To Sell Is Human: The Surprising Truth About Moving Others (6 page)

Read To Sell Is Human: The Surprising Truth About Moving Others Online

Authors: Daniel H. Pink

Tags: #Psychology, #Business

Ferlazzo makes a distinction between “irritation” and “agitation.” Irritation, he says, is “challenging people to do something that

we

want them to do.” By contrast, “agitation is challenging them to do something that

they

want to do.” What he has discovered throughout his career is that “irritation doesn’t work.” It might be effective in the short term. But to move people fully and deeply requires something more—not looking at the student or the patient as a pawn on a chessboard but as a full participant in the game.

This principle of moving others relies on a different set of capabilities—in particular, the qualities of attunement, which I’ll explore in Chapter 4, and clarity, which I’ll cover in Chapter 6. “It’s about leading with my ears instead of my mouth,” Ferlazzo says. “It means trying to elicit from people what their goals are for themselves and having the flexibility to frame what we do in that context.”

For example, in his ninth-grade class last year, after finishing a unit on natural disasters, Ferlazzo asked his students to write an essay about the natural disaster they considered the very worst. One of his students—Ferlazzo calls him “John”—refused. This wasn’t the first time he had done so, either. John had struggled throughout school and had written very little. But he still hoped eventually to graduate.

Ferlazzo told John that he wanted him to graduate, too, but that graduation was unlikely if he couldn’t write an essay. “I then told him that I knew from previous conversations that he was on the football team and liked football,” Ferlazzo said. “I asked him what his favorite football team was. He looked a little taken aback since it seemed off topic—it looked like he had been expecting a lecture. ‘The Raiders,’ he replied. Okay, then, what was his least favorite team? ‘The Giants.’”

So Ferlazzo asked him to write an essay showing why the Raiders were superior to the Giants. John stayed on task, said Ferlazzo, asked “thoughtful and practical questions,” and turned in a “decent essay.” Then John asked to write another essay—this one about basketball—to make up for previous essays he hadn’t bothered to do. Ferlazzo said yes. John delivered another pretty good piece of written work.

“Later that week, in a parent-teacher conference with all of his teachers, John’s mother cried when I showed her the two essays. She said he’d never written one before” during his previous nine years of schooling.

Ferlazzo says he “used agitation to challenge him on the idea of graduating from high school and I used my ears knowing that he was interested in football.” Ferlazzo’s aim wasn’t to force John to write about natural disasters but to help him develop writing skills. He convinced John to give up resources—ego and effort—and that helped John move himself.

Ferlazzo’s wife—the Med to his Ed—sees something similar with her patients. “The model of health care is ‘We’re the experts.’ We go in and tell you what to do.” But she has found, and both experience and evidence confirm, that this approach has its limits. “We need to take a step back and bring [patients] on board,” she told me. “People usually know themselves way better than I do.” So now, in order to move people to move themselves, she tells them, “I need your expertise.” Patients heal faster and better when they’re part of the moving process.

Health care and education both revolve around non-sales selling: the ability to influence, to persuade, and to change behavior while striking a balance between what others want and what you can provide them. And the rising prominence of this dual sector is potentially transformative. Since novelist Upton Sinclair coined the term around 1910, and sociologist C. Wright Mills made it widespread forty years later, experts and laypeople alike have talked about “white-collar” workers. But now, as populations age and require more care and as economies grow more complex and demand increased learning, a new type of worker is emerging. We may be entering something closer to a “white coat/white chalk” economy,

17

where Ed-Med is the dominant sector and where moving others is at the core of how we earn a living.

—

D

oes all of this mean that you, too, are in the moving business—that entrepreneurship, elasticity, and Ed-Med have unwittingly turned you into a salesperson? Not necessarily. But you can find out by answering the following four questions:

1.

Do you earn your living trying to convince others to purchase goods or services?

If you answered yes, you’re in sales. (But you probably knew that already.) If you answered no, go to question 2.

2.

Do you work for yourself or run your own operation, even on the side?

If yes, you’re in sales—probably a mix of traditional sales and non-sales selling. If no, go to question 3.

3.

Does your work require elastic skills—the ability to cross boundaries and functions, to work outside your specialty, and to do a variety of different things throughout the day?

If yes, you’re almost certainly in sales—mostly non-sales selling with perhaps a mix of traditional sales now and then. If no, go to question 4.

4.

Do you work in education or health care?

If yes, you’re in sales—the brave new world of non-sales selling. If no, and if you answered no to the first three questions, you’re not in sales.

So where did you end up? My guess is that you found yourself where I found myself—living uneasily in a neighborhood you might have thought was for someone else. My guess, too, is that this makes you uncomfortable. We’ve seen movies like

Glengarry Glen Ross

and

Tin Men,

which depict sales as fueled by greed and founded on misdeed. We’ve been cornered by the fast-talking commissioned salesman urging us to sign on the line that is dotted. Sales—even when we give it a futuristic gloss like “non-sales selling”—carries a seamy reputation. And if you don’t believe me, turn to the next chapter so I can show you a picture.

3.

From

Caveat Emptor

to

Caveat Venditor

W

hat do people really think of sales? To find out, I turned to an effective, and often underused, methodology: I asked them. As part of the

What Do You Do at Work?

survey, I posed the following question to respondents:

When you think of “sales” or “selling,” what’s the first word that comes to mind?

The most common answer was

money

, and the ten most frequent responses included words like “pitch,” “marketing,” and “persuasion.” But when I combed through the list and removed the nouns, most of which were value-neutral synonyms for “selling,” an interesting picture emerged.

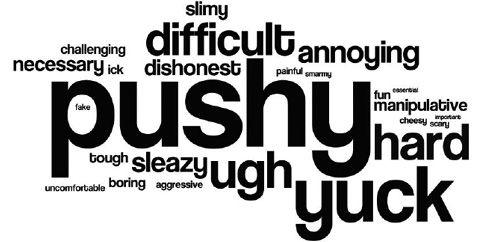

What you see below is a word cloud. It’s a graphic representation of the twenty-five adjectives and interjections people offered most frequently when prompted to think of “sales” or “selling,” with the size of each word reflecting how many respondents used it. For instance, “pushy” was the most frequent adjective or interjection (and the fourth-most-mentioned word overall), thus its impressive size. “Smarmy,” “essential,” and “important” are tinier because they were mentioned less often.

Adjectives and interjections can reveal people’s attitudes, since they often contain an emotional component that nouns lack. And the emotions elicited by “sales” or “selling” carry an unmistakable flavor. Of the twenty-five most offered words, only five have a positive valence (“necessary,” “challenging,” “fun,” “essential,” and “important”). The remainder are all negative. These negative words assemble into two camps. A few reflect people’s

discomfort

with selling (“tough,” “difficult,” “hard,” “painful”), but most reflect their

distaste

. Words like “pushy” and “aggressive” figure prominently, along with a batch of adjectives that suggest deception: “slimy,” “smarmy,” “sleazy,” “dishonest,” “manipulative,” and “fake

.

”

This word cloud, a linguistic MRI of our brains contemplating sales, captures a common view. Selling makes many of us uncomfortable and even a bit disgusted (“ick,” “yuck,” “ugh”), in part because we believe that its practice revolves around duplicity, dissembling, and double-dealing.

To probe people’s impressions further, I asked a related question, one better suited to visual thinkers:

When you think of “sales” or “selling,” what’s the first picture that comes to mind?

(Respondents had to describe their picture in five or fewer words.)

To my surprise, the responses—in overwhelming numbers—took a distinct form. They involved a man in a suit selling a car, generally a used one. Take a look at the resulting word cloud for the twenty-five most popular answers:

The top five responses, by a wide margin, were: “car salesman,” “suit,” “used-car salesman,” “man in a suit,” and our old friend, “pushy.” (The top ten also included both “car” and “used car” on their own.) The image that formed in respondents’ minds was uniformly male. The word “man” even made the top twenty-five. Very few people used the gender-neutral term “salesperson” and nobody answered “saleswoman.” Many respondents emphasized the sociable aspects of sales—with “outgoing,” “extrovert,” and “talker” all making the top twenty-five. Others settled on more metaphorical or literary images, including “shark” and “Willy Loman.” And some people still couldn’t resist offering adjectives: “slick,” “sleazy,” and “annoying.”

It turns out that these two word clouds, taken together, can help us puncture one of the most pervasive myths about selling in all its forms. The beliefs embedded in that first image—that sales is distasteful because it’s deceitful—aren’t so much inherently wrong as they are woefully outdated. And the way to understand that is by pulling back the layers of that second image.

Lemons and Other Sour Subjects

In 1967, George Akerlof, a first-year economics professor at the University of California, Berkeley, wrote a thirteen-page paper that used economic theory and a handful of equations to examine a corner of the commercial world where few economists had dared to tread: the used-car market. The first two academic journals where young Akerlof submitted his paper rejected it because they “did not publish papers on topics of such triviality.”

1

The third journal also turned down Akerlof’s study, but on different grounds. Its reviewers didn’t say his analysis was trivial; they said it was mistaken. Finally, two years after he’d completed the paper,

The Quarterly Journal of Economics

accepted it and in 1970 published “The Market for ‘Lemons’: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism.” Akerlof’s article went on to become one of the most cited economics papers of the last fifty years. In 2001, it earned him a Nobel Prize.

In the paper, Akerlof identified a weakness in traditional economic reasoning. Most analyses in economics began by assuming that the parties to any transaction were fully informed actors making rational decisions in their own self-interest. The burgeoning field of behavioral economics has since called into question the second part of that assumption—that we’re all making rational decisions in our own self-interest. Akerlof took aim at the first part—that we’re fully informed. And he enlisted the used-car market for what he called “a finger exercise to illustrate and develop”

2

his ideas.

Cars for sale—he said, oversimplifying in the name of clarifying—fall into two categories: good and bad. Bad cars, what Americans call “lemons,” are obviously less desirable and therefore ought to be cheaper. Trouble is, with used cars, only the seller knows whether the vehicle is a lemon or a peach. The two parties confront “an asymmetry in available information.”

3

One side is fully informed; the other is at least partially in the dark.