Traveling Soul (31 page)

Authors: Todd Mayfield

As the camaraderie grew, the road band spent downtime joking with my father, maybe asking what new songs he was working on or just

hanging out in his hotel room. They had nicknames for each otherâAndré was “College Boy” because of the erudition of his speech, my father was “Bucky Beaver” because of his big teeth, and Melvin was “Fattenin' Frogs for Snakes.” That last one was a favorite of road manager Robert Cobbins. Melvin always had his eye on a girl at each show, but every time he tried to bring her in the dressing room, Lucky would say, “No, you have to leave the girl outside. Talk to her after you change your clothes.” Lucky would hurry up and get dressed, and by the time Melvin came out, Lucky would be gone with the girl. Melvin would shake his head and say, “Fattenin' frogs for snakes.” Every time Robert saw Melvin, he'd say, “Here comes Fattenin' Frogs for Snakes.” The camaraderie wasn't constant though, and many times my father would find a girl of his own and disappear.

Still, the band gelled. “Curtis was not hard to work for at all, but you definitely had to know your part,” André says.

You couldn't do something obviously wrong, and there had to be dynamics. The rule was if you couldn't hear the vocals, you were playing too loud. At the time, there weren't sound crews and semis pulling up. It was tour buses and tired musicians setting up their own equipment. The sound systems weren't great, and sometimes you couldn't hear properly. There would be no monitors on stage, and you'd hear the echo back of the house speakers, which was disconcerting if you're trying to play time. What happens is, you didn't spread yourself out too far on stage. You set up close to each other to play like an ensemble. Even when you saw James Brown, they wouldn't set up far apart. They'd be like an arm's length away from each other. That's for communication. That was very special for Curtis.

As the year wore on, more heavy changes came over the world. In July, humanity broke its bond with Mother Earth and put its first footprints on the moon. In August, the biggest gathering of peace-loving hippies

in history took place on Yasgur's farm near Woodstock, New York. The Woodstock concert marked the climax of the 1960s. Thirty-two of the decade's most influential acts performed for four hundred thousand people, and the concert was captured in a film that encapsulated the spirit of the timesâthe escapism into drugs, the belief that music and love could stop war, the certainty that the youth (at least, white youth) would change the world.

Hendrix closed the festival with a new band he called Gypsy Sun and Rainbows, later shortened to Band of Gypsys. On a cold Monday morning, he ripped into a version of the “Star Spangled Banner” that became a haunting epitaph for the era. He put every moment of the brutal, wonderful decade through his guitar, making the national anthem by turns tragic, gorgeous, and jarringâsometimes it sounded like war, like sirens wailing and bombs dropping; sometimes it sounded like rock 'n' roll, like hallucinogenic drugs and free love; sometimes it sounded like chaos, like riots and assassinations.

The next month, the Chicago Seven went on trial for inciting the riot at the DNC the year before, and a new group called the Weathermen committed acts of terrorism intended to cripple the American government. Meanwhile, the movement remained without leadership except for the Panthers, who crumbled under pressures from within and without.

Anger in the militant black community surged as conservative white America became more entrenched against it. The pendulum King had started swinging to the left in the late 1950s, toward black people's rights, toward equality, now swung almost all the way back. The Panthers' violent image only helped it swing faster. Even liberal whites began distancing themselves.

My father tuned into these events as closely as he tuned into the radio as a child. They affected him just as much. He despaired at watching the peaceful movement he had once believed in suffer a bitter, violent death. He never felt his job was to keep that peaceful movement going; rather

he felt called to reflect what the people around him felt and experienced. These people felt increasingly furious, paranoid, depressed, abandoned. Dad needed to write about these changes, but he didn't feel right doing it with the Impressions. He needed to get something new across. He hinted at it with “We're a Winner,” but he had to censor himself while recording that song so ABC would release it. He needed to grow, but he also needed Curtom to grow. One way to increase sales without adding new acts was to do what record companies had been doing to singing groups for decades. It was the exact thing Vee-Jay did to the original Impressionsâpull the lead singer from the group and give him a career of his own while the band continued without him.

Marv had long been in my father's ear about that. “Everyone makin' it [is] a singer-songwriter,” he repeated, over and over again. “You're an artist, you should go out on your own.” Marv angled for more control, and Dad wanted to make him vice president of Curtom. Eddie disagreed, feeling Marv should work his way up the ranks. Dad leaned toward Marv, driving a bigger wedge between him and Eddie. “I suggested to him that he just focus on producing and writing,” Eddie said. “Marv told him that he should start a solo career ⦠I feared that Curtis would burn out in short time.” It was a difficult decision, but my father went with the advice of a man he hardly knew over that of his closest friend and business partner.

As the ninety-day tour for

Young Mods

wound down, the Impressions arrived at Madison Square Garden for one of the last shows of the year. The bill that night in New York included Jerry Butler and the Four Tops. André had left the group to play with Jerry, but since the Impressions hadn't found a solid replacement, he stayed on the stage and performed two sets. The next day Jerry had off, so André went with the Impressions to a gig in Buffalo, New York. It was the dead of winter; the year was dwindling to a close. When they arrived in Buffalo, five feet of snow blanketed the ground. The gig went off, but afterward, the Impressions were mad as hell about something and left Lucky, André, Melvin, and

Craig at the auditorium. They had no way to the airport and the theatre was locked, so they stood in the middle of Buffalo, snow up to their chests, facing the prospect of lugging their equipment to God knew where. By some miracle, a man with a station wagon who had seen the show offered them a ride. On the way to the airport, he asked if they wouldn't mind stopping by a club.

They wound through the snowy Buffalo streets until they stopped at the clubâa real down-home type of place where a local band sweated it out on a small stage. The station-wagon man talked to the locals, said he had the Impressions' band in the club, and before they knew it, the guys were on stage playing. They jammed from eleven at night until four in the morning. They played every song they knew, made things up on the spot, and brought the roof down.

As the night petered out, leaving a few stragglers nursing their beers in the hazy predawn, Lucky, André, Melvin, and Craig crammed back into the station wagon and rode to the airport. They gave the man some money, walked inside dead tired, and each boarded a plane to a different city. It was the last time they'd perform together as the Impressions.

It was a time of endings. The decade sputtered out in a grotesque spasm of bitterness and violence. Free love, flower power, Woodstock, moon landings, marches, movements, assassinations, drugsâthe whole vicious, beautiful thing was unraveling. Life was unraveling for my father too. Around this time, my mother finally decided to leave. She tried to put the house up for sale, only to realize her name wasn't on the deed.

My father also grew further from Fred and Sam than ever. These were the most important relationships of his life so far, and the longest lasting. Indeed, he might have spent more time with Fred and Sam than he did with my mother or any woman he'd ever known. Somewhere in his mind, though, he knew he needed to leave the group. He didn't say anything yet, but as 1969 came to a close, he felt the need to free himself, to reinvent himself, to speak his mind like never before.

When the story about the Impressions' West Coast tour appeared in

Rolling Stone

near the end of 1969, Alexander ended it by saying, “[Curtis] is writing the songs of the coming black middle class. The songs of aspirations. A good home, a nice car, decent neighbors, money, educated kids, travel, security. You can't knock it until you've had the opportunity to reject it.”

In his defense, Alexander couldn't have known what my father was about to do. And he was rightâthe Impressions' music was aimed mostly at the “coming black middle class.” It was about pushing, and moving, and creating a better tomorrow. But my father's mind had moved somewhere else.

At twenty-seven years old, he was about to change the game again.

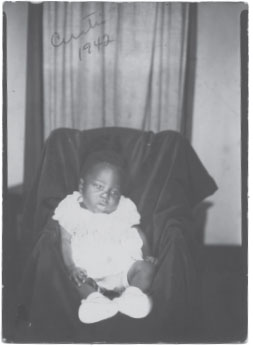

Curtis as a newborn, Chicago 1942.

AUTHOR'S COLLECTION