Trick or Treatment (14 page)

Read Trick or Treatment Online

Authors: Simon Singh,Edzard Ernst M.D.

The origins of homeopathy

Unlike acupuncture, homeopathy’s origins are not shrouded in the mists of time, but can be traced back to the work of a German physician called Samuel Hahnemann at the end of the eighteenth century. Having studied medicine in Leipzig, Vienna and Erlangen, Hahnemann earned a reputation as one of Europe’s foremost intellectuals. He published widely on both medicine and chemistry, and used his knowledge of English, French, Italian, Greek, Latin, Arabic, Syriac, Chaldaic and Hebrew to translate numerous scholarly treatises.

He seemed set for a distinguished medical career, but during the 1780s he began to question the conventional practices of the day. For instance, he rarely bled his patients, even though his colleagues strongly advocated bloodletting. Moreover, he was an outspoken critic of those responsible for treating the Holy Roman Emperor Leopold of Austria, who was bled four times in the twenty-four hours immediately prior to his death in 1792. According to Hahnemann, Leopold’s high fever and abdominal distension did not require such a risky treatment. Of course, we now know that bloodletting is indeed a dangerous intervention. The imperial court physicians, however, responded by calling Hahnemann a murderer for depriving his own patients of what they deemed to be a vital medical procedure.

Hahnemann was a decent man, who combined intelligence with integrity. He gradually realized that his medical colleagues knew very little about how to diagnose their patients accurately, and worse still these doctors knew even less about the impact of their treatments, which meant that they probably did more harm than good. Not surprisingly, Hahnemann eventually felt unable to continue practising this sort of medicine:

My sense of duty would not easily allow me to treat the unknown pathological state of my suffering brethren with these unknown medicines. The thought of becoming in this way a murderer or malefactor towards the life of my fellow human beings was most terrible to me, so terrible and disturbing that I wholly gave up my practice in the first years of my married life and occupied myself solely with chemistry and writing.

In 1790, having moved away from all conventional medicine, Hahnemann was inspired to develop his own revolutionary school of medicine. His first step towards inventing homeopathy took place when he began experimenting on himself with the drug Cinchona, which is derived from the bark of a Peruvian tree. Cinchona contains quinine and was being used successfully in the treatment of malaria, but Hahnemann consumed it when he was healthy, perhaps in the hope that it might act as a general tonic for maintaining good health. To his surprise, however, his health began to deteriorate and he developed the sort of symptoms usually associated with malaria. In other words, here was a substance that was normally used for curing the fevers, shivering and sweating suffered by a malaria patient, which was now apparently generating the same symptoms in a healthy person.

He experimented with other treatments and obtained the same sort of results: substances used to treat particular symptoms in an unhealthy person seemed to generate those same symptoms when given to a healthy person. By reversing the logic, he proposed a universal principle, namely ‘that which can produce a set of symptoms in a healthy individual, can treat a sick individual who is manifesting a similar set of symptoms’. In 1796 he published an account of his

Law of Similars

, but so far he had gone only halfway towards inventing homeopathy.

Hahnemann went on to propose that he could improve the effect of his ‘like cures like’ remedies by diluting them. According to Hahnemann, and for reasons that continue to remain mysterious, diluting a remedy increased its power to cure, while reducing its potential to cause side-effects. His assumption bears some resemblance to the ‘hair of the dog that bit you’ dictum, inasmuch as a little of what has harmed someone can supposedly undo the harm. The expression has its origins in the belief that a bite from a rabid dog could be treated by placing some of the dog’s hairs in the wound, but nowadays ‘the hair of the dog’ is used to suggest that a small alcoholic drink can cure a hangover.

Moreover, while carrying his remedies on board a horse-drawn carriage, Hahnemann made another breakthrough. He believed that the vigorous shaking of the vehicle had further increased the so-called

potency

of his homeopathic remedies, as a result of which he began to recommend that shaking (or

succussion

) should form part of the dilution process. The combination of dilution and shaking is known as

potentization

.

Over the next few years, Hahnemann identified various homeopathic remedies by conducting experiments known as

provings

, from the German word

prüfen

, meaning to examine or test. This would involve giving daily doses of a homeopathic remedy to several healthy people and then asking them to keep a detailed diary of any symptoms that might emerge over the course of a few weeks. A compilation of their diaries was then used to identify the range of symptoms suffered by a healthy person taking the remedy – Hahnemann then argued that the identical remedy given to a sick patient could relieve those same symptoms.

In 1807 Hahnemann coined the word

Homöopathie

, from the Greek

hómoios

and

pathos

, meaning similar suffering. Then in 1810 he published

Organon der rationellen Heilkunde

(

Organon of the Medical Art

), his first major treatise on the subject of homeopathy, which was followed in the next decade by

Materia Medica Pura

, six volumes that detailed the symptoms cured by sixty-seven homeopathic remedies. Hahnemann had given homeopathy a firm foundation, and the way that it is practised has hardly changed over the last two centuries. According to Jay W. Shelton, who has written extensively on the subject, ‘Hahnemann and his writings are held in almost religious reverence by most homeopaths.’

The gospel according to Hahnemann

Hahnemann was adamant that homeopathy was distinct from herbal medicine, and modern homeopaths still maintain a separate identity and refuse to be labelled herbalists. One of the main reasons for this is that homeopathic remedies are not solely based on plants. They can also be based on animal sources, which sometimes means the whole animal (e.g. ground honeybee), and sometimes just animal secretions (e.g. snake poison, wolf milk). Other remedies are based on mineral sources, ranging from salt to gold, while so-called

nosode

sources are based on diseased material or causative agents, such as bacteria, pus, vomit, tumours, faeces and warts. Since Hahnemann’s era, homeopaths have also relied upon an additional set of sources labelled

imponderables

, which covers non-material phenomena such as X-rays and magnetic fields.

There is something innately comforting about the idea of herbal medicines, which conjures up images of leaves, petals and roots. Homeopathic remedies, by contrast, can sound rather disturbing. In the nineteenth century, for instance, a homeopath describes basing a remedy on ‘pus from an itch pustule of a young and otherwise healthy Negro, who had been infected [with scabies]’. Other homeopathic remedies require crushing live bedbugs, operating on live eels and injecting a scorpion in its rectum.

Another reason why homeopathy is absolutely distinct from herbal medicine, even if the homeopathic remedy is based on plants, is Hahnemann’s emphasis on dilution. If a plant is to be used as the basis of a homeopathic remedy, then the preparation process begins by allowing it to sit in a sealed jar of solvent, which then dissolves some of the plant’s molecules. The solvent can be either water or alcohol, but for ease of explanation we will assume that it is water for the remainder of this chapter. After several weeks the solid material is removed – the remaining water with its dissolved ingredients is called the

mother tincture

.

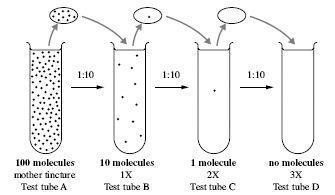

The mother tincture is then diluted, which might involve one part of it being dissolved in nine parts water, thereby diluting it by a factor of ten. This is called a 1X remedy, the X being the Roman numeral for 10. After the dilution, the mixture is vigorously shaken, which completes the potentization process. Taking one part of the 1X remedy, dissolving it in nine parts water and shaking again leads to a 2X remedy. Further dilution and potentization leads to 3X, 4X, 5X and even weaker solutions – remember, Hahnemann believed that weaker solutions led to stronger remedies. Herbal medicine, by contrast, follows the more commonsense rule that more concentrated doses lead to stronger remedies.

The resulting homeopathic solution, whether it is 1X, 10X or even more dilute, can then be directly administered to a patient as a remedy. Alternatively, drops of the solution can be added to an ointment, tablets or some other appropriate form of delivery. For example, one drop might be used to wet a dozen sugar tablets, which would transform them into a dozen homeopathic pills.

At this point, it is important to appreciate the extent of the dilution undergone during the preparation of homeopathic remedies. A 4X remedy, for instance, means that the mother tincture was diluted by a factor of 10 (1X), then again by a factor of 10 (2X), then again by a factor of 10 (3X), and then again by a factor of 10 (4X). This leads to dilution by a factor of 10 x 10 x 10 x 10, which is equal to 10,000. Although this is already a high degree of dilution, homeopathic remedies generally involve even more extreme dilution. Instead of dissolving in factors of 10, homeopathic pharmacists will usually dissolve one part of the mother tincture in 99 parts of water, thereby diluting it by a factor of 100. This is called a 1C remedy, C being the Roman numeral for 100. Repeatedly dissolving by a factor of 100 leads to 2C, 3C, 4C and eventually to ultra-dilute solutions.

For example, homeopathic strengths of 30C are common, which means that the original ingredient has been diluted 30 times by a factor of 100 each time. Therefore, the original substance has been diluted by a factor of 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000, 000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000. This string of noughts might not mean much, but bear in mind that one gram of the mother tincture contains less than 1,00 0,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 molecules. As indicated by the number of noughts, the degree of dilution is vastly bigger than the number of molecules in the mother tincture, which means that there are simply not enough molecules to go round. The bottom line is that this level of dilution is so extreme that the resulting solution is unlikely to contain a single molecule of the original ingredient. In fact, the chance of having one molecule of the active ingredient in the final 30C remedy is one in a billion billion billion billion. In other words, a 30C homeopathic remedy is almost certain to contain nothing more than water. This point is graphically explained in Figure 2. Again, this underlines the difference between herbal and homeopathic remedies – herbal remedies will always have at least a small amount of active ingredient, whereas homeopathic remedies usually contain no active ingredient whatsoever.

Figure 2

Homeopathic remedies are prepared by repeated dilution, with vigorous shaking between stages. Test tube A contains the initial solution, called the mother tincture, which in this case has 100 molecules of the active ingredient. A sample from test tube A is then diluted by a factor of ten (1X), which leads to test tube B, which contains only 10 molecules in a so-called 1X dilution. Next, a sample from test tube B is diluted by a factor of ten again (2X), which leads to test tube C, which contains only 1 molecule. Finally, a sample from test tube C is diluted by a factor of ten for a third time (3X), which leads to test tube D, which is very unlikely to contain any molecules of the active ingredient. Test tube D, devoid of any active ingredient, is then used to make homeopathic remedies. In practice, the number of molecules in the mother tincture will be much greater, but the number of dilutions and the degree of dilution is generally more extreme, so the end result is typically the same – no molecules in the remedy.

Materials that will not dissolve in water, such as granite, are ground down and then one part of the resulting powder is mixed with 99 parts lactose (a form of sugar), which is then ground again to create a 1C composition. One part of the resulting powder is mixed with 99 parts lactose to create a 2C composition, and so on. If this process is repeated 30 times, then the resulting powder can be compacted into 30C tablets. Alternatively, at any stage the powder might be dissolved in water and the remedy can be repeatedly diluted as described previously. In either case, the resulting 30C remedy is, again, almost guaranteed to contain no atoms or molecules of the original active granite ingredient.