Twisted (16 page)

Authors: Jay Bonansinga

“What thing?”

He took another huge, hungry pull off the bottle. “The thing that lives in the wind, the one that's killing people. The same thing that got Moses.” The matter-of-fact tone of his voice made the skin tighten on the back of Maura's neck. Michael looked up at her. “Oh ... I know what you're thinking, you're thinking this kid is nuts, right? A couple of sandwiches short of a picnic? Elevator don't go all the way to the top? All those colorful euphemisms for bug-fuck loony?”

“Michael, I didn't sayâ”

“It's okay. I don't blame ya.” He took another gulp. Another shudder, hands still trembling uncontrollably. “I don't know what it is ... man, monster, rabid alligator. I don't know. But there's

something

there.” He looked at her again. “In the hurricanes ... y'all know it as well as I do. I can tell by the look on your face.”

something

there.” He looked at her again. “In the hurricanes ... y'all know it as well as I do. I can tell by the look on your face.”

A gust rattled the front shutters, and made Michael jump. He took another sip and closed his eyes, trying to breathe as deeply as possible. A tear tracked down his brown cheek. He reminded Maura of a shell-shocked GI still hearing the distant thrum of the battlefield.

“I gotta get goin',” he said at last, “get outta here before she hits.”

“Michael, um ... there's something I should tell you. It's about why I'm here.”

The young man looked up at her. His eyes were wet with terror, his lips still quivering.

Maura told him all about her relationship with Ulysses Grove, and her work for

Discover

magazine. But most importantly, she told him that she was now assisting Grove in an investigation of the hurricane murders. That's how she came to read De Lourde's journals. But she could not make much sense of them. So now, obviously, anything that Doerr might be able to tell her about the Yucatan, or the significance of the hurricane that hit down there, or just exactly what this “thing” that lived in the wind was, or

anything

else, would be very helpful.

Discover

magazine. But most importantly, she told him that she was now assisting Grove in an investigation of the hurricane murders. That's how she came to read De Lourde's journals. But she could not make much sense of them. So now, obviously, anything that Doerr might be able to tell her about the Yucatan, or the significance of the hurricane that hit down there, or just exactly what this “thing” that lived in the wind was, or

anything

else, would be very helpful.

When Maura finished, Doerr looked up at her and said, “You knew that Moses and I were partners, boyfriends. . . right?”

She told him she knew.

“He was a unique person.” Doerr chewed his lip to stifle the pain and grief creeping up on him. More tears welled up in his eyes. “He taught me so much. He was a pioneer in the field, did you know that? They laughed at him when he made his presentation to the Royal Academy. That was in the fall, after he came back. They

laughed

at him. Pompous asses.”

laughed

at him. Pompous asses.”

He shuddered again at the muffled sound of the wind whistling across the tile roof.

Maura sat down beside him on the couch, patted his shoulder, and said, “What happened to you down there in the Yucatan? In his journals, Moses said you ran away.”

He looked down into his lap, wringing his hands. Maura noticed his nails had been chewed down to the quick. “I didn't sign up for hurricanes, okay?” His voice was strangled with shame. “I was traveling as a teaching assistant, and a companion, and I wanted to learn about the Toltecs, but I never dreamed that we wouldâ” He bit off the thought, driving it out of this memory. “I basically, like, freaked out.” He looked up at her. “Basically I panicked. Okay? I'm not proud of it, but when the hurricane hit I just lost it. I bailed, and hid in the back of a supply van, then rode it back down the mountain, back into Merida. I left the next morning. Soon as I got home, I dropped out. Totally just quit. Been trying to figure out what to do with myself ever since then. Can't sleep, been drinking myself into blackouts.” He looked up at her. “But Moses knew what was going on all along. They laughed at him. Now look what's happening.”

An anguished pause. Maura watched him. “You're referring to the murders, right? The âthing' in the eye of the storm?”

Doerr took another gulp of whiskey, then stood up and began pacing nervously across the tiny living room, his eyes shifting across the memories. “Moses believed that the true nature of these Toltec blood sacrificesâthe ones we discovered in the fossil recordâhad to do with

hurricanes

. He believed that there were these âhurricane cults' that performed human sacrifices in the eyes of storms to appease the angry nature gods.”

hurricanes

. He believed that there were these âhurricane cults' that performed human sacrifices in the eyes of storms to appease the angry nature gods.”

After a doom-laden pause Maura asked if De Lourde went to the Yucatan to prove this theory.

Doerr looked around the room like a caged animal. “I don't know, I don't know, that whole week is just a blur to me now.” Another big gulp of whiskey. He was starting to get woozy, softening his vowels a little. “But I'll tell you this much, the part that got everybody all riled up in the academic community was the part about the present-day cult.”

“What do you mean?”

“Moses believed there were members of this cult still active today. He believed that people were still getting sacrificed in the eyes of hurricanes.” He paused, wiping his eyes and his face. “Which makes his murder all the more horrible, don't you think? It's like some kind of cruel joke. Like he had to die just to prove his theory.”

Another pause.

Maura looked into Doerr's watery eyes. “What happened down there, Michael?”

He looked at her. “What do you mean?”

She asked what it was that had scared him so badly down there.

He swallowed back his tears. “You don't want to know.”

Maura stood up, went over to him, and gave his shoulder a tender pat. “It's okay. You can tell me.”

He started to silently cry again, and slowly knelt down to the floor as though his body were deflating. Tears beaded on his chin. He put his face in his hands. Then he looked up at her through his tears. “We found a mummy, a child ... just a little child,” he moaned in a strangled voice.

Maura knelt down beside him, put an arm around him, and stared at him, as Michael Doerr slowly, softly recounted the events of March 17, 2004... .

Â

Outside on the edge of the cliff, in the rain and the darkness, the sky opening up above him, Michael just stands there, getting soaked, while the others rush for cover, and the lightning stitches across the heavens above him, smelling of ozone and seawater, and he realizes he's going to die if he doesn't run for shelter.

The hurricane slams into the east range below him, sounding like a volley of cannon fire, and he can barely hear Professor De Lourde down there, staggering through the rain a hundred feet below him, with a lantern, screaming: “Michael! Michael, where are you!”

He looks down into the chasm below him, the excavation site barely visible in the blankets of rain. Carved out of the side of the rock face fifty feet down, jutting out on a shelf of sandstone, the site is bordered by rope cordons and marker sticks driven into cracks. It looks like a giant bite taken out of the side of the mountain.

In the shadows of the dig, the tarp covering the find suddenly tears away.

The canvas billows up, peels, and furls into the agitated air, revealing the mummy beneath it. The little delicate brown boy is curled into the fetal position, still partially buried in the sediment like a nesting doll. It looks so sad and lovely lying there in its dusty stasis. So well preserved its hair and eyes are still intact. Soon the turbulent rain finds the mummy. Overhead, the squall rises and mbles and turns into an angry whirlwind.

The wind knocks Michael down. Gasping for breath, he crawls out to the edge of the precipice. De Lourde has vanished now, taken cover with the rest of them, his shouts swallowed by the noise. The hurricane's eye wall is approaching off the coast now like a mad circus coming to townâthe whetstone scream of the inner winds rising and risingâand Michael has to hold on to an alpine root, a little knob of petrified wood, in order to maintain his clinging hold on the cliff's edge. He peers out over the cropping and gazes down at the mummified boy.

“He probably dates back to AD 900âa perfect example of Toltec child sacrificeâpoor little angel,” De Lourde's voice whispers and echoes in the back chambers of Michael's scrambled memory. Michael has been close to a full-blown breakdown since he arrived here in the Yucatan, barely functioning on an overdose of lithium and Xanax. And now the mummy has opened the secret wound inside him like a black lance through his heart.

“Just look at him. The sheer terror on his little face. The Incas supposedly sacrificed their best and brightest children, but they did it very infrequently, only in the direst of circumstances. And the fossil record shows us they did it humanelyâor at least

quickly

. The Toltecs were another story. They buried their children alive to appease some vague, obscure demigod. Amazing the pain and suffering religion has wrought on the world ... wouldn't you say, Michael?”

quickly

. The Toltecs were another story. They buried their children alive to appease some vague, obscure demigod. Amazing the pain and suffering religion has wrought on the world ... wouldn't you say, Michael?”

The wind suddenly buffets the precipice, the rain slashing Doerr like cutlasses across his exposed flesh, across his face and his arms. He tries to rise to his feet, tries to run, but another gale knocks him back down. He hears a terrible noise then, an unearthly booming noise from above. He manages to twist around and look up at the night sky.

Something is changing in the black whirlpool above him, a vast hole opening up in the sky. It looks like a great bloody wound gaping open in the dark clouds. And the sound that comes out of it is the worst sound Michael Doerr has ever heard, a sound that begins as an otherworldly vibration, a deep growl, as massive and powerful as an earthquake, but rising up into a monstrous, inhuman voice.

A voice from Michael's past.

Â

Â

“It was my dad's voice,” Michael Doerr mewled softly, gasping for air between racking sobs. He was on the floor of his bungalow now, his knees gathered up against his chest. He was hugging himself as though he might fall apart at any minute. “I mean, it was just the wind, I know that now, but it spoke to me in my dad's voice, and it all came back to me.”

A tortured pause.

Maura spoke softly. “It's okay, Michael, I mean, you don't have to go any further if you don't want to.”

He wiped snot from his face. “Up until then, I had blocked it all out of my mind. You see, I was raised by my mom and my stepdad, and I guess I just stuffed those memories of my biological dad so far down I didn't even know I had them.”

“Michael, you don't have toâ”

“He used to take me to this place, he called it the whipping post, seriously, he called it that.” Doerr cringed at the memory, the physical repulsion contorting his beautiful brown face into a mask of torment and hatred. “This little beat-up shed in the woods. He'd beat the shit outta me. Sometimes he'd do more than that. Sometimes he'd have his cronies join in, and they'd take turns with me.”

“Michaelâ”

“I pushed all those memories so far down, it was like they didn't exist, but then, when I saw that poor little child down there, that mummy, and what they'd done to it, the sacrifice, I felt like I was ...” He winced suddenly, the tears oozing down his face, dripping off his chin, his trembling chin. He looked like a broken rag doll. Limp, drained, battered, he tried to sit up and catch his breath. “I really need to get out of here, I'm sorry, I need toâ”

Outside the front windows, a zephyr of wind had risen suddenly.

Then several things happened all at once, taking Maura by surprise. The wind roared and slapped at the house like a watery cat-o'-nine-tails, whipping the shutters and lashing the roof tiles. At that precise same moment, another chorus of civil defense sirens erupted somewhere close by, the closest clarion call yet, and the two sounds blended like a dissonant symphony punctuating the tension in the room with a sharp, percussive whine. It almost sounded like a gargantuan animal shrieking in pain, and it instantly stiffened Maura's spine, and made her jerk toward the windows.

But at the same time she was aware of something else, out of the corner of her eye, happening almost simultaneously with the noise of sirens and wind: Michael Doerr had started wincing uncontrollably, wincing and cringing. She looked at him. For one wild moment Maura wondered again if Doerr had Tourette's syndrome or some other kind of neurological malady. “Michael? You all right?”

His face had seized up suddenly, twitching with tics and tremors, his eyes fluttering spastically as the storm announced itself outside. His eyes went white. Then he jerked backward, tripping over an ottoman and sprawling to the floor. Something resembling speech yawped out of him, and then he went rigid.

“Michael!”

Maura went over to him, knelt down, and touched his shoulder. His damp, feverish body felt like an engine vibrating. He lay supine on his back, shuddering, tremblers twitching through his nervous system, stiffening his joints, turning his fingers into claws, his hands involuntarily clenching and unclenching.

He was going into seizures.

13

As they raced along the rain-drenched interstate, Kaminsky and Grove weighed their options. Grove wanted to get to New Orleans as soon as humanly possible. He was worried about Maura, and he was concerned that they would not reach the Crescent City before the storm hit. He didn't want to get pinned down somewhere outside of town, and miss the arrival of the eye. The whole point was to catch the eye as it passed over the most populated area, giving Grove his best shot at meeting the killer.

Puffing his nasty cheroot, weaving through traffic, the Russian explained that all this could be academic. New Orleans might not even

exist

by the time they get there. He also reminded Grove that it would be next to impossible to track a killer in the middle of a hurricane's eye. Firstly, there was no guarantee that the eye would pass over the center of town, or anywhere close to a “trackable” area. Secondly, if it did, Grove would still be too petrified of running into the inner eye wall to “track” anybody. Thirdly, it would be very difficult to predict an eye's behavior, no matter how vast and calm it might seem. Kaminsky had witnessed eyes abruptly contracting into nothing with such ferocious suddenness they appeared to have never existed. To think that a manhunt could go down in the middle of an eye struck Kaminsky as the height of lunacy.

exist

by the time they get there. He also reminded Grove that it would be next to impossible to track a killer in the middle of a hurricane's eye. Firstly, there was no guarantee that the eye would pass over the center of town, or anywhere close to a “trackable” area. Secondly, if it did, Grove would still be too petrified of running into the inner eye wall to “track” anybody. Thirdly, it would be very difficult to predict an eye's behavior, no matter how vast and calm it might seem. Kaminsky had witnessed eyes abruptly contracting into nothing with such ferocious suddenness they appeared to have never existed. To think that a manhunt could go down in the middle of an eye struck Kaminsky as the height of lunacy.

“It's not a manhunt,” Grove said after a long, pregnant pause. He was gazing out the rain-streaked side window at the flow of traffic moving in the opposite direction, clogging the northbound lanes of the interstate like rats fleeing a sinking ship. About the only other vehicles now occupying the southbound lanes alongside Kaminsky's tricked-out Jeep were military vehicles.

“What do you mean it is not a manhunt? What are we risking our lives for down there?”

Grove looked at him. “I told you, Kay, you don't have to do this, you can bail out at any time.”

“What are we doing there if we are not hunting a man?”

Grove thought about it for a moment. “It's more like a fishing expedition.”

“A fishing what?”

“A fishing expedition, you know, you got your hook, your bait. You try and catch a fish. That's what we're going to be doing in the eyeâ

fishing.

”

fishing.

”

Kaminsky chewed his soggy cheroot for a moment, thinking it over. For the last fifty miles or so, the Russian had refrained from lighting the cigar at Grove's behest. The smoke had gotten to the profiler, and he had begged his old friend to lighten up on the stogies. Now the Russian chewed the cheroot and pondered the steel-gray southern horizon.

They were making good time, despite the horizontal rain hammering them, intensifying with each passing mile. There was less southbound traffic than Kaminsky had expected, and the Jeep was holding up fairly well. At this rate, if they limited their restroom stops and ate on the road, they might even make New Orleans by six o'clock. That is, if Fiona didn't quicken her pace ... and if the roadblocks didn't pin them out ... and if the Louisiana roads didn't flood out on them.

If ... if ... if ...

that was a lot of

if

s.

If ... if ... if ...

that was a lot of

if

s.

Finally the big man turned to Grove and said, “I thought it was the killer who was fishing for

you

.”

you

.”

Grove didn't answer.

He just stared at that same swirling black cauldron of a southern sky.

Â

Â

“Michael, what is it? What's wrong!” Maura shook him, felt his pulse racing in his neck, wondering if this was epilepsy, thinking that he might bite his tongue off if she didn't do something quick.

Outside, the winds howled and yammered against the shuttered glass. As if answering it, Doerr went into wilder spasms on the floor, trying to make words come out but merely grunting and groaning inarticulately: “

Rrrrrâhhrrrrârrrrrrrr! Hhrrrr! Rrrrrrrrrrrrrr!”

Rrrrrâhhrrrrârrrrrrrr! Hhrrrr! Rrrrrrrrrrrrrr!”

“It's okay, it's okay, it's all right, Michael, I'm here, it's all right,” Maura softly reassured him as she stroked his trembling shoulders and tried to figure out what to do, what to do,

what to do

. “We'll get an ambulance, don't worry, you're gonna be fine.”

what to do

. “We'll get an ambulance, don't worry, you're gonna be fine.”

“

RrrrhhhhhhâRrrrrr!”

RrrrhhhhhhâRrrrrr!”

Maura sprang to her feet and frantically scanned the bungalow for a phone. She saw none in the living room. Michael had gone quiet on the floor next to her. She knelt down again, felt his pulse. His heart thumped irregularly in his chest, his breathing shallow yet steady.

“

Phone, phone, phone, phone, phone.

” Maura rose to her feet again. She saw a wall unit out in the kitchen mounted to the side of a cabinet. She went out there, snatched the phone off its cradle, and dialed 911.

Phone, phone, phone, phone, phone.

” Maura rose to her feet again. She saw a wall unit out in the kitchen mounted to the side of a cabinet. She went out there, snatched the phone off its cradle, and dialed 911.

“Shit!”

The recording crackled in her ear: “Due to the high amount of activity, all lines are currently busy. Please try again.”

She pulled her cell phone from her pocket, then looked at the tiny liquid crystal display. The indicator told her she had no connection, no cell strength whatsoever.

Something crashed in the backyard, and made her jump and let out a little cry of nervous tension. She searched for the source of the noise. Through the rear windowâthrough a gap in the ruffled curtainsâshe saw a broken trellis tangled with bougainvillea vines turning cartwheels across the grass in the wind.

The trellis slammed into a tree and shattered.

A sinking feeling gripped her for a moment, weighing down on her, a sense of being trapped. Fiona was breathing down on the city now, and Maura had no idea what to do. She knew she couldn't just leave Doerr here in this conditionâwhatever that condition might be. Plus, getting back in her car and driving around town, looking for an emergency room, seemed dangerous if not downright insane.

She went back into the living room and checked Doerr's vitals. He seemed okay. Still breathing steadily. But something caught Maura's eye then, something visible beneath Doerr's Tulane sweatshirt that gave her pause.

In all the excitement and writhing and wriggling, the sweatshirt had hiked up a little, exposing a couple of inches of the young man's tummy. A thick scar like a rubber worm peeked out from under the sweatshirt. It was so prominent, so severe, so

ugly

, that Maura instinctively yanked the sweatshirt up over the rest of Doerr's midsection.

ugly

, that Maura instinctively yanked the sweatshirt up over the rest of Doerr's midsection.

“

Oh my God.”

Oh my God.”

Maura stared at the scars, not fully comprehending their origin. Were they surgical scars? No. They were too ragged, too imprecise. They were also pink and shiny enough to be inflicted within the last year or two.

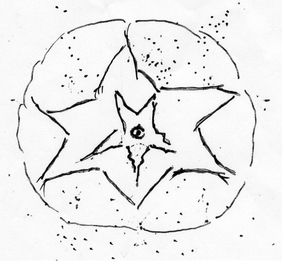

They formed a strange topography of slashes like this:

Another noise shook Maura out of her daze. Outside the front shutters, the wind rattled the hedges and roared across the neighborhood, through the high-line wires and treetops. It made a dissonant, whining noise. Rain began lashing the front windows in waves like angry cymbal crashes.

“Okay, okay, okay, okay, okay,” she muttered nervously under her breath as she lowered the sweatshirt and weighed her options. If she

had

to, she could stay here and wait out the first wave of the storm. She could at least stay with Doerr until he recovered or until Maura managed to get through to an ambulanceâwhichever came first. Had she given Grove the address? She couldn't remember.

had

to, she could stay here and wait out the first wave of the storm. She could at least stay with Doerr until he recovered or until Maura managed to get through to an ambulanceâwhichever came first. Had she given Grove the address? She couldn't remember.

She looked at her watch.

It was 1:37 p.m.

Less than nine hours now until Fiona was scheduled to arrive in all her horrible glory. It seemed like plenty of time, but it really wasn't. The winds were already making crosstown travel hazardous. Maybe it was time to find a safe place in which to wait things out.

She started searching the bungalow for a crawl space or some kind of reinforced area in which to huddle. She tried to remember if she had seen a storm cellar door outside, maybe along the base of the house in the backyard.

Minutes later she found the secret door embedded in the back wall of the pantry.

The door was locked.

It was ten minutes to two o'clock.

Â

Â

Halfway between Montgomery and Mobile, about two hundred miles northeast of New Orleans, in the billowing sheets of rain, Grove and Kaminsky saw the chaser lights of a state trooper's prowler approaching in the flickering blur behind them. This happened at almost precisely same moment that Maura County was stumbling upon the secret room in Michael Doerr's apartment (at 1:53 p.m. central standard time, to be exact).

At first Grove thought the trooper might be on his way somewhere else, to some storm-related emergency, or to some evacuation center somewhere to provide help with the exodus north. But as the boiling lights bore down on them, Kaminsky said, “Oh hell, Grove, what have you gotten me into now?” The trooper's headlights started flashing, and Kaminsky reluctantly pulled over.

The trooper took his sweet time getting out of his prowlerâhe was probably running checks on the Russian's federal plates. While they waited, Grove and Kaminsky argued about what they should say or do. They had been tooling along at over ninety miles an hour, so there was a good chance they would simply be given a ticket and be on their way. But Grove suspected there was more to this encounter than a speeding ticket. In fact, he had been having premonitions all day.

Without the buffering effect of his medication, Grove's mind had been seething with dread-saturated noise. Fragmented visions of that eerie white dust devil from the desert kept rearing up in Grove's peripheral vision. Memories of his mother's mystic babbling throughout his childhood echoed in his brain, her tales of apocalyptic angels fighting each other on barren, wasted lands devastated by plague and natural disasters. Grove even remembered one particular story of a river of blood heralding the dark god of the underworld, who had returned to earth to bring about a new age of darkness and misery. Vida Grove's personal cosmos was a mishmash of African tribal lore, Old Testament Catholicism (probably from the missionaries), and her own brand of quirky superstition. But more than anything else, the image that haunted Grove was that single glimpse of a flock of blackbirds madly circling a cage of wind, trapped forever in a moving prison of calm.

At last the trooper emerged from the prowler and splashed through the rain toward the Jeep with his hat down and collar up, his face grim and stony in the shadow of his Stetson's wide brim. Kaminsky rolled down his window, greeted the trooper, and started saying how sorry he was to be going so fast but he and Grove were on a government job and they had to beat Fiona to New Orleans or they were in deep “manure.” The trooper listened with monumental patienceâespecially considering the fact that he was standing in the rain. When Kaminsky was done, the trooper politely ignored it all and said he was going to need to see the Russian's license and registration. Kaminsky complied.

Then the trooper said he was going to need both Kaminsky and Grove to go ahead and get out of the vehicle and come back to the prowler.

Grove and Kaminsky did what they were told. They sat in the rear of the prowler, behind the screened safety partition like two common criminals, wondering what the hell to do now, while the trooper searched the Jeep. Sitting there in the noisy silence of the prowler, the rain a barrage of bullets across the vehicle's roof, Grove asked Kaminsky to let

him

, Grove, do the talking when the trooper returned. The Russian said that was fine with him, and when the trooper did return, Grove launched into a long explanation about being a consultant for the bureau, and being on special assignment. The trooper, ever courteous, ever patient, as unmovable as a granite milestone, listened to it all and then said he was going to need Grove to stop talking for a minute while he asked a few questions.

him

, Grove, do the talking when the trooper returned. The Russian said that was fine with him, and when the trooper did return, Grove launched into a long explanation about being a consultant for the bureau, and being on special assignment. The trooper, ever courteous, ever patient, as unmovable as a granite milestone, listened to it all and then said he was going to need Grove to stop talking for a minute while he asked a few questions.

It turned out that the bureau was the reason that the trooper had stopped the Jeep. Evidently a deputy sheriff from Ulmer's Folly by the name of George Stinsonâhe of the Fuller brush mustache and racist looksâhad called the North Carolina Bureau of Investigation only minutes after Grove and Kaminksy had roared away from Eve's ground zero. Accusations had flown back and forth that Grove was concealing evidence, or something to that effect, and now a bulletin had circulated throughout the Deep South that Grove should be apprehended and brought in for questioning. The trooper explained all this in his courteous monotone, and Grove kept breaking in and saying, “Trooper, I know you're just doing your job, but if you would just please contact a gentleman at bureau headquarters in Quantico named Tom Geisel, a section chief there, he will clear us.”

Other books

Closer Home by Kerry Anne King

Realm of the Dead by Donovan Neal

Tossing the Caber (The Toss Trilogy) by Craig, Susan

The Book of Trees by Leanne Lieberman

Beyond the Shadows by Cassidy Hunter

The Taste of Conquest by Krondl, Michael

Love's Awakening by Stuart, Kelly

Bloodlands by Cody, Christine

Summer Ruins by Leigh, Trisha

Steel and Lace (Lace Series) by Leigh, Adriane