True Crime (19 page)

Authors: Max Allan Collins

Stege gave me a look like I was a candidate for the loony bin. “Don’t be ridiculous—one of my men has already been to the morgue and shook hands with the corpse. It’s Dillinger all right.”

“It doesn’t look like Dillinger.”

“Plastic surgery,” Stege said, repeating the by-now-familiar litany.

“This whole elaborate setup might’ve been staged to put a patsy in Dillinger’s place, and let the real Dillinger ride off into the sunset.”

“Poppycock.”

“Well, if you feel that strongly about it, Captain…”

“No,” Stege said, shaking his head solemnly, “John Dillinger’s dead. No getting around that. But I aim to find out who put him on the spot…and that includes those crooked East Chicago bastards and Anna Sage and Polly Hamilton.”

“Be my guest.”

He walked toward the door and I followed him. We stopped by the door to the bathroom.

“Is this the commode?” he asked.

“Yeah.”

“Mind if I use it?”

“It’s out of order. Best I can do is a chamber pot.”

“Ah, never mind. It’ll keep. Thanks for the information, Heller. Thanks for the names of the two women. Very helpful. We’ll want to talk to them as soon as possible.”

“Right.”

I opened the door for him and, as an afterthought, he turned and offered me his hand. Surprised, I shook it.

Then he walked like a little general down the hall with the burly plainclothes man in attendance. Off to do battle with the East Chicago police; and to find a bathroom.

I closed and locked the door. Opened the bathroom door and Polly Hamilton, fists on her hips, was burning at me.

“You gave him my name!”

“Did you think it was going to be a secret? The dead man had your picture in his watch, you know.”

“I—I forgot he had that picture…”

“Well, you were at the scene when he was killed. Lots of people saw you. Come on out of that bathroom, Polly.”

She did. She looked forlorn. But pretty.

“I can’t go home. They’ll be waiting.”

“Face the music, or better, go see the feds. They’ll probably shield you.”

She looked up and her eyes did a little dance, like maybe she was remembering something Anna Sage told her along the same lines.

Then she got angry with me, or mock-angry. There was some coquettishness in it.

“Why did you tell him all that?” she wanted to know.

“He’s a cop and he asked me.”

“Oh, you’re such a shit.”

“I thought you had special memories of our night together?”

That made her smile; I still liked her smile.

“I need a place to stay,” she said. “No one would think of looking for me here…”

I was tempted. I admit I was tempted.

But I said, “Try the YWCA,” and pushed her out the door. Hoping Stege was long gone by now.

Before I shut the door she stuck her tongue out at me, and said, “Fuck you.” A strange combination of childishness and adultness. Or is that adultery?

Then I went back to the desk and sat. Looked at the federal wanted poster for Dillinger spread out there, where Stege had left it. His irony was a little heavy-handed, too. Looked at my watch. It was after one.

I called her anyway.

“Helen,” I said into the phone. “Did I wake you? Is that offer for me coming over tonight still open?”

“Yes,” Sally said.

The next afternoon, around three, I was sitting in my shirt sleeves having a bagel and a glass of cold milk in the deli-restaurant below my office. Milk was almost never my drink of choice, but coffee was out of the question—the day was steaming hot, so who the hell needed coffee?

I hadn’t been upstairs yet, having just got back from Sally’s. She’d been good to me last night—we didn’t talk at all; in fact, we didn’t do anything except sleep together—just sleep. And it was exactly what I needed.

What I didn’t need this afternoon was a reporter, but suddenly that’s exactly what I had: Hal Davis, of the

Daily News

, a little guy with a big head—by which I don’t mean he was conceited: he had a big head, literally, a size too big for his smallish frame. He stood grinning in front of me in shirt sleeves and bow tie and gray hat. He was one of those guys who would always seem to be about twenty-two years old. He was easily forty.

“I been looking for you,” he said.

“Sit down, Davis, you’re making me nervous.”

He sat. “You’re a hard man to find.”

“You seem to’ve found me.”

“Pretty wild carryings-on at the morgue last night.”

“I saw the papers.”

He told me about it anyway. “I don’t know how the word got out so fast, but there they were, before the body was even cold, swarming like flies. Couple thousand sweaty souls crow-din’ around the morgue like they were waiting for Sally Rand to go on.”

He meant nothing personal by that; Sally and I hadn’t made the gossip columns yet.

“And that son of a bitch Parker scooped us all,” he said, shaking his head with admiration.

He meant Dr. Charles D. Parker, one of numerous assistants to the coroner’s pathologist, J. J. Kearns. Parker, however, also happened to be a stringer for the

Trib

, covering hospitals and the morgue for ’em. Somehow Parker had got tipped to the shooting early enough on to be able to beat the body to the morgue, where he wheeled a receiving cart up to the door and waited for John Dillinger to arrive.

Soon the meat wagon delivered Dillinger—and exclusive

Trib

coverage of the morgue end of the story—to Parker.

“Got to hand it to that bastard,” Davis conceded. “Hell of a piece of work.”

I took a bite of bagel.

Davis cleared his throat. “I hear you were at the Biograph last night.”

“So were a lot of people.”

“Garage mechanics sitting on their stoop and old ladies hanging out their windows ’cause of the heat. Not trained observers like you, Heller. Your version of the shooting could be a corker.”

“Gee whiz, aw shucks. I’m real flattered, Davis. Now can I finish my bagel?”

T

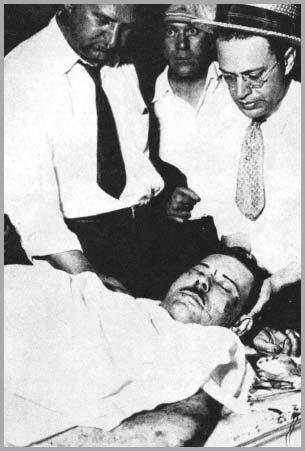

HE BODY AT THE MORGUE

“Hell, I’ll buy you another! How ’bout giving me your eyewitness account. For old times’ sake.”

“What old times are those? When you dredged up the Lingle case in your coverage of my part in the Nitti hit? Get fucked, Davis.”

He smiled. “A newsman knows he’s doing a good job when people resent him. You can’t hurt my feelings, Heller, don’t even bother trying.”

“You’re short.”

He stopped smiling. “

You

get fucked, Heller.”

I gulped my milk. “Every rag in town this morning, including yours, had a dozen eyewitness accounts of the Biograph shooting. This is old news. Why bother?”

Davis waved that off. “Dillinger dying’s gonna be front-page fodder for days, maybe weeks. Besides, the bozos we got eyewitness stories from came in after the show started; you were there for the whole picture, and the featured attractions to boot.”

“What’s in it for me?”

He shrugged facially, “How ’bout a double sawbuck.”

“I don’t think so, Davis.”

“What

do

you want?”

My curiosity got the better of me. “Were you at the inquest?”

“Yeah,” he said, shrugging, with his body this time.

“Anything interesting come out?”

“What’s interesting is what

didn’t

come out. Excuse me.” He went up to the deli counter and got a cup of coffee, and came back and told me about the inquest.

Coroner Walsh himself had presided, at the Cook County Morgue on Polk Street, and had gone first into the little formaldehyde-reeking basement room where the corpse was displayed on a tray draped with a towel, nude but for tags on his toes. The body, that is, not Walsh, who was a big man, sweating, beet-faced, posing stiffly with the stiff for press pictures. This was in the same room where, late last night, those thousands of “morbids” milling about the morgue had finally been allowed to file past their dead “hero.”

Then Walsh moved to the inquest room where the noon sun blazed through the wire mesh on the windows and made checkerboard patterns on the spectators and witnesses and officials who baked their way through the perfunctory proceedings.

“The odd thing,” Davis said, “is Melvin Purvis wasn’t there. By all accounts, it was his operation—some of the witnesses say he’s the one fired the shot—but instead his assistant Cowley takes the stand.”

I didn’t correct any of that, just nodded interestedly.

“And Cowley ducked the issue—when Walsh asked him who committed this ‘homicide,’ Cowley would only say that it was ‘a government agent, properly authorized.’ No names. And they never even broached the subject of who the informant was.”

“Is that right.”

“Do

you

know, Heller? Do you know who the ‘lady in red’ is? Or the other dame with Dillinger? What were you doing there, anyway?”

I sipped my milk; it was getting warm. “Did they introduce fingerprints into evidence?”

He shook his head. “Another government agent testified that the prints corresponded, is all. They didn’t enter comparisons of the prints or anything—this guy just said the prints compared. A botched acid job, I hear.”

Davis meant the corpse’s fingertips had been dipped in acid, back when he was alive, in the usual (unsuccessful) underworld attempt to obliterate prints.

“And,” he continued, “the pathologist, Kearns, read a summary of his autopsy. Four wounds, one of which caused death.” He got a notebook out of his back pocket and flipped through some pages; read aloud: “‘Medium developed white male, thirty-two years of age, five feet seven, one hundred and sixty pounds, eyes brown.’” He put the notebook away, shrugging again. “Pretty standard.”

“I see.”

He stirred his coffee absentmindedly. “Something else odd, though. The corpse only had seven dollars and eighty cents. Word was Dillinger always wore a money belt, with thousands of dollars. Think somebody stole it?”

“Maybe that money belt’s just a myth.”

“Yeah, maybe. But why would a guy like Dillinger, who might have to lam at any moment’s notice, go out with little more than movie and popcorn money?”

“I wouldn’t know.”

“And another thing—why the hell’d he go out without a coat?”

“It was hot.”

“Very funny, Heller. It’s hot today, too. But where’d he tuck his gun, if he didn’t have a coat to hide it under?”

“Good question.”

“Did you see he had a gun at the scene?”

“There was a gun in his hand, by the time he was dead.”

He thought that over. “It wasn’t entered into the coroner’s docket at the inquest, this gun Dillinger supposedly drew on Purvis.”

I smiled. “Since when is a gun turning up in a dead suspect’s hand news in Chicago?”

He sat forward and pointed at me like Uncle Sam. “Look, if you really know some inside dope, I can get you some

real

money. If you know the lady in red’s name, for instance…”

“I’ll give you my story for fifty bucks, but you got to mention my business by name and give the address.”

“Done.”

I sipped my milk. “That way Baby Face Nelson and Van Meter and the rest will know where to find me.”

He grinned, then the grin faded. “You think Johnny’s buddies might really seek revenge?”

“No. I think they got better things to do.”

“Such as?”

“Such as read the writing on the wall. Such as rob a few more banks before going south. Things are closing in on them. The feds may be stupid, but they can cross state lines and carry guns. The Wild West show will be closing down soon—after one last bloody act.”

“Can I quote you on that?”

“Do, and I’ll crucify you in Marshall Field’s window. That sort of talk just

might

tempt the likes of Nelson into retaliating.”

“I hear he’s a fruitcake.”

“Can I quote

you

on that?”

“Okay, okay. So what’s your story, Heller?”

I told him my story. I told him that in the course of working in Uptown on a divorce case for a client, who would have to remain nameless, I’d stumbled upon a man who resembled John Dillinger. I’d reported this to Melvin Purvis and Samuel Cowley of the federal Division of Investigation. They had kept me informed as the inquiry developed, including the fact that two East Chicago, Indiana, police officers had corroborated my story through their own sources. For that reason, I’d been invited as an observer to the showdown at the Biograph.

I also gave him a detailed description of the way the stakeout had been conducted, and the manner in which the suspect had been taken down, though I did not mention that he’d been shoved to the pavement and shot in the back of the head. I said only that officers had swarmed toward him and shots had been fired.

No mention of Anna Sage, Polly Hamilton or Jimmy Lawrence.

I sipped my milk.

Frank Nitti would’ve been proud of me.