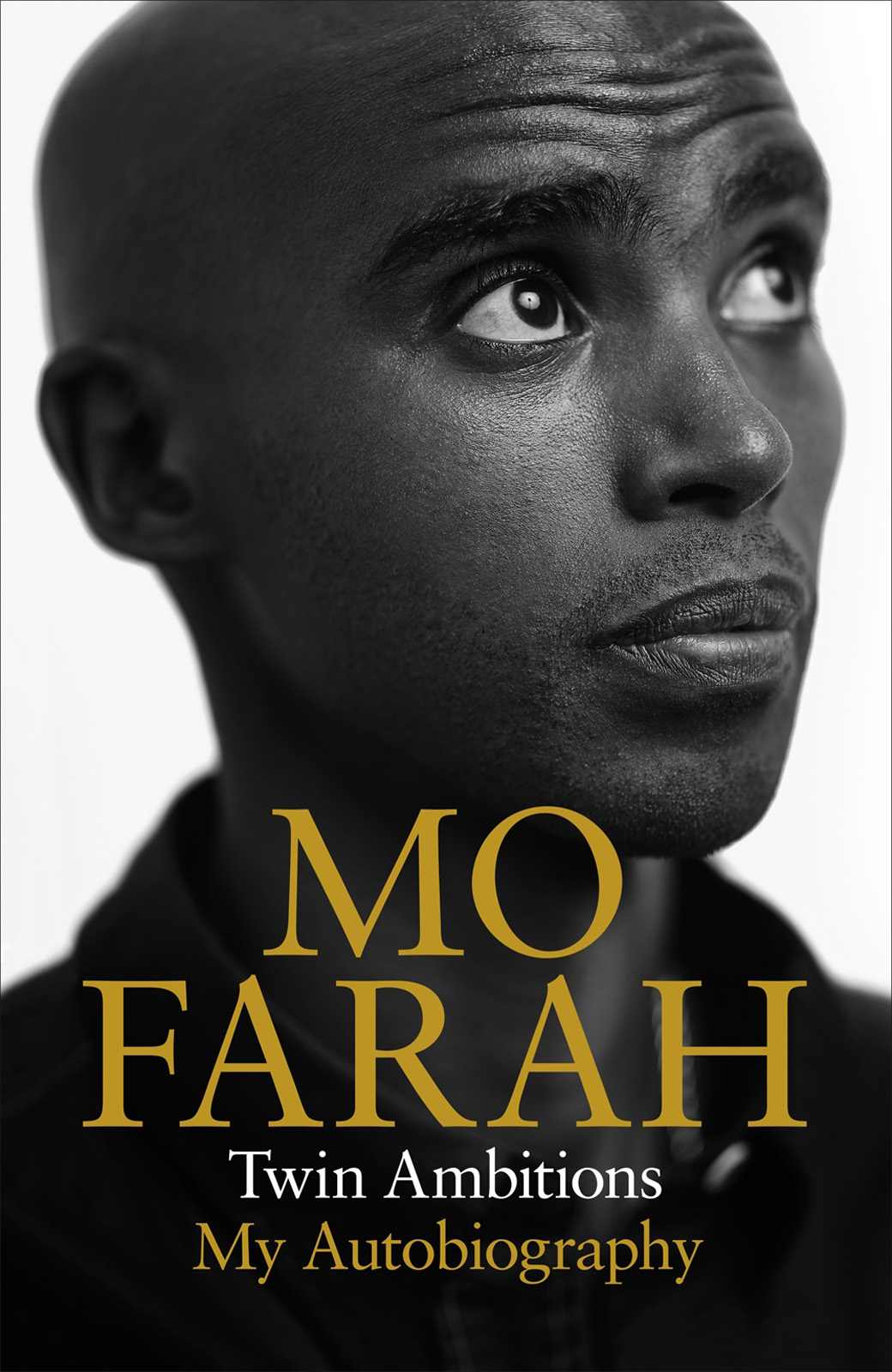

Twin Ambitions - My Autobiography

Read Twin Ambitions - My Autobiography Online

Authors: Mo Farah

MO FARAH was born in Mogadishu, Somalia in 1983. As a young child he spent time in Djibouti before moving to England at the age of eight. Mo initially struggled with the language barrier, but his PE teacher at Feltham Community College, Alan Watkinson, quickly spotted his potential as a runner and encouraged him to join Borough of Hounslow Athletics Club. After attending St Mary’s Endurance Performance and Coaching Centre in Twickenham, Mo became a professional athlete. At the 2012 London Olympic Games he won gold in the 10,000m – Britain’s first gold in this event. He followed this up with a stunning victory in the 5000m to become, in the words of Dave Moorcroft, ‘the greatest male distance runner that Britain has ever seen.’ Mo was appointed CBE in the Honours List in 2013. He lives in Portland, Oregon with his wife Tania, and their three daughters Rhianna, Aisha and Amani.

My Autobiography

Mo Farah

with T. J. Andrews

First published in Great Britain in 2013 by Hodder & Stoughton

An Hachette UK company

Copyright © Mo Farah 2013

The right of Mo Farah to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781444779592

Hodder & Stoughton Ltd

338 Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

For Rhianna, Aisha and Amani

CONTENTS

Prologue: The Loudest Noise in the World

16. Only the Ending is Different

T

HERE

are so many people I wish to thank. My beautiful daughters, Rhianna, Aisha and Amani, and my wife Tania: you mean the world to me. I am forever grateful for the love of my family: my twin brother, Hassan, my mum Aisha and my dad Muktar, my brothers Ahmed, Wahib and Mahad, my aunt Kinsi and my cousin Mahad.

I’d also like to thank Alan Watkinson, my old PE teacher at school and the guy who made it all happen for me. My thanks to my coaches down the years: Alex McGee, Conrad Milton, Alan Storey and Alberto Salazar. Success is never down to any one person. Every coach I’ve worked with has played their part in everything I’ve achieved. Without them, I might not have gone as far as I have done.

Thanks must go to my support team: my agent Ricky Simms and Marion Steininger at PACE; Neil Black, my physio; and Barry Fudge, my doctor, for all their support and helping me along the way. My in-laws, Bob and Nadia, who helped out with the girls when my career kept me away from my family.

Thanks also to my publisher, Roddy Bloomfield, editor Kate Miles and the rest of the team at Hodder & Stoughton for helping me to put my story on the page.

Finally, my thanks to Allah, for putting me on this Earth, and for giving me the talent to run.

THE LOUDEST NOISE IN THE WORLD

11 August 2012. 7.41 p.m. Olympic Stadium, London.

T

HREE

laps to go in the final of the 5000 metres, on a warm summer’s evening in Stratford, east London, and I am 180 seconds from history.

I’ve been here before. Seven days ago, in fact, on Super Saturday, when first Jessica Ennis, then Greg Rutherford and then me won three Olympic gold medals in less than an hour, adding to the two golds won earlier in the day by the rowing team at Eton Dorney and the women’s pursuit team at the velodrome. The feeling is different now. Going into the 10,000 metres final I had so much pressure on me it felt like I was lugging around two big bags of sugar over my shoulders. People were desperate for me to win that race. When I crossed that white line as the winner, this immediate sense of relief washed over me. Now the pressure is off. I’m running free. I have one gold medal in the bag. Whatever happens out here tonight, I’m an Olympic champion. No one can take that away from me.

Don’t get me wrong. I still want to win – more than anything. But this time I’m able to go out there and race and actually enjoy it: the competition, the stadium, the occasion. And the crowd. The pulsating, deafening roar of the British fans.

I’m in second place. Ahead of me is Dejen Gebremeskel, the Ethiopian runner. At the start of the race I’d figured he was one of my main threats going onto the home straight. But Gebremeskel has kicked on early, moving out to the front and pushing the pace. Big surprise. But for me, that’s perfect. He’s gone early for a good reason: he thinks that I must still be feeling the effects of the 10,000 metres in my legs. Figures I must be tired. That if he pushes the pace quite early on, he can wear me out on the last couple of laps, taking me out of the equation when it comes down to the sprint finish. If I was in Gebremeskel’s shoes, I’d be thinking the same thing. I’ve done more running than anyone else in the field, with the exception of the Ugandan, Moses Kipsiro, and my training partner, Galen Rupp. But Gebremeskel hasn’t taken into account my secret weapon: the crowd.

Everyone is roaring me on. The noise is unbelievable. Like nothing I’ve ever heard before. The crowd is giving me a massive boost. I think about how many people are crammed inside the stadium – how many millions more are watching on TV at home, cheering me on. Willing me to win. None of the other guys out there on the track are getting this kind of support. Everyone is rooting for me. The noise gets louder and louder. The crowd is lifting me. Pushing me on through the pain, towards the finish line.

Every athlete has five gears. That night, in the cauldron of the Olympic Stadium, I like to think the crowd gave me a sixth gear. They played a huge part in what I went on to achieve.

With two laps to go, I pull clear of Gebremeskel. The crowd goes ballistic. I’m getting closer, closer, closer to the line. The crowd is getting louder, louder, louder. Then I hit the bell. I’m still in the lead. One of the other guys tries to surge ahead of me. I hold him off. As I go round the track on that last lap, the entire crowd rises to its feet, section by section. It’s almost like a Mexican wave is chasing me around the stadium. I will never feel something like that again in my entire life. I can’t describe how loud it is. Without a doubt, it’s the loudest noise I have ever heard in my life. The crowd physically lifts me towards the finish. I remember Cathy Freeman describing the atmosphere at the 400 metres final in Sydney in 2000, the euphoria of the crowd almost carrying her across the line. As I head down that home straight in the lead, I start to understand what she meant.

Two hundred metres to go now. I’m still out in front. Somehow the crowd is growing even louder. Gebremeskel tries it on going into the home straight but I hold him off and cross the finish line in first place.

For a few moments I can’t believe what has happened. ‘Oh my God,’ I think. ‘Oh my God, I’ve done it.’ I keep repeating it to myself, over and over: ‘I’ve done it. I’ve won.’ All around me the crowd is going wild. Suddenly it hits me: I am a double Olympic champion. I have gone where no British distance runner has gone before.

I sink to my knees. The roar of the crowd booming in my ears. Getting here has taken a lot of hard work and sacrifices. I’ve had to come a long, long way and go through so many highs and lows. Looking back, it’s been an amazing journey.

TWIN BEGINNINGS

P

EOPLE

often ask me what it’s like to have a twin brother. I tell them: there’s this special connection that the two of you have. Like an intuition. You instinctively feel what the other person is going through – even if you live thousands of miles apart, like Hassan and me. It’s hard to explain to someone who doesn’t have a twin, but whenever Hassan is upset, or not feeling well, I’ll somehow sense it. The same is true for Hassan when it comes to sensing how I feel. He’ll just know when something isn’t right with me. Then he’ll pick up the phone and call me, ask how I am. Or I’ll call him. From the moment we were born, on 23 March 1983, we were best friends.

We come from solid farming stock. My family has always been based in the north of the country, going back generations. My great-great-grandparents on my dad’s side were farmers in a remote village called Gogesa, in the Woqooyi Galbeed region of northwest Somalia, not far from the border with Ethiopia. It’s a rural area with fertile land, so farming is the main occupation for the local people, and if you drive through Gogesa, you’ll see farms and open countryside full of grazing animals. My great-great-grandparents owned cows and sheep and camels and farmed the land. After they died, my great-grandfather, Farah, inherited the farm. He was well known locally because part of the farmland he owned contained a natural spring that pumped fresh water to the surface. Water was scarce in the region at the time, and soon many locals were collecting water from the spring. My great-grandfather was the guy with the water.

His daughter, Amina, my

ayeeyo

(grandma) on my dad’s side of the family, spent time in Djibouti as a young woman. Djibouti is a tiny country that shares borders with Eritrea, Ethiopia and Somalia. To the north you’ve got the Red Sea, and on the other side of the water is the Arabian peninsula, with Yemen, Oman and Saudi Arabia. A number of people from places like Gogesa made the same journey across the border as Grandma Amina. As a former French colony, Djibouti offered better prospects than an agricultural village. There were more jobs in Djibouti City, better education, and a higher standard of living. Even as a kid, I remember having this idea of Djibouti as a place where people wore nice clothes and earned good salaries. For much of the year, my grandma lived and worked in Djibouti City. When Djibouti got too hot in the summer, Grandma would travel back to Gogesa for the holidays. The details are a bit sketchy – this is all such a long time ago – but I believe that when my great-grandfather died, the farm was sold up and my grandma moved permanently to Djibouti. They pretty much settled there. Grandma was still living in Djibouti with my grandad, Jama, by the time I was born.

My parents met while my dad was on a trip back to Somalia from the UK, where he was studying and working. They later settled down to married life and shortly after, me and Hassan were born. Hassan came out first. Twenty-nine years later, my wife Tania also gave birth to twin girls. Hassan even married a twin. You could say that twins are in our blood. My brother was named Hassan Muktar Jama Farah. I took on the name Mohamed Muktar Jama Farah.

I should explain something about our names. Everyone in Somalia belongs to a clan. Our clan was the Isaaq, the biggest clan in the north of the country. Your family name and your clan are linked together as a way of identifying not only who you are, but where you come from and what clan you belong to. Take my name. Mohamed is my given name. After your first name comes your father’s first name (Muktar). Third is your grandfather’s first name (Jama). The fourth part of your name is your great-grandfather’s name (Farah). If someone stopped me in the street and asked, ‘What’s your name?’ I would tell them, ‘Mohamed Muktar Jama Farah, nice to meet you.’ And then they would say, ‘Ah, I used to know your grandad, Jama! I remember your dad, Muktar, as a little boy!’ Usually it was the oldest guy in the village asking the questions. They could trace my ancestry that far back, they’d know what clan I belonged to and the names of distant relatives.