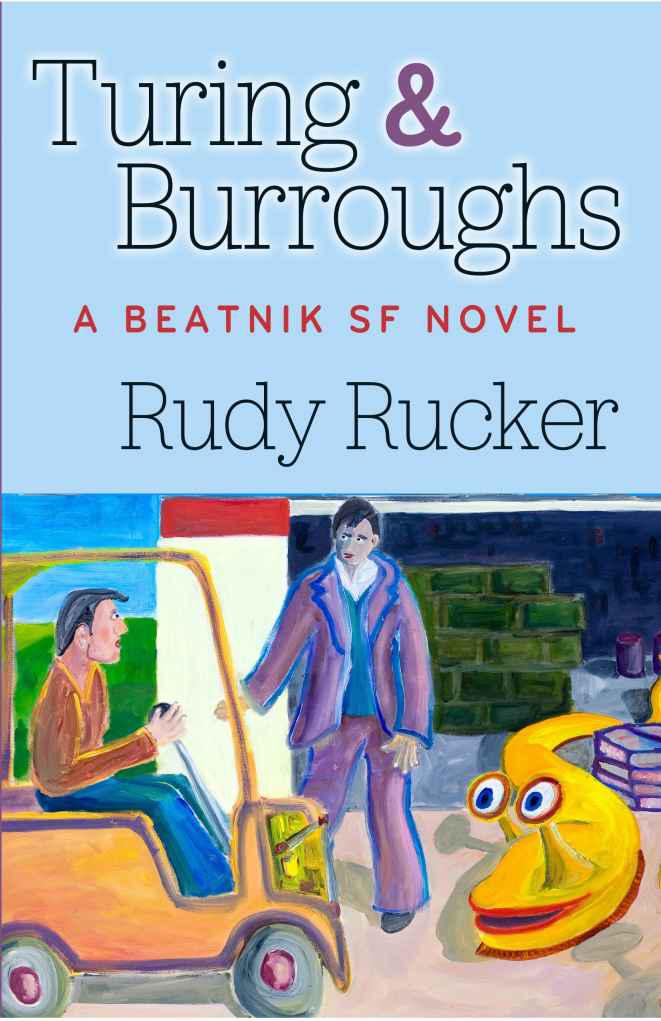

Turing & Burroughs: A Beatnik SF Novel

Read Turing & Burroughs: A Beatnik SF Novel Online

Authors: Rudy Rucker

Turing & Burroughs

A Beatnik SF Novel

Rudy Rucker

Transreal Books

www.transrealbooks.com

Turing & Burroughs:A Beatnik SF Novel

Copyright © 2012 by Rudy Rucker.

The first edition appeared in ebook and print in Fall, 2012.

The cover painting is

A Skugger’s Point of View

by Rudy Rucker.

The cover is by Georgia Rucker Design.

Print ISBN: 978-0-9858272-3-6

Ebook ISBN: 978-0-9858272-4-3

Transreal Books

Los Gatos, California

Acknowledgements

Four chapters of

Turing & Burroughs

appeared as stories: “The Imitation Game” in

Interzone

#2, 2008; “Tangier Routines” in

Flurb

#5, 2008; “The Skug” in

Flurb

#10, 2010; and “Dispatches From Interzone” in

Flurb

#11, 2011. “The Imitation Game” also appeared in

The Mammoth Book of Alternate Histories

, edited by Ian Watson and Ian Whates (Robinson, London 2010).

The description of Alan Turing at the Sunset Lounge in West Palm Beach is adapted from a scene in

Bird Lives: The Life of Charlie Parker

, by Ross Russell (Charterhouse 1973).

The passage about the Happy Cloak that my Burroughs character quotes is indeed from

Fury

, a novel by Henry Kuttner and his wife C. L. Moore. That novel first appeared as a 1947 serial in the

Astounding

science fiction magazine, and has been republished in numerous editions, including a 1950 Grosset & Dunlap hardback under Kuttner’s name alone, and as a 2010 ebook from Rosetta Books.

My chapters in the form of letters are heavily influenced by the collected letters of William Burroughs, see

Letters to Allen Ginsberg

1953-1957, (Full Court Press, New York 1982) and

The Letters of William Burroughs

1945-1959, edited by Oliver Harris, (Viking, New York, 1993).

My chapter “The Apocalypse According to Willy Lee” draws not only on Burroughs’s letters but on his novels

The Western Lands

and Q

ueer

. And my final chapter, “Last Words” is inspired by Burroughs’s books

The Yage Letters

and

Last Words

.

Thanks to these readers for their help with proofreading and copy editing: Roy Whelden, Alex McLaren, Jon Pearce, Arthur Hlavaty, John Walker, and Sylvia Rucker.

Chapter 1: The Imitation Game

It was a rainy Sunday night, June 6, 1954. Alan Turing was walking down a liquidly lamp-lit street to the Manchester railway station, wearing a long raincoat with a furled umbrella concealed beneath. His Greek paramour Zeno was due on the 9 p. m. train, having taken a ferry from Calais. And, no, the name had no philosophical import, it was simply the boy’s given name—although it was indeed the case that at times dear Zeno could protract a seemingly finite interval of time into an endless sum of ever-subtler pleasures. Not that he’d think of it that way.

If all went well, Zeno and Alan would be spending the night together in the sepulchral Manchester Midland travelers’ hotel—Alan’s own home nearby was watched. He’d booked the hotel room under a pseudonym.

Barring any intrusions from the morals squad, Alan and Zeno would set off bright and early tomorrow for a lovely week of tramping across the hills of the Lake District, free as rabbits, sleeping in serendipitous inns. Alan sent up a fervent prayer, if not to God, then to the deterministic universe’s initial boundary condition.

“Let it be so.”

Surely the cosmos bore no distinct animus towards homosexuals, and the world might yet grant some peace to the tormented, fretful gnat labeled Alan Turing. But it was by no means a given that the assignation with Zeno would click. Last spring, the suspicious authorities had deported Alan’s Norwegian flame Kjell straight back to Bergen before Alan even saw him.

It was as if Alan’s persecutors supposed him likely to be teaching his men top-secret code-breaking algorithms, rather than sensually savoring his rare hours of private joy. Although, yes, Alan did relish playing the tutor, and it was in fact conceivable that he might feel the urge to discuss those topics upon which he’d worked during the war years. After all, it was no one but he, Alan Turing, who’d been the brains of the British cryptography team at Bletchley Park, cracking the Nazi Enigma code and shortening the War by several years—little thanks that he’d ever gotten for that.

The churning of a human mind is unpredictable, as is the anatomy of the human heart. Alan’s work on universal machines and computational morphogenesis had convinced him that the world is both deterministic

and

overflowing with endless surprise. His proof of the unsolvability of the Halting Problem had established, at least to Alan’s satisfaction, that there could never be any shortcuts for predicting the figures of Nature’s stately dance.

Few but Alan had as yet grasped the new order. The prating philosophers still supposed, for instance, that there must be some element of randomness at play in order that each human face be slightly different. Far from it. The differences were simply the computation-amplified results of disparities among the embryos and their wombs—with these disparities stemming in turn from the cosmic computation’s orderly growth from the universe’s initial conditions.

Of late Alan had been testing his ideas with experiments involving the massed cellular computations by which a living organism transforms egg to embryo to adult. Input acorn—output oak. He’d already published his results involving the dappling of a brindle cow, but his latest experiments were so close to magic that he was holding them secret, wanting to refine the work in the alchemical privacy of his starkly under-furnished home. Should all go well, a Nobel prize might grace the burgeoning field of computational morphogenesis. This time Alan didn’t want a droning gas-bag like Alonzo Church to steal his thunder—as had happened with the Hilbert

Entscheidungsproblem

.

Alan glanced at his watch. Only three minutes till the train arrived. His heart was pounding. Soon he’d be committing lewd and lascivious acts (luscious phrase) with a man in England. To avoid a stint in jail, he’d sworn to abjure this practice—but he’d found wiggle room for his conscience. Given that Zeno was a visiting Greek national, he wasn’t, strictly speaking, a “man in England,” assuming that “in” was construed to mean “who is a member citizen of.” Chop the logic and let the tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil fall, soundless in the moldering woods.

It had been nearly a year since Alan had enjoyed manly love—last summer on the island of Corfu with none other than Zeno, who’d taken Alan for a memorable row in his dory, a series of golden instants fused into a lambent flow. Alan had just been coming off his court-ordered estrogen treatments, but that hadn’t mattered. In Alan’s case the hormones had in fact produced no perceptible reduction in his libido. The brain, after all, was the most sensitive sex organ of them all. By now he’d suffered a year’s drought, and he was randy as a hat rack. He felt as if his whole being were on the surface of his skin.

Approaching the train station, he glanced back over his shoulder—reluctantly playing the socially assigned role of furtive perv—and sure enough, a weedy whey-faced fellow was mooching along half a block behind, a man with a little round mouth like a lamprey eel’s. Officer Harold Jenkins. Devil take the beastly prig!

Alan twitched his eyes forward again, pretending not to have seen the detective. What with the growing trans-Atlantic hysteria over homosexuals and atomic secrets, the security minders grew ever more officious. In these darkening times, Alan sometimes mused that the United States had been colonized by the lowest dregs of British society: sexually obsessed zealots, degenerate criminals, and murderous slave masters.

On the elevated tracks, Zeno’s train was pulling in. What to do? Surely Detective Jenkins didn’t realize that Alan was meeting this particular train. Alan’s incoming mail was vetted by the censors—he estimated that by now Her Majesty was employing the equivalent of two point seven workers full time to torment that disgraced boffin, Professor A. M. Turing. But—score one for Prof. Turing—his written communications with Zeno had been encrypted via a sheaf of one-time pads he’d left in Corfu with his golden-eyed Greek god, bringing a matching sheaf home. Alan had made the pads from clipped-out sections of identical newspapers; he’d also built Zeno a cardboard cipher wheel to simplify the look-ups.

No, no, in all likelihood, Jenkins was in this seedy district on a routine patrol, although now, having spotted Turing, he would of course dog his steps. The arches beneath the elevated tracks were the precise spot where, two years ago, Alan had connected with a sweet-faced boy whose dishonesty had led to Alan’s conviction for acts of gross indecency. Alan’s arrest had been to some extent his own doing; he’d been foolish enough to call the police when one of the boy’s friends burglarized his house. “Silly ass,” Alan’s big brother had said. Remembering the phrase made Alan wince and snicker. A silly ass in a dunce’s cap, with donkey ears. A suffering human being nonetheless.

The train screeched to stop, puffing out steam. The doors of the carriages slammed open. Alan would have loved to sashay up there like Snow White on the palace steps. But how to shed Jenkins?

Not to worry; he’d prepared a plan. He darted into the men’s public lavatory, inwardly chuckling at the vile, voyeuristic thrill that disk-mouthed Jenkins must feel to see his quarry going to earth. The echoing stony chamber was redolent with the rich scent of putrefying urine, the airborne biochemical signature of an immortal colony of microorganisms indigenous to the standing waters of the train station pissoir. It put Alan in mind of his latest Petri-dish experiments at home.

Capitalizing on his newly formulated theory of morphonic fields, he’d learned to grow stripes, spots, and spirals in the flat mediums, and then he’d moved into the third dimension. He’d grown lumps, tendrils, and, just yesterday, a congelation of tissue very like a human ear.

Like a thieves’ treasure cave, the train-station bathroom had a second exit—over on the other side of the elevated track. Striding through the loo’s length, Alan drew out his umbrella, folded his mackintosh into a small bundle tucked beneath one arm, and hiked up the over-long pants of his dark suit to display the prominent red tartan spats that he’d worn, the spats a joking gift from a Cambridge friend. Exiting the jakes on the other side of the tracks, Alan opened his high-domed umbrella and pulled it low over his head. With the spats and dark suit replacing the beige mac and ground-dragging cuffs, he looked quite the different man from before.

Not risking a backward glance, he clattered up the stairs to the platform. And there was Zeno, his handsome, bearded face alight. Zeno was tall for a Greek, with much the same build as Alan’s. As planned, Alan paused briefly by Zeno as if asking a question, privily passing him a little map and a key to their room at the Midland Hotel. And then Alan was off down the street, singing in the rain, leading the way.