Tokio Whip

Authors: Arturo Silva

a novel by

ARTURO SILVA

Stone Bridge Press â¢

Berkeley, California

Published by

Stone Bridge Press

P. O. Box 8208, Berkeley, CA 94707

TEL

510-524-8732 â¢

[email protected]

â¢

www.stonebridge.com

“Tokio Whip: Warp 'n' Woof,” a helpful appendix to this book and a guide to its creation and understanding, is available at the publisher's website,

www.stonebridge.com

.

Front cover photograph courtesy of Yoshiichi Hara.

Text © 2016 Arturo Silva.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher.

Printed in the United States of America.

p-ISBN: 978-1-61172-033-4

e-ISBN: 978-1-61172-922-1

CONTENTS

Lang hadn't wanted to come to Tokyo; but once he got here â well.

C

HAPTER 2.

Y

URAKUCHOâ

S

HIMBASHI

C

HAPTER 3.

H

AMAMATSUCHOâ

S

HINAGAWA

C

HAPTER 7.

S

HINJUKUâ

S

HIN-

O

KUBO

C

HAPTER 8.

T

AKADANOBABAâ

M

EJIRO

C

HAPTER 11.

N

ISHI-

N

IPPORIâ

N

IPPORI 291

Roberta returned to Tokyo; Lang finished his work â there it is â here they are!

NOTE

Many Japanese names occur in the course of this novel. Most are either people or place names, or the names of things such as food items or pieces of clothing. The reader really need not worry about their pronunciation or meaning â some will be familiar, some are explained in passing, others are not. However, two do require some orientation.

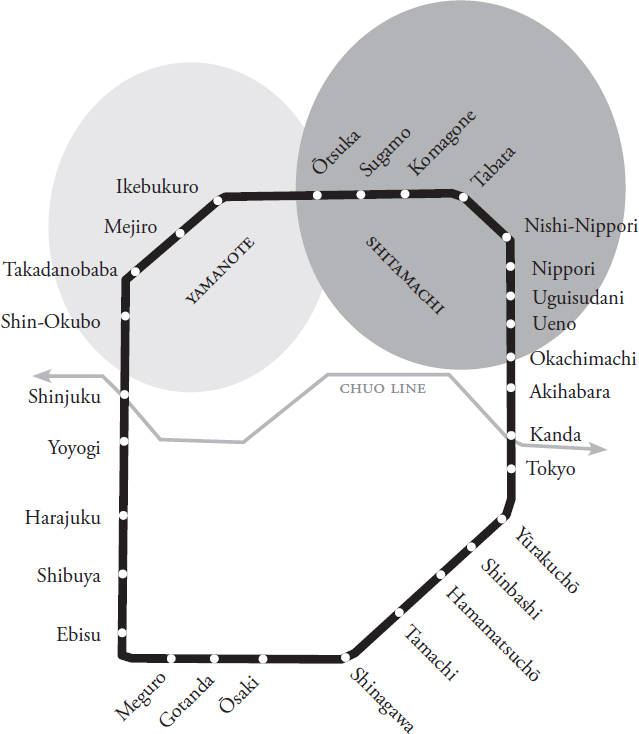

Yamanote

, commonly called “The High City,” is that westward area arcing around Shinjuku, and traditionally the wealthier and more modern side of the city.

Shitamachi

, or The Low City, is the older, more plebian and traditional side of the city, arcing east around the Imperial Palace and extending as far as and beyond the Sumida River. In this book they are also often opposed as the East and West sides of the city â but even those distinctions are questioned, as the reader will see. Yamanote is also the name of the train line that makes a loop around most of the central wards of the city (though not the entire city) â embracing both

yamanote

and

shitamachi

, twenty-nine stations in all, but here reduced to twenty-four. This Yamanote is what is referred to by the titles of the chapters that comprise Parts One A and B of the book.

The Yamanote Line makes a loop through downtown Tokyo, traversing the High City (Yamanote) and Low City (Shitamchi).

Tokyo is a city where one learns to gaze only at the immediate prospect, blotting out what lies beyond.

â Edward G. Seidensticker

Outside and inside abolished, talk can now begin: at last, at last the dialogue.

â Julio Cortázar

Our language can be seen as an ancient city: a maze of little streets and squares, of old and new houses, and of houses with additions from various periods; and this surrounded by a multitude of new boroughs with straight regular streets and uniform houses.

â Ludwig Wittgenstein,

Philosophical Investigations

, I, 18

We drink coffee with cream while suspended over the abyss.

â Andrei Bely

It's funny how some things make you think of other things.

â Carole Lombard

PART ONE (A)

THE YAMANOTE

Chapter 1

KANDAâTOKYO

Lang hadn't wanted to come to Tokyo; but once he got here â well.

we began walking somewhere around sunset

â Hey! This building wasn't here yesterday.

across the city

â Say it again: the two most beautiful words: sunset, â

to Shinjuku and Roberta's party around Midnight

â Better lost in Tokyo than found in any other city.

and then further west, talking our way

into the

Sun-

r

i

s

e

!

***

Rich and strange, strange and rich, Marianne muses, and once more rich and strange. Oh, Tokyo, damn you! Where am I? Here, yes, and one more step â there. Now I'm here, now there. Rich and strange you are, Marianne, a here and there myself. Bless you, Tokyo. Walking in step like a waking dream. A girl in her dreams talking to herself.

***

â

Oh, comeon, it's not modern at all, all this brick, that wood. And look at those dives right under the tracks, that

yakuza

-type over there eyeing me â what a racket!

â

Still, if we can stay steady â

â

As she goes!

â

On yer feet!

â

Aye aye, Sir!

â

Tokyo Station should be just ahead.

But Hiromi does not “stay steady,” thinks a detour will help, and though the tracks are generally still in sight, she and her friends have lost their way. She stares in the window of a shop selling medical equipment â all of it made of glass.

â

Orange Card, IO card, and why “SF Metro” card? â this isn't San Francisco.

â

And mine's all run out, now it really looks like we have to walk.

â

Well, try to enjoy yourself, Dear.

â

Eh?

â

That's what my Granny used to tell me every morning when I left for school.

â

Let's see, she says, as she finds the page in her compact Tokyo map-book. This must be that real old bridge; homeless people sleeping there now around all these banks. My city!

â

And mine!

â

Mine too!

***

Tanizaki's Dream: Orderly thoroughfares, shining, newly-paved streets, a flood of cars, blocks of flats rising floor upon floor, level on level in geometric beauty, and threading through the city elevated lines, subways, street cars. (But see also Tanizaki on Asakusa: “Its constant and peerless richness preserved even as it furiously changes in nature and in its ingredients, swelling and clashing in confusion and then fusing into harmony.”)

***

Van Zandt is himself, that is, as he is now, though in the dream he is back in high school in Amsterdam, where he sees a classmate, Jenny, blonde and thin, whom he wishes he were not too shy to approach. (VZ often has this dream, and it is the one he hates most, because it reminds him of that long period that no one would ever guess now when he was shy and inarticulate, and rarely spoke to a female.) He sees the school auditorium; it is the night of the senior prom (and this scene looks as if it were taken from an American teenage genre film ((VZ in fact never attended any such dance; in fact, had never even known of the thing till he saw

Carrie

.)) ) The prom goes on, people dancing, and Van Zandt feels lonely. Then all the girls are told to get on stage. It's time for “boy's choice,” instead of the usual “ladies' choice.” VZ asks Jenny to dance. They walk away (however much one would think the occasion demanded a dance). She takes his hand. They walk out of the auditorium and in the dark alley she stops and kisses him. He is surprised. They are walking through Akitsu, in Kiyose, in northeastern Tokyo, just there at the border with Saitama Prefecture. There are white box houses with pink motorcycles for Mom and that always mean the suburbs. The suburbs, a Frankenstein for the 1990s, with the rent of a 4LDK two-thirds of a 1LDK just west of the Yamanote. On a wall someone has spray painted the title of a favorite song “

kimi ni mune kyun kyun

” by YMO. There is much greenery, a clear stream â he sees fish in it as he peers from Maebara Bridge. And then in the dream where he sees the long rows of houses that look like military barracks (did he live in one once, see them in a home movie? ((these are private plots)) ), he sees a map made of books, and in a park public art the likes of which one does not usually see in Tokio: a “Peace Monument” (Showa 49), abstract, steps, two monoliths almost meeting as if hands closed in prayer. VZ and Jenny go to the house of some friends. They are no longer in high-school, but as they are now â or as he is and she as how he dreams of a girl whom he hasn't seen in fifteen years. Jenny takes him into a corner and kisses him, forcefully, deeply. Her hand reaches down and grabs his crotch. Then Van Zandt is walking swiftly, muttering to himself, “How could this happen? How could my trip be so suddenly cancelled?” It is another city, another time. He walks into his home; the entire family is there, but everyone is busy and so they ignore him. (Throughout this last scene his siblings are as they are now, and all scurrying about the room.) VZ's mother appears. Her hair is cut very short (like Falconetti's, but that's where any resemblance ends). She rushes up to her son, sobbing, “Why do they all say I'm guilty? What have I done? I'm not guilty. I swear. You believe me, don't you?” And then VZ awakes.

In the background of VZ's dream, as in the following dream, he hears the black death lyrics of Howlin' Wolf: “Smokestack Lightnin' shines like gold / I found my baby layin' on the cooling board // Don't you hear me talkin' Pretty Mama // Don't the hearse look lonesome rollin' 'fore your door / She's gone â oowhoo â won't be back no more.”

In Kazuo's dream he is walking in Akitsu, turns, and there is a valley, and a river below. A group of people are happily swimming, gamboling. They are all strong swimmers, and the image is an almost ideal one of human physical grace. There are some steps, a large rock, a bridge down-river. It is a short, idyllic dream. And then Kazuo wakes.

***

Kazuyoshi Miura: Murder in the Media

With very few exceptions â most notably the Abe Sada story of 1936, known to most people through Nagisa Oshima's film

In the Realm of the Senses

(1976), and the Imperial Bank Robbery of 1948 â murder in Twentieth Century Tokyo has been an unexciting affair. In recent years there have been the usual sushi-knife slashings, the occasional dismembered body parts (in one case, in thirty-four separate bags just around the corner from the author's home), and the fortunately more rare true horror story (infanticide, cannibalism). One pop star (“idol”) did throw herself off of a building â to include suicide for a moment â after being jilted by another singer; that may have been “romantic” of her, but the jilter himself was so uninteresting, so predictably “cute,” hardly worth the adolescent gesture. Even with the brief wave of copycats, that story too soon lost public interest. A much more talented singer, Yutaka Ozaki, took a few pills too many one night mixed with too much alcohol and was found in the street next day near his home â no, contemporary murder has little glamour and less imagination these days in Tokyo.

Perhaps the most interesting modern murder was that of Kazumi Miura, a murder that was allegedly set up by her husband Kazuyoshi. While having some interesting complications, the case is especially compelling for the huge role the media played in it â or roles, for it has doted on Kazuyoshi Miura as much as he has courted it; it has also been attacked by him in court; and eventually it was the media â or one of its representatives â that cracked the case open. The story of Kazuyoshi Miura is a particularly relevant tale for our times.

Los Angeles, November 18, 1981. The clothes importer Kazuyoshi Miura, age 34, and his wife of two years, Kazumi, 28, are on their “second honeymoon” in Los Angeles. (The Miura's have a young daughter.) While taking photos in a parking lot â Miura will claim he just happened to spot a possible advertising location â Kazumi is robbed and shot in the head, and her husband in the leg. Kazumi falls into a permanent coma, and two months later returns to Japan. Within a year of the shooting she dies. Despite some suspicions, the Los Angeles Police Department is helpless â no evidence, no suspects.

On March 31, 1994, Miura, by now 46, is sentenced to life imprisonment for conspiring to murder his wife. He is so judged on circumstantial evidence, the judge saying that it is “logical to assume” that Miura was the mastermind behind the death of Kazumi. The judge describes Miura as being “selfish and cold-blooded,” a man who has shown no signs of remorse over the death of his wife.

The murder plot was simple enough; Miura is said to have hired an employee to do the job, including shooting Miura himself. Miura's testimony however was shot through with holes (if we may be pardoned the expression). To take only one important example: Miura claimed that the assailants fled in a green car; witnesses of the scene â though not of the murder â saw only a white van. The suspected assailant had hired a white van the day before the murder.

Miura is also believed to have made two other attempts on Kazumi's life before his final success. Three months earlier in Los Angeles, Miura had asked a former mistress and porno actress to kill Kazumi in Tokyo in August 1981 by bludgeoning her with a hammer. The actress did so, but Kazumi recovered. He is also supposed to have asked two former employees to kill Kazumi.

With Kazumi's death, Miura collected one hundred-fifty million yen in insurance money.

Apart from the details, Kazumi Miura, sadly, is lost in the story. The murder was one thing; the “follow-up” was another.

Crimes involving Japanese abroad are big news in Japan. While still in Los Angeles, Miura was holding interviews with the press from his hospital bed. He was an immediate media favorite and national hero for the fortitude with which he bore his pain and loss. Like a good Japanese, he even sent letters to President Ronald Reagan, the Governor of California, the Mayor of Los Angeles and the U. S. Ambassador to Japan decrying the violence of the American way of life. He even had photos of his daughter distributed, bearing the caption, “Give Me My Mommy Back!”.

For two years Miura was off scot-free (and rich). In the autumn of 1983, thanks to a tip concerning the insurance payment, a team of reporters from the weekly magazine

Shukan Bunshun

began to investigate him. The following January it ran a series of articles detailing Miura's past, which included: three marriages; seven years in prison for more than one hundred petty robberies; assorted other crimes (arson, assault, possession of a sword); and the story of a former employee and lover who had suddenly “disappeared” after having received 4.3 million yen in a divorce settlement. (The money had been taken out of her account shortly after she had “left the job” in March 1979; her body was later found in May 1979 in Los Angeles)

.

The police reopened the case.

The articles were called “Bullets of Suspicion.” Miura responded with a book called “Bullets of Information.” From then on there was no let up. Articles and interviews flowed back and forth. Miura courted as much as he evaded the media. It was a mutual affair. He was said to have charged anywhere from five to fifty million yen per interview. He signed an exclusive contract with one television network to film his latest marriage â he was engaged within six months of Kazumi's death â in Bali in April 1985. He even played himself in a movie. As one Los Angeles detective remarked, Miura was “pouring gasoline on the fire.”

Finally in September 1985 Miura and the porno actress/would-be murderess were arrested for the August 1981 murder attempt. The arrest was broadcast live on television. (As many arrests are in Japan, the police tipping the media off shortly before.) The woman confessed. (She received two-and-one-half years.) In May 1987 Miura was finally sentenced to six years. In October 1988, after further investigations by the LAPD, Miura was charged in Tokyo with the murder of Kazumi. (So too was his accomplice, the man in the white van who did the actual shooting. He was eventually acquitted for insufficient evidence.) Now the Miura-media tug-of-war grew in fury. He began to sue newspapers and magazines for libel. And not only did he defend himself, he usually won. He even sued one paper for writing that he sued too often! By summer 1994 he was involved in 230 different suits. Of the first hundred cases, of which he won seventy, he was awarded more than thirty-three million yen in damages.

Unrepentant and litigious to the end, Miura blames all his misfortunes on the very media whose willing darling for a time he was.

***

Yes, I believe it's perfectly alright if he loves the city as he says he does. Who am I to doubt him, or to deny him? No love can be judged. I can't agree with Roberta, for example, who simply calls him “mad.” But then perhaps she is intending a pun. I don't know, but in this case I do doubt. No, I only wonder what the nature of his love is (again, without in any way judging it). It can, after all, be as rough a city as it can be a tender one. And we know that while he usually treats us all rather fairly â I really have few complaints, and most of those small â he can, well, have his moods. But can his love match the city, then? Can his love be strong, consistent over the years and adapt to the changes that must inevitably occur? Is he a faithful partner? (He does say this has been his most successful relationship â his relationship with the city, that is.) Is he capable, by my standards, of loving the city lightly, softly? It does seem to me sometimes that he is a bit too aggressive in his declarations of love, as if he were afraid of any doubt making itself known. Perhaps even an unconscious doubt. He seems occasionally to press his love, to forward his suit, to crush the city to his heart. Well, we shall see. In the meantime, too, the evidence of his love lies all about us. â So the kindly Kazuo.