Two Souls Indivisible (10 page)

Read Two Souls Indivisible Online

Authors: James S. Hirsch

Halyburton himself had already recognized the enemy's motives: if the Vietnamese couldn't induce him to cooperate through harassment, abuse, and isolation, they would lock him up with a disabled black man and force him to care for that person or watch him suffer and possibly die. Either outcome, they believed, would be torment. The prison officials knew that Halyburton was from the South and that his older black cellmate would have military seniority over himâa reversal of authority for any white Southerner. They had also primed Cherry to distrust white Americans. During his interrogations, they repeatedly told him that whites were racist, that they were colonizers, and that he had far more in common with the colored people of Asia. They also invoked Malcolm X, the militant black leader who had been an early critic of the war. In 1964 he said his government was the most "hypocritical since the world began" because it "was supposed to be a democracy ... but they want to draft you ... and send you to Saigon to fight for them," while blacks still had to worry about getting "a right to register and vote without being murdered."

Had Cherry accepted these sentiments, the racial divide between him and Halyburton would have been insurmountable. But Cherry was less concerned about his government than about this stranger in his cell. On their first full day, Halyburton wasn't acting like a racist or a French spy. His communication through the wall with other Americans perplexed himâhow could a spy do that?âbut Cherry still didn't believe that he was a Navy lieutenant.

His skepticism lessened when Halyburton talked about the most obvious thing they had in common: they had both been shot down over North Vietnam. As it happened, the shootdowns occurred five days apart in roughly the same area, about forty miles north or northeast of Hanoi. "Maybe the same gunner got both of us?" Halyburton said, causing Cherry to chuckle. Each man described his encounters with the peasants and militiamen in the countryside, and the similarity of their experiences reassured both men about the identity of the other.

Their suspicions were further dampened when they began naming the other American captives they knew. Halyburton shared these names with Knutson, who in turn named the captives he knew. This process confirmed a basic military tenet: find out who's been injured or captured so you leave no man behind. When the discussion drifted away from military matters, Halyburton mentioned several counties in his home state of North Carolinaâall familiar names to Cherry, whose father had been born in North Carolina and who grew up in Virginia.

Their forced intimacy evolved into an atmosphere of tolerance. They shared a rusty wastebucket, for example. When one was using it, the other stood in the opposite corner, his eyes averted. At least Halyburton's dysentery soon passed, making a terrible experience a bit less awful.

Their conversation became more relaxed, and Halyburton made his first offer of assistance.

"When did they let you bathe, wash up?" he asked.

"Bathed! I haven't bathed since I've been in this camp."

"Well, you should go every three or four days. I'll ask the guard."

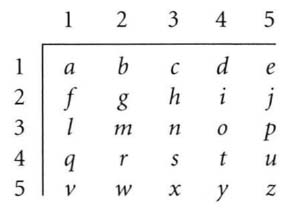

In the early days, Halyburton taught Cherry the tap code, a means of communication that integrated him into the society of captives while also eliminating any distrust between the two men. Halyburton had discovered the code in Heartbreak. Visiting the washroom, he saw that someone had inscribed on the wall a matrix with five rows across and five rows down, a different letter in each position, and realized it was a tap code. Most of the inmates at Heartbreak ignored it, for they could usually talk to one another, but Halyburton worried that the time would come when that wasn't possible. He wrote the matrix on the liner of a cigarette pack and became one of its most avid practitioners. Learning the code gave him a chance to exercise his mind, and it was an act of defiance against his captorsâin his words, "part of the tradecraft of being a prisoner."

To use the code, a person identified a letter by tapping out two numbers, the first giving the horizontal row number, the second, the vertical column number. A favorite message was 2â2 (G); 1â2 (B); and 4â5 (U)âGBU, an abbreviation for God Bless You, which became the universal signoff among the Americans.

The matrix had been carved into the wall by Air Force Captain Carlyle Harris, who understood that the Americans could organize and resist only if they could communicate. When he was in survival training, an instructor had showed him the code during a coffee break, and this casual reference proved to be the lifeblood of the POWs in Vietnam. Whenever a newcomer arrived, the other prisoners' first responsibility was to teach him the code. Sometimes the Morse Code was used to explain it. Sometimes notes were slipped into rice bowls or wastebuckets. An American on the floor in one of Hoa Lo's torture rooms could find the matrix carved underneath a table with the words: "All prisoners learn this code."

Tapping became so routine, so pervasive, that many of the POWs could click as fast as they could think. Some spent years tapping to each other without ever seeing their partner; others developed playful shortcuts. Before two POWs went to sleep, one would tap "GN" (goodnight) and the other, "ST" (sleep tight), which would prompt the first person to respond "DLTBBB" (don't let the bedbugs bite). With only twenty-five slots, the matrix had no "k," forcing tappers to substitute "c." Thus, a popular transmission was "Joan Baez succs," sent after the Vietnamese played a tape of the American antiwar activist through the cells' loudspeakers.

The code was later adapted to different settings. A POW walking through a courtyard could use hand gestures like a third base coach to spell out wordsâscratching his head meant row one; touching his shoulder, column threeâand other prisoners could watch from their cells. What the enemy may have thought was a nervous tic was actually a communication channel and a source of unity among the Americans.

To teach Cherry the code, Halyburton used cigarette ash to draw the matrix on toilet paper. By now he believed that Cherry was indeed an Air Force pilot and recognized that he had to learn the code. But Cherry saw a much deeper significance in his tutorial. Having watched and listened to Halyburton's "conversations" with Knutson, he knew they used the code to transfer classified information, so Halyburton would teach it to him only if he trusted him explicitly. Moreover, Cherry had not spoken to any Americans since his capture, so learning the code was like a child's learning to talkâhaltingly, he got his voice.

He made mistakes while practicing, confusing the horizontal numbers with the vertical.

"What the hell is that?" Halyburton asked in mock anger after Cherry tapped a message.

"That's how you taught me," Cherry said.

"Well, you learned it outta phase." He could needle Cherry about the error without offending him.

Cherry could now be assimilated into the rest of the prison and take an active part in resisting the enemy. In his eyes, Halyburton's efforts were the act of a patriot. No spy would lend that type of assistance.

Even in a two-person cell, a chain of command was essential.

In every military organization, a command structure ensures accountability and discipline: you follow your senior officer or you're gone. In a POW camp, the structure provides a cohesive front against the enemy and reassures the prisoner of his military status. The Code of Conduct specifies that a POW must adhere to senior authority, which increases the chance of survival for himself and his cohorts.

In Vietnam, the POWs decided one chain of command should exist for all the services, not separate lines for each branch. Seniority was determined by rank at the time of shootdown, though promotions while in captivity were also considered. Sometimes the Vietnamese tried to undermine the command structure by segregating the senior officers or identifying a junior officer as "room responsible," but prisoners found other ways to communicate to preserve the chain. As long as communication was possible, each cell, each cell block, and each prison had an inviolable chain of command.

Once Halyburton accepted that Cherry was a major, that made him the cell's junior officer by two ranks. He privately noted the oddness of that arrangement, but Cherry's accommodating styleâhe didn't boss or bully or even give ordersâeliminated any real concern. Cherry led by example and provided guidance instead. During a joint interrogation at Christmastime, for example, the Vietnamese offered the men candy and extra cigarettes. Halyburton looked at Cherry, who nodded, and Halyburton knew he could accept. It was a small gesture, perhaps imperceptible to the enemy, but still a significant departure from Halyburton's past.

Halyburton grew up in Davidson, North Carolina, a small college town where front doors were never locked and a peeping Tom signaled a virtual crime wave. Only twenty miles from Charlotteâthe lousy roads made it a long twenty milesâDavidson considered its isolation part of its charm. It took snobbish pride in being an intellectual redoubt in the Carolina Piedmont, a hamlet of inquiry amid large oak trees, blooming azaleas, and crickets. Poetry readings, foreign films, international musicians, and renowned ministers were all part of campus life, and during Porter's teenage years, Robert Frost, Ogden Nash, Carl Sandburg, Isaac Stern, Louis Armstrong, and Dorothy Thompson passed through town.

The influence of the college probably made Davidson more racially tolerant than most of North Carolina, but it still resisted desegregation and civil rights. To Porter, overt signs of racism abounded. His friends called Brazilian nuts "nigger toes," and adults used racial epithets. He saw a merchant use a cigarette to burn a black youth he suspected of mischief. On Halloween, he and his friends were allowed to visit only those houses owned by whites. The black barber would cut the hair only of white patrons; his customers would have gone elsewhere if he had used his scissors on the head of a black man. In 1955, when Porter was fourteen, the town newspaper ran a front-page editorial outlining its opposition to integration, citing the Negroes' alleged stunted intellectual development, their propensity for crime, and their loose morals. "Many white persons believe that morals among their own race are lax enough without exposing their children to an even more primitive view of sex habits," the

Gazette

said.

While such views may have reflected the attitudes of many Davidsonians, they were not held by Porter's family, whose decency and decorum produced a different kind of racismâless hateful but in some ways more insidious.

Porter lived with his mother and grandparents. His parents had divorced when he was very young, and he neither saw nor spoke to his father. His principal role model (and his namesake) was his grandfather William Porter, a short, stout figure whose progressive ideas sometimes caused him trouble. In 1921 Davidson College hired him as a biology professor, but after he taught evolution, he was reassigned to the geology department. Passionate about self-improvement, he read the Bible in Urdu, worked complicated crossword puzzles called anacrostics, and watched television without the sound. "If I ever lose my hearing," he explained, "I'll be able to read lips."

William Porter employed a black domestic for many years and treated her kindly, paying for her and her sister to attend beauty and nursing school. Each Christmas their elderly father would come to the house for his gift; one year when he came to the back porch, Porter said, "You can come to the front door and get it." He would never have felt obliged to give school funds or a holiday gift to poor whites, who, he believed, could earn their money through hard work. Blacks were different. They needed help, and it was the responsibility of good whites to provide it.

To young Porter, his grandfather, as well as the entire community, reinforced the idea that blacks were limited. Whites held jobs that required creativity and intelligenceâprofessors, writers, doctors. Blacks worked as janitors, postal clerks, cooks, garbage collectors, and yardmen. Their labor was indispensable to the functioning of any town, so they should be treated respectfullyâbut not equally. In his own house, blacks could enter through the front door, but they were not allowed to use the same bathrooms.

Halyburton, through his segregated high school, college, and military training, paid little attention to the civil rights movement or to its increasingly strident protests. The marches, the sit-ins, the freedom rides: they happened in the South but were not of his world. In his poems and other writing, Halyburton showed his sensitivity to many thingsâhis friends, his family, the seasons, the environment, his own emotions. But on race, he was comfortable with the status quo. His attitudes were reaffirmed on the

Independence,

where white officers flew magnificent jets while enlisted blacks washed clothes, fixed meals, and tightened screws. Halyburton did not endorse the violent bigotry of cross burning and bludgeoning but embraced the soft prejudice of paternalism. He was proud of what he considered his grandfather's racial beneficence, yet ignorant of his own condescension.

Until Halyburton met Fred Cherry, he had never deferred to the judgment of a black man. Even more unusual was his handling of all the domestic chores.