Tolstoy (11 page)

Authors: Rosamund Bartlett

It is intriguing that Tolstoy also has something in common with the founder of the revived Moravian Church, the eccentric Count Nikolaus Ludwig von Zinzendorf, whose commitment to serving the poor led him to allow a group of Brethren to form a community on his land in the 1720s. Zinzendorf ended up leaving his position with the Saxon royal court in Dresden, and turning his back on his title and aristocratic lifestyle to live a simple life and devote himself to serving God. It was he who brought unity to the new village established by the immigrants, which led to them adopting a 'Brotherly Agreement', and he was key to the Brothers one day experiencing a spiritual transformation which led them to love one another. Tolstoy, of course, never believed he was starting a new church and he also dispensed with all sacraments. But in his appeal to ecumenical ideas of fellowship, and in his preaching of the merits of a simple life of service, he aligned himself with the ideals of the Moravian Brotherhood. As a pioneer ant brother, he would, moreover, definitely have approved of their motto: 'In essentials, unity; in non-essentials, liberty; and in all things, love'.

3. ORPHANHOOD

I congratulate you, my dear Lyova, and also your brothers and sister, I wish you good health and diligence in your studies, so that you never cause any unpleasantness for dear Auntie Tatyana Alexandrovna, who works so hard for us. Mitya and Lyova, we went on a wonderful walk the other day, we all went to Sparrow Hills, and drank tea there. Since the weather is so good, I imagine you were in Grumant. I hope you have lots of fun. I send love to my dear Masha...

Letter from Nikolay Tolstoy in Moscow to Lev, Dmitry and Masha Tolstoy in Yasnaya Polyana, on the occasion of Lev's tenth birthday, August 1838

1

LOOKING BACK OVER HIS LIFE

when he was in his seventies, Tolstoy described the 'innocent, joyful, poetic period' of his childhood as lasting until he was fourteen.

2

Only the first seven of those fourteen years were truly cloudless, however. In the second seven, Tolstoy lost his father, his grandmother and his aunt, was temporarily separated from his elder brothers, and moved three times. The last upheaval resulted in a relocation several hundred miles from home. In a very real sense, the most idyllic part of Tolstoy's childhood began its decline with the first of those relocations, when the reassuring bucolic surroundings of Yasnaya Polyana were exchanged for the intimidating new world of metropolitan Moscow. It is these years, and the ones immediately following, which are amongst the least documented in what is generally an over-documented life. With a few exceptions, Tolstoy's memoirs essentially come to a halt with the family's departure from Yasnaya Polyana, although his trilogy

Childhood, Boyhood, Youth

is also a wonderful source of atmospheric detail about his early years, since it is clearly rooted in his own experience, despite it being a work of fiction.

Tolstoy's father moved his family to Moscow in January 1837 for the sake of the elder boys' education. Lev was only eight years old, but his eldest brother Nikolay was now fourteen, and already preparing for his university entrance. The relocation was a major undertaking, since the family was numerous, comprising the five Tolstoy children, two wards, two aunts, Nikolay Ilyich and his mother, and was accompanied by a full complement of thirty servants.

3

The journey north lasted two days, and involved a caravan of seven carriages, plus a special closed sleigh for grandmother Pelageya Nikolayevna. To make her feel safe, she was chaperoned by two of the family's manservants, who were forced to endure freezing temperatures and stand on the runners all the way.

4

The children took it in turns to sit with their father, and when they finally drove into Moscow, it was Lev who was lucky enough to be sitting next to him as he proudly pointed out the churches and prominent buildings they could see through the carriage windows.

5

Arriving from the south, the Tolstoys would have driven through the colourful merchants' quarter, the Zamoskvorechie ('Beyond the Moscow river') and so would have first seen a profusion of onion-domed churches. The merchants were traditionally the most pious section of the Russian population, and the Zamoskvorechie had the greatest concentration of churches in Moscow, which was already a city renowned for its large number of churches. Nikolay Ilyich had rented a handsome house with a mezzanine set back from the street in a spacious courtyard, and after driving through the Zamoskvorechie, the Tolstoy family caravan would have turned west and arrived in a quiet residential area near to the Moscow river. It was to this part of Moscow that Tolstoy returned when his own family moved to the city in the 1880s.

In old age, Tolstoy had only dim memories of these first few months in the old capital. The city had by now fully recovered from the traumatic events of 1812, following an intense period of reconstruction, and the new urban surroundings would have seemed overwhelming for a boy used to a tranquil rural environment; he now found himself in the midst of buildings and strangers, and no longer the centre of attention. Nikolay was busy preparing for the university, and the Tolstoy children rarely saw their father, who had engaged as many as twelve tutors (including a dancing teacher) to keep his children busy, at an imposing annual cost of 83,000 roubles.

6

Meanwhile Nikolay Ilyich had become embroiled in a lawsuit over his purchase of the estate of Pirogovo from Alexander Temyashev, the man who had begged him to bring up his illegitimate daughter Dunechka. Temyashev was stricken with paralysis shortly after the contract was signed, and his relatives wanted the deeds declared null and void. As far as Tolstoy's father was concerned, however, he was now its legitimate owner. Nikolay Ilyich's health had been frail ever since his gruelling time in the army during and after the Napoleonic invasion. The stress of having to pick up the pieces and take responsibility after his father's bankruptcy, dismissal from the governorship of Kazan and untimely death had not helped. Tolstoy's father also had a tendency to drink too much. In 1836 he had written to a friend to tell him he was on a strict diet and taking medicines after experiencing the shock of coughing up a lot of blood.

7

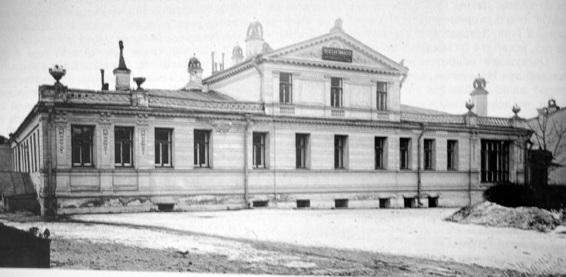

2. The house in Plyushchikha Street, Moscow, to which Nikolay Ilych Tolstoy brought his mother, sister andfive children in 1837

In June, a few months after arriving in Moscow, Nikolay Ilyich was obliged to go urgently to Tula to try to deal with the crisis which had blown up over his purchase of Pirogovo. Taking only his faithful servants Petrusha and Matyusha, he covered the distance in half the time it had taken his family to travel to Moscow earlier that year. That also had a deleterious effect on his health.

8

The following evening, shortly before his forty-third birthday, he suffered a massive lung haemorrhage and stroke while walking down the street in Tula, and died that same day. Rumours flew about that he had been poisoned by his servants, since all his money appeared to have been stolen, but Tolstoy was later not inclined to believe this story.

9

Nikolay Ilyich's unexpected death was understandably a huge shock to his family. His sister Aline and his eldest son Nikolay travelled down from Moscow, and they buried him next to his wife Maria Nikolayevna in the village cemetery next to Yasnaya Polyana. For young Lev, his father's death was the most significant event of his childhood, and for a long time he kept expecting to see him one day on the streets of Moscow.

10

Babushka

Pelageya Nikolayevna, who had doted on her son Nikolay, never really recovered, and the loss was also acutely felt by his sister Aline, and perhaps above all by his distant cousin Toinette, for whom he had been the centre of her world.

It was Aline who now became guardian to the five Tolstoy children, with assistance from one of her late brother's friends, Sergey Yazykov, who had an estate in Tula province. Sergey Yazykov was also Lev's godfather, but his involvement was fairly minimal from the start, and even that decreased over time. As well as assuming responsibility for the children's education, Aline now had to occupy herself with the crude practicalities of selling cattle and organising harvests, since she was now in charge of the considerable income that came from the five disparate properties the Tolstoy children had inherited. Each estate came with a farm, and each farm had complicated accounts that needed to be carefully checked, obliging Aline to deal with uncouth stewards and bookkeepers who could often be truculent and dishonest. Aline was also now responsible for the welfare of the hundreds of serfs who belonged to the Tolstoy family. It was their toil, after all, which enabled the Tolstoys to maintain a comfortable lifestyle. All in all, it was a job for which someone so naive and otherworldly was ill-qualified, to say the least, as Aline's chief interests, after all, were spiritual, not material. Nikolay Ilyich had done some intricate and crafty manoeuvring in order to enable his family to live in the manner to which it had become accustomed in Moscow as well as in the country, but he left his financial affairs in a perilous state at the time of his death. All Aline could see were debts.

11

And then there was the still-unresolved lawsuit, which would drag on for several more years before finally being resolved in the Tolstoys' favour.

The Tolstoy children remained in Moscow throughout the hot summer months following their father's death, when otherwise they would probably have returned to Yasnaya Polyana. Aline was fortunate to be assisted by Aunt Toinette in caring for them. It was Toinette, for example, who took the children to the Bolshoi Theatre for the first time later that autumn. They sat in a box, and as an old man Tolstoy remembered that he had not immediately realised that he should not be looking straight across to the boxes opposite but sideways, down to the stage.

12

Even the children's redoubtable grandmother now took a hand in their upbringing. Prospère Saint-Thomas had been engaged as French tutor for the elder boys, and three days after her son's death Pelageya Nikolayevna decided to invite the fair-haired Frenchman from Grenoble to become resident governor to her grandchildren, replacing their kindly but not terribly competent German tutor Fyodor Ivanovich, who was consequently demoted. Being impressed by all things French, Pelageya Nikolayevna imagined Saint-Thomas would become the male authority figure that the children needed. The small, wiry Frenchman was certainly dynamic, but Tolstoy bridled at his self-importance and vanity, and he was also not impressed by his grandiloquent rhetorical flourishes.

13

Saint-Thomas was also a harsh disciplinarian who forced his pupils to beg forgiveness for misdemeanours on their knees. Worst of all was the moment when he locked the young Lev up and threatened to punish him with the rod. In terms of its significance, the incident was certainly not on a par with his father's death, but it nevertheless left a very deep impression on Tolstoy - so much so that some sixty years later he recalled in his diary the humiliation and misery of overhearing his family's laughter and merriment while he was locked up 'in prison'. In his memoirs, he went so far as to date his lifelong horror of violence back to this ordeal.

14

It is telling that Tolstoy should have dwelled on this incident. In 1908 Lenin would famously characterise the 'tearing off of masks' as a hallmark of Tolstoy's fiction and it seems that, at nine years old, Tolstoy was already capable of seeing through his French tutor's pretentious veneer. Even though it was precisely at this point that he began to enjoy studying, his already obstinate and headstrong nature made him resent moreover submitting to the authority of a person he did not respect.

15

Later on, he would resent submitting to any authority.

The friction in Tolstoy's relationship with Saint-Thomas may have been caused by an awareness at some level that he possessed a superior intellect, but his mental acuity was not always on show, and certainly not on the day he tried to fly. It was more probably Tolstoyan

dikost

which impelled him to go up to the classroom on the mezzanine floor one day and take a running jump out of the window. He claimed afterwards that he had wanted to do something unusual and surprise everybody. Since everybody was at table, however, wondering where he was, they remained oblivious — until the mystery of young Lev's absence was solved by the cook, who had seen him hurtling towards the ground through the kitchen window. As it turned out, Tolstoy was blessed with a strong constitution. He lost consciousness briefly and suffered some concussion, but was fully restored to health after sleeping solidly for eighteen hours.

16