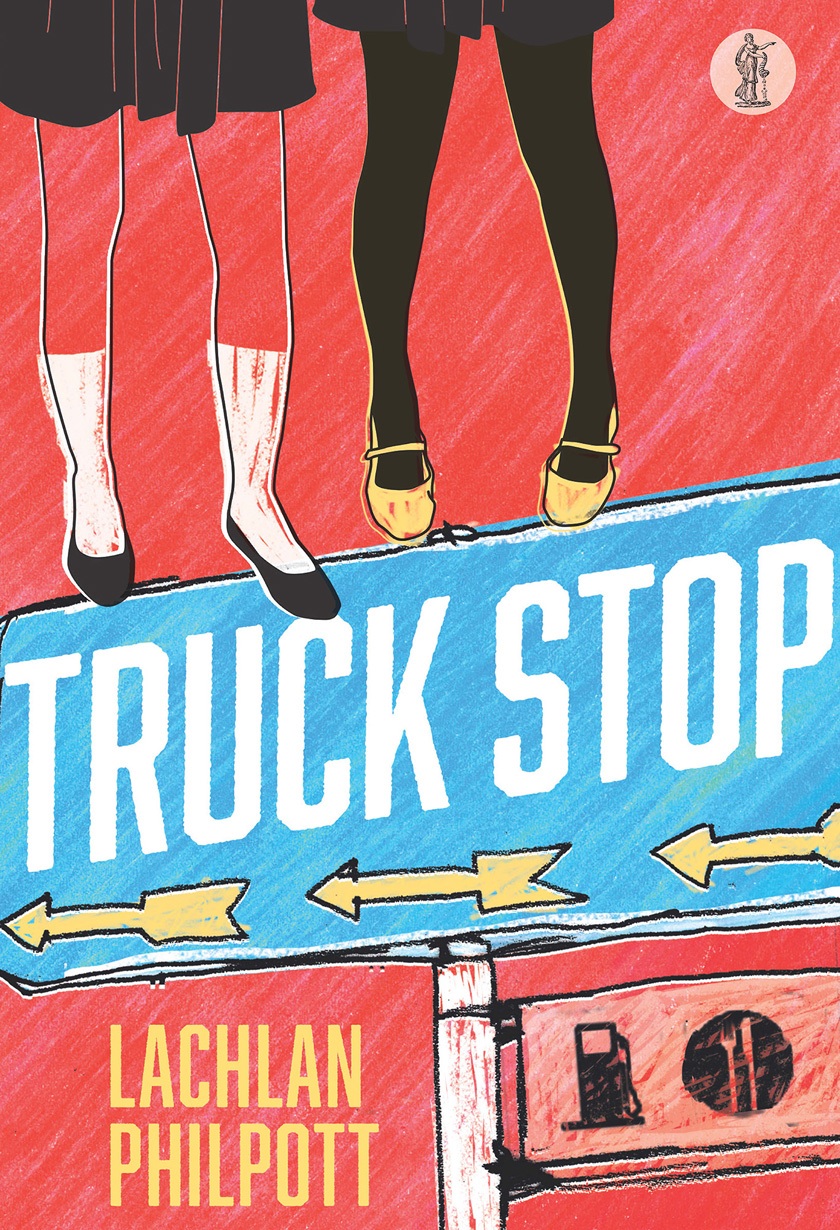

Truck Stop

Authors: Lachlan Philpott

Playwright's Biography

LACHLAN PHILPOTT is a theatre writer, director and teacher. He graduated from UNSW (BA Hons Theatre and Film), The Victorian College of the Arts (Post-Grad Dip, Directing Theatre) and NIDA Playwrights' Studio. He was Artistic Director of Tantrum Theatre in Newcastle, writer-in-residence at Red Stitch in Melbourne and the Literary Associate at ATYP.

His plays have been performed across Australia as well as Ireland, the UK and USA. His plays include

Air Torture

,

Bustown

,

Bison

,

Catapult

,

Colder

,

Due Monday

,

Running Under the Sprinkler

and

Truck Stop.

Lachlan's play,

Silent Disco

,

won the 2009 Griffin Award and the Stage Award at the 45th annual AWGIE Awards in 2012.

For Katrina

INTRODUCTION

I realised something profound about playwrights when I had the privilege of being part of a forum with Lachlan Philpott at the National Institute of Dramatic Art (NIDA)âorganised by their Head of Playwriting, Jane Bodie in 2011. It was something that perhaps I had always known but never seen so clearly as I did that evening in Sydney's Kensington: playwrights are angry. And it was Lachlan who made it plainâhe spoke with force and vigour about the compulsion to write drama, an impulse fuelled by real anger about the world that confronts his characters.

In my experience it's often been the case that playwrightsâcurious, sensitive and thoughtful types, great observers with prodigious memories, wicked senses of humour and ethnographic earsâonce they start to enter the worlds of their plays, or recall the conditions out of which a play of theirs has emerged, they often become tetchy, cranky or just plain angry. I don't know enough novelists, poets or screen-writers to make an observation about all writers, but in my neck of the creative woods playwrights create when their internal infernos burst into the maelstrom of competing voices that are their plays. I am not suggesting that playwriting is all uncontrolled rancour, but I do contend that anger is a powerful motivating factor for playwrights as they look back, around and forward, and then begin to write. That plays rely on conflict seems a reductive truismâtheatre's great value is as a crucible for molten, chaotic humanity, humanity rendered into art by a playwright's principled fury.

And playwrights take nothing for grantedâevery commonplace convention, unchallenged principle, social nicety, unnoticed glance, misspoken utterance, all are grist for their mill, all present opportunities to cut to a character's tormented core. They do this to show us suffering and striving, anguish that reveals greater truths and ultimately gives audiences a meaningful experience. Of course playwrights have intellectual, journalistic and poetic impulses but there's something inexorable and undeniable about the visceral link between emotion, memory, passion, story and audience. If you ever have the pleasure of meeting Lachlan Philpott you will think I am the mad oneâbut dwelling just below his cheeky and charming carapace is a sharp-eyed witness, a belligerent decrier of injustice and a deep, sometimes pugilistic, thinker on discrimination, disenfranchisement and the politics of everyday living.

Truck Stop

reveals Lachlan's interest in giving voice to those on the margins of the Australian city. The setting for

Truck Stop

is literally on the edge of Sydney's vast conurbations, a last stop before a sparsely populated interior of immense distances. His characters struggle to be heard in a society and culture that has little respect for what they have to say, or especially, for the way they say it. This is a play that creates a forum for their voices to emerge in all their contradictory impulses, rage and joy. Lachlan presents quotidian worlds of casual violence, sexism, racism and class division all the while crafting characters of real grace and dignity. He also upturns the all-too-familiar Australian notion of an endless relaxed, articulate and comfortable middle class. And that's a remarkable feature of the playâwhile the playwright may be fired up by inequality and deprivation, the play is not a bilious political tirade, or worthy tract of moral redemption, but a drama alive with ambiguity and complexity, itself an incitement to further discourse.

Coming to playwriting from actor training and high school teaching Lachlan has a particular gift for the distillation of real voices. The transmission of marginalised voices is a political act in his workâto speak difficult, sometimes unpalatable, truths about disadvantage, rebellion, aberrance and othernessâand this begs interesting questions about authenticity and authority. For quite some time towards the end of the twentieth century theatre-makers were perplexed by the question of who had the right to tell certain stories. Could men write believable women characters? Could the middle aged accurately put words in the mouths of the young? Could, or even should, other classes try to represent the working class? Or was that in itself an act of colonisation, theft or repression? Indeed can the rational possibly speak of recklessness or anarchy? These are questions further complicated by notions of a work's authenticity. If a play is penned by an ex-school teacher mightn't it inevitably obscure and misunderstand the argot of the young? And wouldn't that same play also potentially (however subtly) portray authority figures as venerable battlers, everyday heroes struggling to help their messed-up charges, young people the play actually patronised and condescended to?

Truck Stop

places young women at its heart, overcoming such niggling doubts and problematics by presenting multiple points of view using varied vocal registers. The characters describe their own worlds with their own words and the narration tells the story of key character decisions, decisions that are often self-defeating. That Lachlan has listened very carefully to the polyphony around him is evident. There is a genuine grittiness and accuracy to this language, but also a richness and sophistication. These characters are poetic and inarticulate, chatty and powerfully silent, intimate, yet resist easy explanation. Lachlan writes roles actors want to play because of their intricacy, loquaciousness and inner fires. Such characterisation allows certain issues to be airedâthe alienation of the young, dispossession, the failing public education project, desensitisation to basic humanity, the perceived boredom of the suburbs, family trauma, the widening gap between the rich and the poor, the manifold responsibilities of those in authority, the seduction and danger of alcohol and drugs, the thin line between sexual experimentation and exploitationâthrough the prism of the experiential.

One of the key metaphorical systems at work within the play is referred to directly at the opening and the closing of the playâprotection. The play dramatises rich questions about whose job it is to protect the almost legalâshifting the locus from the more common âwhy', to the more pragmatic âhow'. Young adults are smart and they know a great deal but most would agree they still need to be sheltered, or learn how to begin to best shield themselves. The play opens with a seemingly unprovoked playground fight and we watch as the three âSKANKS' increasingly abandon the safe and the sensible, with all reasonable safeguards failing or wilfully being cast asideâand indeed we are even protected from the truck-stop incidents themselves until the final pages. Over the course of the play Sam, Kelly and Aisha oscillate in the twilight between childhood and adulthood, naïvety and invulnerability, fierceness and fragility. Sam and Kelly love hating their lives and Aisha watches her new friends spiral out of control, but what can, should or must she do? And this rich dramatic question is thrown squarely at usâwhat would we do? What should we do? Young girls are trafficked at truck stops, how could this happen in Australia? And what if it's their choice? If we are morally or ethically challenged, emotionally distraught or just simply appalled, this is a play that seems to suggest that our response might need to move beyond the knee-jerk disciplining of young women or politician's insistent and simplistic calls for law and order solutions to a deeper systemic re-thinking of schooling, socialisation and community services.

One final quality worth noting about this play is its form. One of the most difficult aspects of storytelling is matching content with form; that is, how best to let the actual construction of the storyâplot and characters and their articulation of their worldâbe informed by and reflect the guts of the story itself? This is something that Lachlan works very hard to get right. This is a play that, typically for Lachlan, takes on questions about who tells stories and who controls the lives of the young. As a result, the stories are narrated by the subjects themselvesâsometimes in unison and sometimes solo. That this is a modern play is obvious (ordinary people, swearing, pop songs and so on), but this is especially so in the way Lachlan uses both mimesis and diegsis to let the character tell their own stories. Through suggestion, nuance and fine detail, powerful denotation and precise connotation this story poses questions about how truths are constructed, witnessed and felt. Scenes are set, events are narrated and attitudes illustrated through the characters' own words and their mutable subjectivities, subjectivities literally under construction but also under attack, subject to endemic violence, systems failure and psychic disintegration. As the characters' public and private voices are shared with us, Lachlan frames a meta-narrative about which stories are being told and to whom. Not all plays look like this on the page and Lachlan uses character voices to do all the work. He uses this access to language to increase our intimacy with the characters and their worlds but also uses it to hold us at bay, just as the language of officialdom diffuses, decentres and discombobulates. Language is our friend but it also wounds, blinds and evades.

And ultimately that's what makes theatre so compelling: intimacy and evasion, knowing and unknowing, the gut response and the urge to analyse. Further, this hints at why anger is so important in the genesis of theatreâthe initiating impulse that connects the rational and the furious, the diagnostic and the affecting, the social survey and the immersive, all synthesised in the controlled polyphony of drama. Playwrights write out of anger because something matters to themâand when it strikes a chord it clearly matters to many of us.

Truck Stop

uses theatre to put issues of real social importance on stage without bombast or pomposity. Lachlan achieves this by putting real characters in impossible and impossibly familiar situations. We watch and laugh and squirm as they variously confront the recognisable, the difficult and the appalling, making understandable but ultimately disastrous choices. The social and political conditions that make this possible have made the playwright angry, and we feel the power of this anger through the characters and the story. And perhaps as a result we begin to look at the world anewâand maybe even, as Brecht instructed us in

The Measures Taken

, to change the world. It needs it.

Chris Mead

May 2012

Chris Mead is Literary Director at Melbourne Theatre Company.