Trevor (3 page)

Authors: James Lecesne

Tags: #Trevor, #Trevor Project, #James Lecesne, #Lady Gaga, #bullying, #LGBT, #It Gets Better, #gay, #lesbian, #bisexual, #transgender, #questioning, #youth, #young adult, #seven stories press, #triangle square edition

Six

The show went

on without a hitch. Tanya was brilliant and her rendition of “Anything Goes” got a standing ovation at both performances. Jed Steckler came down with a wicked case of flu and as a result the audiences never got to enjoy his hilarious portrayal of Public Enemy #13 Moonface Martin. Instead I had to step in at the last moment and double as both Moonface and Lord Oakleigh. It was exhaustingâand terrifying. But people came up to me afterwards to tell me that they were utterly amazed, not only because I could play both parts so adroitly and make all of the quick changes, but also because in scenes where both characters appeared, I was able to slip seamlessly between the two without losing my place or my footing. A tour de force, they called it. I was pretty proud.

It turned out to be a good thing that Pinky had dropped out of the show. If he had remained in the chorus, he would have been changing his costume backstage while I did my shtick onstage, and he never would have had the chance to see my performance from out in the auditorium. Besides, after two weeks of rehearsal it didn't seem as though he was ever going to get the dance steps down and do them in a convincing or artistically pleasing manner. I looked for him afterwards, but I totally understood why he didn't hang around. He had said on more than one occasion that he had already endured plenty of the cast's barbed musical-comedy comments and self-congratulatory looks. Everyone was pissed at him for dropping out at the last minute, everyone except for Tanya and me. However, he did call me at home after our cast party to tell me what he thought of the show.

“You are the real star, man.”

“But what about Tanya?” I asked him as I was removing my makeup.

“Screw Tanya,” he replied bitterly. “She's a stuck-up bitch who thinks too much of herself for her own good.”

I couldn't believe my ears; I was so touched. He really thought I was better than Tanya!

He went on to tell me that the situation at home was not good. Apparently his father had been on a rampage for the past twenty-four hours; he had turned the Faraday household upside downâliterally. I didn't want to pry, but I did ask him if he was safe. He told me that he was for the time being because he was calling me from the crawlspace up in the attic and that was why he had to whisper.

“If anything happened to you, Pinky,” I said, trying to hold back my tears, “I wouldn't be able to go on. I really wouldn't.”

“Yes, you would,” he said. “You'd be surprised how quickly people get over even the worst stuff.”

A chill went up my spine because at that moment I realized that I was going to have to prove to Pinky that he was a person worth not getting over quickly.

“No,” I told him. “I wouldn't.”

And then very quietly, so that his father wouldn't hear him, we sang a few bars of the song “Anything Goes” together.

The world has gone mad today

And good's bad today,

And black's white today,

And day's night today,

When most guys today

That women prize today

Are just silly gigolos

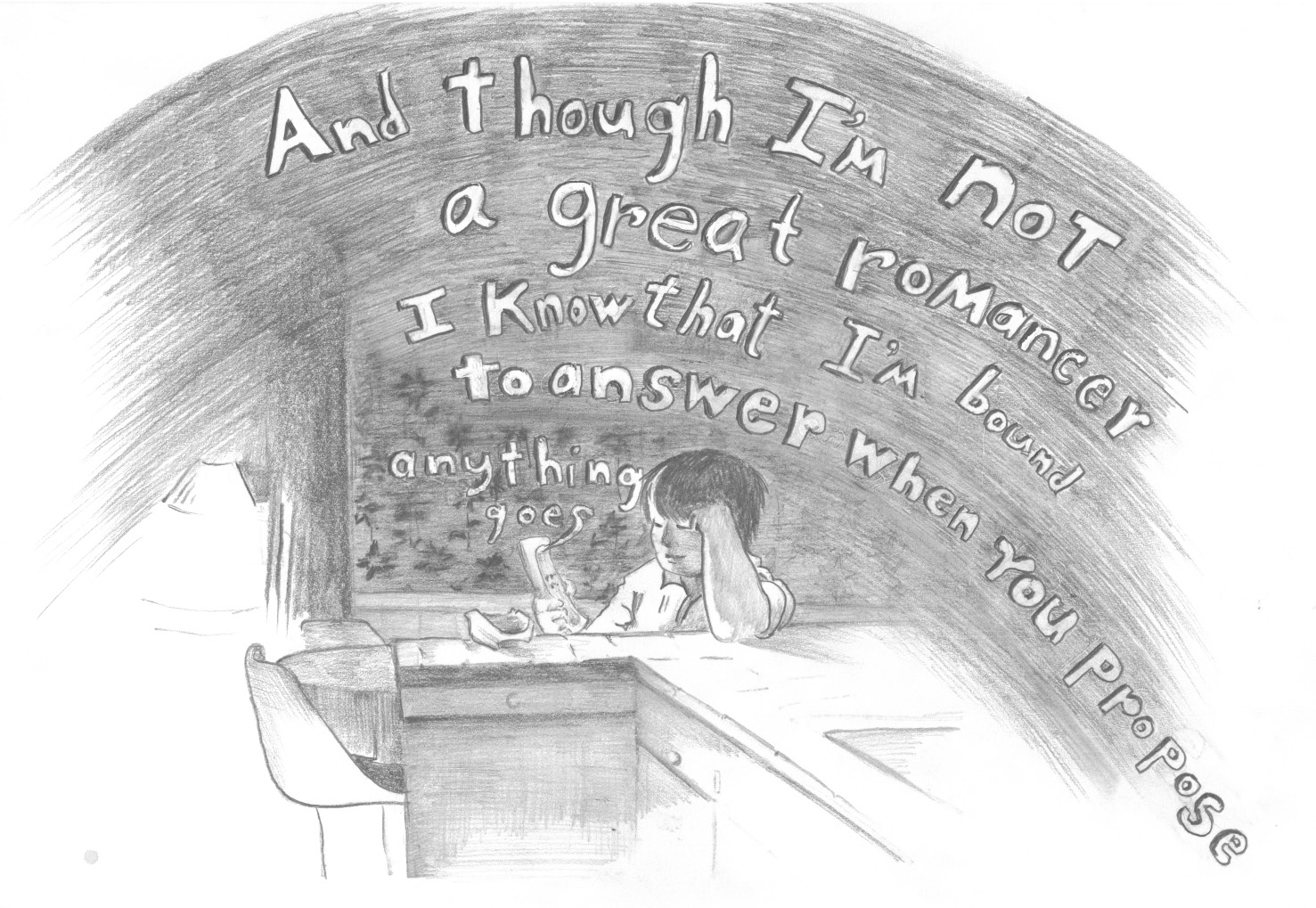

And though I'm not a great romancer

I know that I'm bound to answer

When you propose,

Anything goes.

The next night, I called Pinky on his cell to make sure he was okay and that his father hadn't done anything crazy. When I got no response I texted him several times, sent him a message on Facebook, and then finally called his home phone. His stepmother answered. She was super polite with me, but firm. She said Pinky couldn't speak to me, and I should not try contacting him anymore. I was so stunned I didn't even ask her why. I just said “Okay” and then I hung up.

I sat down and wrote Pinky a long letter telling him what had happened, because I knew he knew nothing about it and was probably being held hostage by his father or something. I hardly slept all night.

The next day at school, I gave Pinky the letter. He took it from me without saying anything and then acted as though he was late for class, which he was not because the bell hadn't even rung yet.

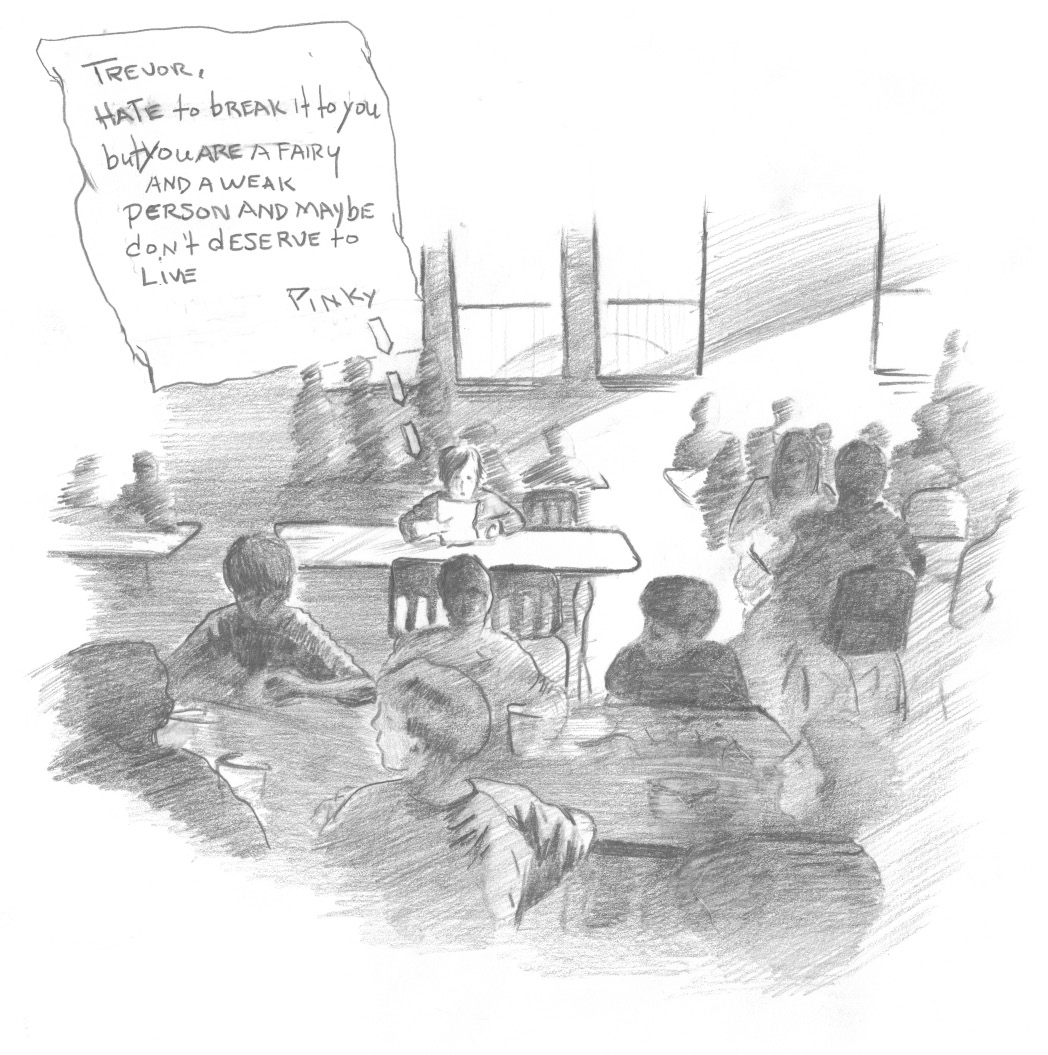

At lunch, he gave me a letter back; it was written on lined paper that had been torn from a spiral notebook and though the writing was nearly illegible, I could make out every word. It said that I was a fairy, a weak person and maybe didn't even deserve to live.

This was devastating news. The worst part of it was that I felt so utterly alone. There was no one in whom I could confide. Katie and Zac had always been jealous of my friendship with Pinky, and they probably would celebrate the fact that Pinky was finally out of the picture. Dad was away on business, and besides, he wouldn't have understood the problem. And Mom? She would have told me that maybe Pinky wasn't as good a friend as I had thought he was and then suggested that I put the whole thing behind me, call up Zac, and invite him for a sleepover like old times. How could I have told her what was really in my heart? What could she have said if I told her that I didn't want old times or that I wanted Pinky? What nobody could understand, what I could hardly understand myself, was that the one person I wanted to talk to about all this was Pinky. And that just wasn't going to happen. I couldn't exactly walk up to him at school and ask him the one thing I was dying to knowâdid this mean that he and I were not best friends anymore? Is that what he was trying to tell me? What had I done wrong?

Seven

I

broke down

and told Katie Quinn what happened between Pinky and me, which is to say that I told her that I didn't know what happened between Pinky and me or why he had stopped talking to me. She mentioned that she overheard some of his friends talking about me behind my back.

“What'd they say?” I asked her.

“I shouldn't say,”

“Tell me,” I pleaded. “I should know.”

“You don't want to know.”

“Katie, please. Whatever they said can't be worse than what I'm imagining in my head right now.”

“Okay. So the guys were saying you walk like a girl.”

Let me just say that this was so much worse than anything that I could have ever imagined in my head. In fact, I felt as though I could have killed myself over this. Naturally, I denied it. I told Katie that I did not walk anything like a girl. I did not! She gave me a sad smile, and then I heard myself saying, “Wait. Do

you

think I walk like a girl?”

“No,” was her response, “of course not.”

I suggested that the best way to prove that we were both right was to give her a demonstration. Bad move. When I was finished, I turned around and I could tell by the look on her face that something was wrong.

“What?” I asked her.

“Nothing.”

I went straight home and threw out my black leotard and sequined cape and all of my glitter makeup. No way was I ever going to dress up as Lady Gaga ever again. That phase of my life was over.

After that I decided to spend some time doing push-ups and also sitting in front of the mirror in my room taking a good hard look at myself. Something was wrong with me and it was definitely showing. But what? No matter how long I stood there in front of the mirror, no matter how hard I stared at my own reflection, I couldn't see the thing that was making me seem different from everybody else. My life had become an obvious tragedy; ironic that I was the only person who couldn't see it.

The next day at school Pinky stopped saying

hey

to me in between classes, and he seemed to be going out of his way to avoid me in the cafeteria. English class was a particular kind of torture because I was forced to see him for forty minutes, and he refused to look at me or acknowledge my existence. No one knew how deeply I suffered over this because I was determined to keep it to myself. This went on for more than a week, and the whole time I just wanted to know what had happened to my friendship with Pinky. Where did it go? What had I done to upset him? Was it because I walked like a girl? Maybe there was something I could do to make it better. But what?

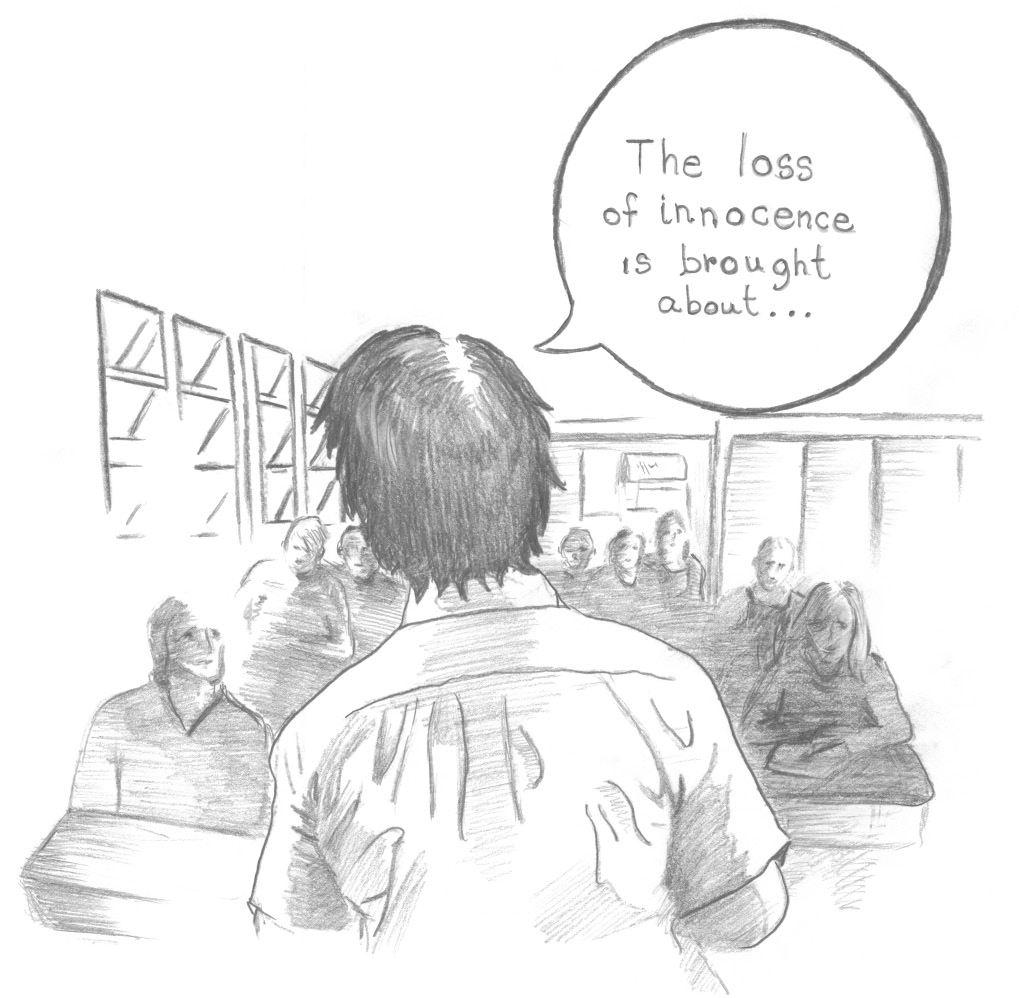

Then Mr. Kienast asked me to read aloud from my report on the short story. This was like a form of torture specially designed to humiliate and embarrass me. As I made my way to the front of the class, I could hear the kids whispering behind my back.

That's the kid who has a crush on Pinky Faraday.

This was the longest walk I had ever taken in my life. I stood there facing the class with my stupid paper, and even though I knew it wasn't possible, I hoped that maybe this was all just a bad dream. When I realized that it wasn't a bad dream, I hoped instead that I might drop dead in front of the entire class. When that didn't happen, I swallowed hard and began.

“I chose for my topic

The Loss of Innocence as Reflected in Literature

. Here's what I wrote:

“The loss of innocence is brought about because of an experience with no explanation. The character must be involved in the experience and must experience the loss. Must be hurt. Must survive. The experience must be potent enough to be remembered and must create a subtle change in the character . . .”

Mr. Kienast gave me an A for my report. No one could tell that I copied it all from a book. Pinky continued to ignore me, and for the rest of the day I was officially invisible.

Eight

M

om was cleaning

my room, and she just

happened

to read something that I'd been typing on my computer, a confidential email that I could have sent to my BFFâif I'd had a BFF. But since I do not have a BFF, or even a close friend in whom I could confide my deepest and most intimate feelings, the email was just idling on my screen unreadâuntil Mom came along.

She had a fit and then we had an all-out fight. I told her that my private life was none of her business and maybe I was crazy but it seemed to me that I ought to be able to have the freedom to express my own private thoughts in the privacy of my own room and on my own “personal” computer. She claimed that I was still too young to have any kind of a life that didn't concern her, personal, private, or otherwise.

“I'm your mother,” she said louder than was absolutely necessary. “And in case you haven't noticed, I am in charge of your life.”

To express my opposition to this extremely unfair point of view and to protest against people feeling that they had the right to read emails without the say-so of the person who wrote them, I attempted to run away to San Francisco. I did not leave a note. I simply packed a bag and snuck out through the garage. Unfortunately, I only got as far as the bus station. Mom dragged me back home so that she could tell me that she was very, very, very worried about me (she used three

very

's). She sat me down in the living room and announced that we needed to have a talk.

“A talk?” I said.

“Yes,” she replied. “For example, do you think you might be depressed?”

“Um,” I remarked. “I'm not sure. I don't think so.”

She then went on to explain that depression can often go undetected, but if left untreated it could become a serious problem in the life of a teen. Apparently, drug abuse and self-loathing are possible next steps when depression is involvedâand worse.

“Worse?”

She didn't care to elaborate. Instead she told me that she couldn't even begin to imagine what it must be like for me to be a teenager living in the modern world. When she was my age, the world was an entirely different place and there were no such things as the Internet or Facebook or cell phones or texting or tweeting, and computers hadn't even been invented yet.

“But how did you communicate with your friends?” I asked her.

“By speaking to them,” she replied. “Either face-to-face or on the telephone.”

She explained that when she was growing up, they only had one telephone and it was located in the hallway of the house. Her sisters, her mother and father, everyone knew all about her business. And though at the time she resented the fact that she was not allowed to have secrets, she had come to realize that her family was able to help her simply because they always knew what she was going through.

“So that's why I was wondering,” Mom said. “Are you going through something I should know about?”

When I didn't respond, she pulled out my art history notebook, opened it, and showed me the inside cover. There, alongside a pencil sketch of some random fruits and an earthenware jug, Pinky's name was doodled in script. Each letter was carefully shaded and colored. Then she slowly turned the pages, showing me other examples of Pinky's name written over and over in all the margins.

“That's Katie's notebook,” I blurted out. “She loaned it to me. It's not mine, if that's what you're thinking.”

Mom's shoulders dropped and she let out a sigh of either defeat or relief. As she stood up, she handed me the notebook and said: “Well, let's make sure that Katie gets it back.”

And then to signal that our talk was over, she leaned over and took me in her arms. She hugged me hard for like a full minute until I said, “Mom? I kind of can't breathe.” I don't think she knew that I was lying to her about the notebook, but I'm pretty sure she knew I wasn't telling the truth.

After that, I was bigger than TV in our house, and that's saying a lot. Mom kept a close eye on me, and Dad was pretty interested in my moods and whereabouts as well. I was like the star of my own reality series, except for the fact that the only people watching were my mother and father. And I wasn't on just once a week; I was broadcasting every day, all day.

Dad came into my room one evening, sat on my bed, and asked if there was maybe something I wanted to discuss with him. I watched as little beads of sweat began to form on his brow. His leg twitched and though he tried to hold my gaze, his eyes kept shifting toward the door as though he was sizing up the exits in case of an emergency. I knew that Mom had put him up to this and I could tell that he wanted to go back downstairs and watch his show on TV. I took pity on him and said, “I'm good.” He gave me a pat on the shoulder and told me that any time I needed to talk with him, mano-a-mano, he was available 24-7.