Truman (49 page)

Authors: David McCullough

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Presidents & Heads of State, #Political, #Historical

Their present oppressors must know that they will be held directly accountable for their bloody deeds. To do all this, we must draw deeply on our traditions of aid to the oppressed, and on our great national generosity. This is not a Jewish problem, it is an American problem—and we must and we will face it squarely and honorably.

It was a remarkable speech, one of the strongest he ever made. How very important it was that he felt as he did, neither he nor any of his audience could possibly yet know.

With other senators on the committee—Hatch, Ball, Harold Burton—Truman was giving more and more thought to problems of the postwar world. And though he played no direct part in the drafting of a Senate resolution for the establishment of a postwar international organization, a United Nations—a resolution sponsored by Senators Ball, Burton, Hatch, and Lister Hill, and hence known as B

2

H

2

—Truman was the acknowledged guiding spirit. The United States could, “not possibly avoid the assumption of world leadership after this war,” he was quoted in

The New York Times.

And with Republican Congressman Walter Judd of Minnesota, who had also fought in World War I, Truman set out on a Midwest speaking tour in the summer of 1943 to spread the internationalist word under the sponsorship of the United Nations Association. He kept hammering at the same themes over and over across Iowa, Nebraska, Kansas, and Missouri. “History has bestowed on us a solemn responsibility…. We failed before to give a genuine peace—we dare not fail this time…. We must not repeat the blunders of the past.”

Not all the Truman Committee’s efforts were successful. The Canol Project went on and wound up costing $134 million, all money that need never have been spent, and more serious even than the financial waste was the misuse of vitally needed manpower and materials. (At one point 4,000 troops and 12,000 civilians were involved.) Corporations and government agencies found to be bungling things or committing outright fraud, like Carnegie-Illinois Steel, were frequently let off the hook to keep production rolling. “We want aluminum, not excuses,” Truman said after the committee’s tangle with Alcoa.

Yet overall the committee’s performance was outstanding. It would be called the most successful congressional investigative effort in American history. Later estimates were that the Truman Committee saved the country as much as $15 billion. This was almost certainly an exaggeration—no exact figure is possible—but the sum was enormous and unprecedented, and whatever the amount, it was only part of the service rendered. The most important “power” of the committee was its deterrent effect. Fear of investigation or public exposure by the committee was enough in itself to cause countless people in industry, government, and the military to do their jobs right, thereby, in the long run, saving thousands of lives.

It was not just that the production of defective airplane engines or low-grade steel had been exposed; the committee also made positive contributions to the production of improved military equipment. The most notable—and one that saved many lives—was the famous, hinge-prowed Higgins landing craft used for amphibious assault, which was built and ordered by the Navy’s Bureau of Ships only after heavy prodding from the committee. With the new Higgins craft troops could be landed on a variety of shallow beaches, rather than just established harbors. It increased mobility for the offense, made obsolete much of the old coastal defenses. Yet until the committee looked at the subject with a fresh eye, Navy bureaucrats had been trying to force the adoption of a plainly inferior design.

The committee was also a continuing source of information about the war effort for the whole country. In its report on the loss to U-boats, for example, the committee said 12 million tons of American shipping were destroyed in 1942, an alarming figure. This was 1 million tons more than all the nation’s shipyards were then producing. The Navy immediately denied the validity of the report. But when Secretary of the Navy Knox appeared before the committee in executive session, he admitted the committee was telling the truth.

Unquestionably, the relentless “watchdog” role, the attention to detail during the hearings, the quality as well as the quantity of the reports issued, all greatly increased public confidence in how the war was being run. Further, anyone called before the committee could count on a fair hearing. The chairman would have it no other way.

From what he had observed of Chairman Truman during the day of General Somervell’s testimony, Allen Drury of United Press recorded: “He seems to be a generally good man, probably deserving of his reputation.” But after watching several more sessions, including one in which Truman went out of his way to keep some of the other senators from browbeating a witness, Drury could hardly say enough for the head of the committee:

April 12, 1945: Harry S. Truman takes the oath of office from Chief Justice Harlan F. Stone in the Cabinet Room at the White House.

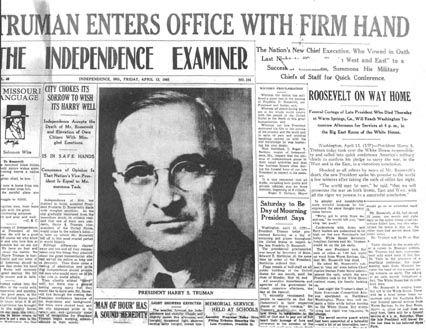

Expressions of grief, as well as confidence in Harry Truman, fill the front page of the Independence

Examiner

.

James F. Byrnes (left) and Henry A. Wallace, ardent candidates for the vice-presidential nomination only the summer before, wait with Truman for Roosevelt’s funeral train at Washington’s Union Station. Below: The new President of the United States at his desk.

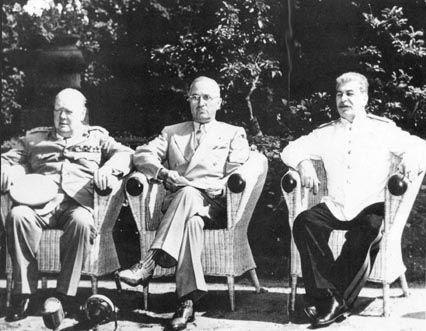

July 1945: Prime Minister Winston Churchill, President Truman, and Generalissimo Joseph Stalin, “The Big Three,” meet at Potsdam, Germany.

Conference table, Cecilienhof Palace.

Truman in Berlin with Generals Eisenhower and Patton. Eisenhower was high on the new President’s list of favorite generals; not so Patton.

Above: Truman’s headquarters during the Potsdam Conference was No. 2 Kaiserstrasse, the “nightmare” house where the decision on the atomic bomb was made. Below: Truman’s desk in the second-floor study.

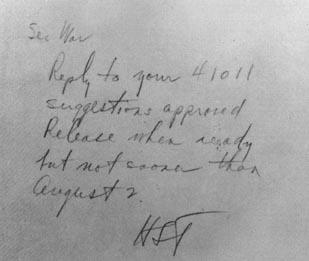

Above: Truman’s order, handwritten in pencil to Secretary of War Stimson, to use the atomic bomb on Japan. Below: At his desk in the Oval Office, 7:00

P.M.

, August 14, 1945, Truman announces the surrender of Japan.

May 25, 1946: As he calls on Congress for the power to draft striking rail workers into the Army and thus break a nationwide shutdown, Truman is handed a note saying the strike has ended. Left: He and the First Lady had hosted a reception for wounded veterans the day before, just as worries over the rail strike were at their worst. The postwar burdens of his office bore heavily on Truman (opposite). But he had discovered a retreat away from Washington, the naval base at Key West, Florida, and aide Clark Clifford (shown below with Truman at Key West) had emerged as a bright new star on the White House staff.