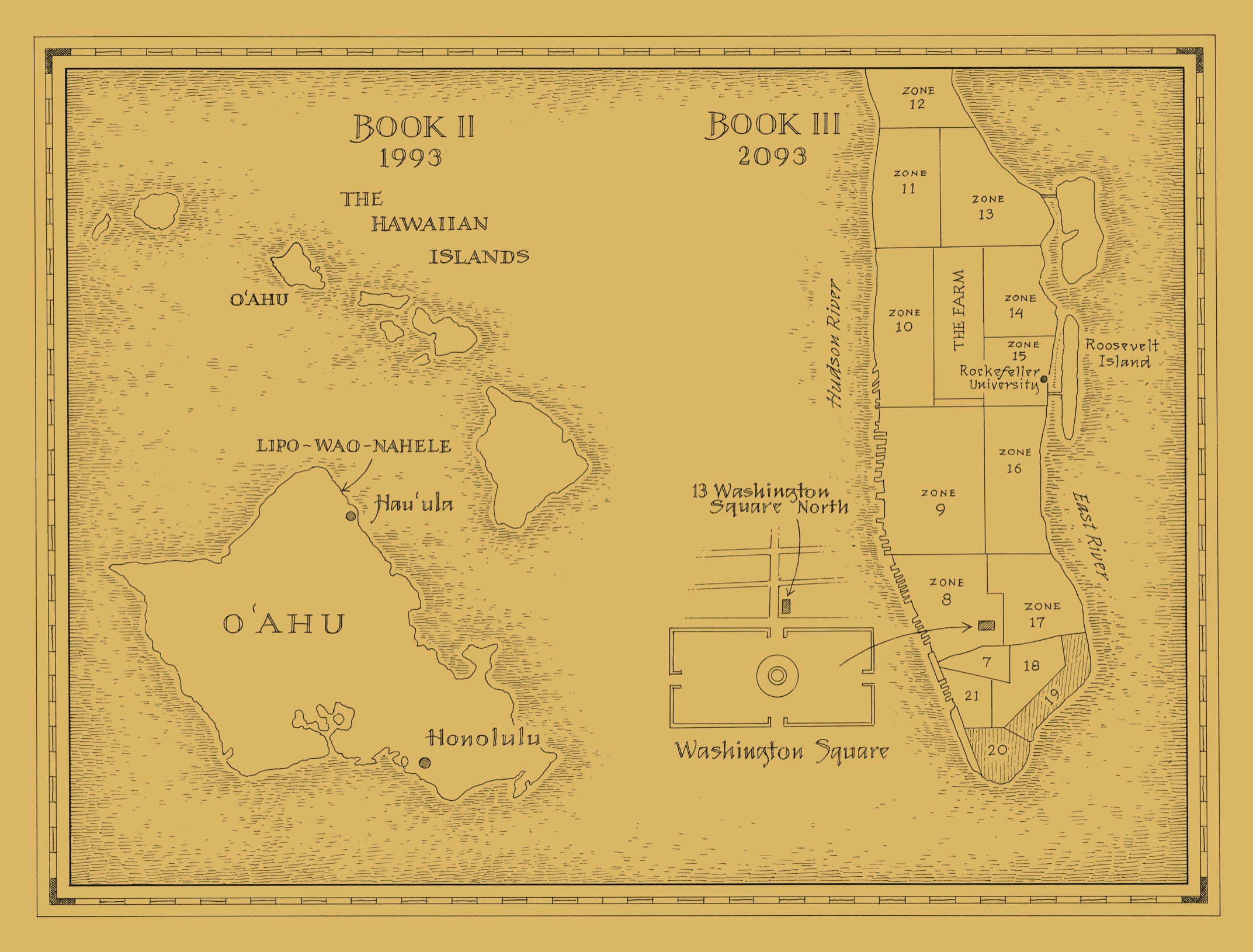

Maps by John Burgoyne

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021943460

isbn

9780385547932 (hardcover)

isbn

9780385547949 (ebook)

isbn

9780385548410 (open market)

ep_prh_6.0_138917749_c0_r0

To Daniel Roseberry

who saw me through

and

To Jared Hohlt

always

SQUARE

He had come into the habit, before dinner, of taking a walk around the park: ten laps, as slow as he pleased on some evenings, briskly on others, and then back up the stairs of the house and to his room to wash his hands and straighten his tie before descending again to the table. Today, though, as he was leaving, the little maid handing him his gloves said, “Mister Bingham says to remind you that your brother and sister are coming tonight for supper,” and he said, “Yes, thank you, Jane, for reminding me,” as if he’d in fact forgotten, and she made a little curtsy and closed the door behind him.

He would have to go more quickly than he would were his time his own, but he found himself being deliberately contrary, walking instead at his slower pace, listening to the clicks of his boot heels on the pavestones ringing purposefully in the cold air. The day was over, almost, and the sky was the particular rich ink-purple that he couldn’t see without remembering, achily, being away at school and watching everything shade itself black and the outline of the trees dissolve in front of him.

Winter would be upon them soon, and he had worn only his light coat, but nevertheless, he kept going, crossing his arms snug against his chest and turning up his lapels. Even after the bells rang five, he put his head down and continued moving forward, and it wasn’t until he had finished his fifth circumnavigation that he turned, sighing, to walk north on one of the paths to the house, and up its neat stone steps, with the door opening for him before he reached the top, the butler reaching already for his hat.

“In the parlor, Mister David.”

“Thank you, Adams.”

Outside the parlor doors he stood, passing his hands repeatedly over his hair—a nervous habit of his, much as the repeated smoothing of his forelock as he read or drew, or the light drawing of his forefinger beneath his nose as he thought or waited for his turn at the chessboard, or any number of other displays to which he was given—before sighing again and opening both doors at once in a gesture of confidence and conviction that he of course did not possess. They looked over at him as a group, but passively, neither pleased nor dismayed to see him. He was a chair, a clock, a scarf draped over the back of the settee, something the eye had registered so many times that it now glided over it, its presence so familiar that it had already been drawn and pasted into the scene before the curtain rose.

“Late again,” said John, before he’d had a chance to say anything, but his voice was mild and he seemed not to be in a scolding mood, though one never quite knew with John.

“John,” he said, ignoring his brother’s comment but shaking his hand and the hand of his husband, Peter; “Eden”—kissing first his sister and then her wife, Eliza, on their right cheeks—“where’s Grandfather?”

“Cellar.”

“Ah.”

They all stood there for a moment in silence, and for a second David felt the old embarrassment he often sensed for the three of them, the Bingham siblings, that they should have nothing to say to one another—or, rather, that they should not know how to say anything—were it not for the presence of their grandfather, as if the only thing that made them real to one another were not the fact of their blood or history, but him.

“Busy day?” asked John, and he looked over at him, quickly, but John’s head was bent over his pipe, and David couldn’t tell how he had intended the question. When he was in doubt, he could usually interpret John’s true meaning by looking at Peter’s face—Peter spoke less but was more expressive, and David often thought that

the two of them operated as a single communicative unit, Peter illuminating with his eyes and jaw what John said, or John articulating those frowns and grimaces and brief smiles that winked across Peter’s face, but this time Peter was blank, as blank as John’s voice, and therefore of no help, and so he was forced to answer as if the question had been meant plainly, which it perhaps had.

“Not so much,” he said, and the truth of that answer—its obviousness, its undeniability—was so inarguable and stark that it again felt as if the room had gone still, and that even John was ashamed to have asked such a question. And then David began to try to do what he sometimes did, which was worse, which was to explain himself, to try to give word and form to what his days were. “I was reading—” But, oh, he was spared from further humiliation, because here was their grandfather entering the room, a dark bottle of wine furred in a mouse-gray felt of dust held aloft, exclaiming his triumph—he had found it!—even before he was fully among them, telling Adams they’d be spontaneous, to decant it now and they’d have it with dinner. “And, ah, look, in the time it took me to locate that blasted bottle, another lovely appearance,” he said, and smiled at David, before turning toward the group so that his smile included them all, an invitation for them to follow him to the dining table, which they did, and where they were to have one of their usual monthly Sunday meals, the six of them in their usual positions around the gleaming oak table—Grandfather at the head, David to his right and Eliza to his, John to Grandfather’s left and Peter to his, Eden at the foot—and their usual murmured, inconsequential conversation: news of the bank, news of Eden’s studies, news of the children, news of Peter’s and Eliza’s families. Outside, the world stormed and burned—the Germans moving ever-deeper into Africa, the French still hacking their way through Indochina, and closer, the latest frights in the Colonies: shootings and hangings and beatings, immolations, events too terrible to contemplate and yet so near as well—but none of these things, especially the ones closest to them, were allowed to pierce the cloud of Grandfather’s dinners, where everything was soft and the hard was made pliable; even the sole had been steamed so expertly that you needed only to scoop it with the

spoon held out for you, the bones yielding to the silver’s gentlest nudge. But still, it was difficult, ever more so, not to allow the outside to intrude, and over dessert, a ginger-wine syllabub whipped as light as milk froth, David wondered whether the others were thinking, as he was, of that precious gingerroot that had been found and dug in the Colonies and brought to them here in the Free States and bought by Cook at great expense: Who had been forced to dig and harvest the roots? From whose hands had it been taken?

After dinner, they reconvened in the parlor and Matthew poured the coffee and tea and Grandfather had shifted in his seat, just a bit, when Eliza suddenly sprung to her feet and said, “Peter, I keep meaning to show you the picture in that book of that extraordinary seabird I mentioned to you last week and promised I wouldn’t let myself forget again tonight; Grandfather Bingham, might I?” and Grandfather nodded and said, “Of course, child,” and Peter stood then, too, and they left the room, arm in arm, Eden looking proud to have a wife who was so well attuned to everything around her, who could anticipate when the Binghams would want to be alone and would know how to gracefully remove herself from their presence. Eliza was red-haired and thick-limbed, and when she moved through the parlor, the little glass ornaments trimming the table lamps shivered and jingled, but in this respect she was light and swift, and they had all had occasion to be grateful to her for this knowingness she possessed.

So they were to have the conversation Grandfather had told him they would back in January, when the year was new. And yet each month they had waited, and each month, after each family dinner—and after first Independence Day, and then Easter, and then May Day, and then Grandfather’s birthday, and all the other special occasions for which the group of them gathered—they had not, and had not, and had not, and now here it was, the second Sunday in October, and they were to discuss it after all. The others, too, instantly understood the topic, and there was a general coming-to, a returning to plates and saucers of bitten-into biscuits and half-full teacups, and an uncrossing of legs and straightening of spines, except for

Grandfather, who instead leaned deeper into his chair, its seat creaking beneath him.

“It has been important for me to raise the three of you with honesty,” he began after one of his silences. “I know other grandfathers would not be having this discussion with you, whether from a sense of discretion or because he would rather not suffer the arguments and disappointments that inevitably come from it—why should one, when those arguments can be had when one is gone, and no longer has to be involved? But I am not that kind of grandfather to you three, and never have been, and so I think it best to speak to you plainly. Mind you”—and here he stopped and looked at each of them, sharply, in turn—“this does not mean I plan on suffering any disappointments now: My telling you what I am about to does not mean it is unsettled in my mind; this is the end of the subject, not its beginning. I am telling you so there will be no misinterpretations, no speculations—you are hearing it from me, with your own ears, not from a piece of paper in Frances Holson’s office with all of you clad in black.

“It should not surprise you to learn that I intend to divide my estate among the three of you equally. You all have personal items and assets from your parents, of course, but I have assigned you each some of my own treasures, things I think you or your children will enjoy, individually. The discovery of those will have to wait until I am no longer with you. There has been money set aside for any children you may have. For the children you already have, I have established trusts: Eden, there is one apiece for Wolf and Rosemary; John, there is one for Timothy as well. And, David, there is an equal amount for any of your potential heirs.

“Bingham Brothers will remain in control of its board of directors, and its shares will be divided among the three of you. You will each retain a seat on the board. Should you decide to sell your shares, the penalties will be steep, and you must offer your siblings the opportunity to buy them first, at a reduced rate, and then the sale must be approved by the rest of the board. I have discussed this all with you before, individually. None of this should be remarkable.”

Now he shifted again, and so did the siblings, for they knew that what was to be announced next was the real riddle, and they knew, and knew that their grandfather knew, that whatever he had decided would make some combination of them unhappy—it was only to be a matter of which combination.

“Eden,” he announced, “you shall have Frog’s Pond Way and the Fifth Avenue apartment. John, you shall have the Larkspur estate and the Newport house.”

And here the air seemed to tighten and shimmer, as they all realized what this meant: that David would have the house on Washington Square.

“And to David,” Grandfather said, slowly, “Washington Square. And the Hudson cottage.”

He looked tired then, and leaned back deeper still in his seat from what seemed like true exhaustion, not just performance, and still the silence continued. “And that is that, that is my decision,” Grandfather declared. “I want you all to assent, aloud, now.”

“Yes, Grandfather,” they all murmured, and then David found himself and added, “Thank you, Grandfather,” and John and Eden, waking from their own trances, echoed him.

“You’re welcome,” Grandfather said. “Although let us hope it might be many years still until Eden is tearing down my beloved root shack at Frog’s Pond,” and he smiled at her, and she managed to return it.

After this, and without any of them saying it, the evening came to an abrupt close. John rang for Matthew to summon Peter and Eliza and ready their hansoms, and then there were handshakes and kisses and the leave-taking, with all of them walking to the door and his siblings and their spouses draping themselves in cloaks and shawls and wrapping themselves in scarves, normally an oddly raucous and prolonged affair, with last-minute proclamations about the meal and announcements and stray, forgotten bits of information about their outside lives, was muted and brief, Peter and Eliza both already wearing the expectant, indulgent, sympathetic expressions that anyone who married into the Binghams’ orbit learned to adopt early in their tenure. And then they were gone, in a last round of embraces

and goodbyes that included David in gesture if not in warmth or spirit.

Following these Sunday-night dinners, it was his and his grandfather’s habit to have either another glass of port or some more tea in his drawing room, and to discuss how the evening had unfolded—small observations, only verging on gossip, Grandfather’s slightly more fanged as was both his right and his way: Had Peter not looked a touch wan to David? Did not Eden’s anatomy professor sound insufferable? But tonight, once the door was closed and the two of them were again alone in the house, Grandfather said that he was tired, that it had been a long day, and he was going up to bed.

“Of course,” he’d replied, though his permission wasn’t being asked, but he too wanted to be alone to think about what had transpired, and so he kissed his grandfather on his cheek and then stood for a minute in the candlelit gold of the entry of what would someday be his house before he too turned to go upstairs to his room, asking Matthew to bring him another dish of the syllabub before he did.