Two Souls Indivisible (16 page)

Read Two Souls Indivisible Online

Authors: James S. Hirsch

Cherry's sister, Beulah, raised him as a boy and was his principal advocate when he was a POW. Here they stand with Air Force Colonel Clark Price during Cherry's return to Suffolk, Virginia. Photo by the

Virginian-Pilot

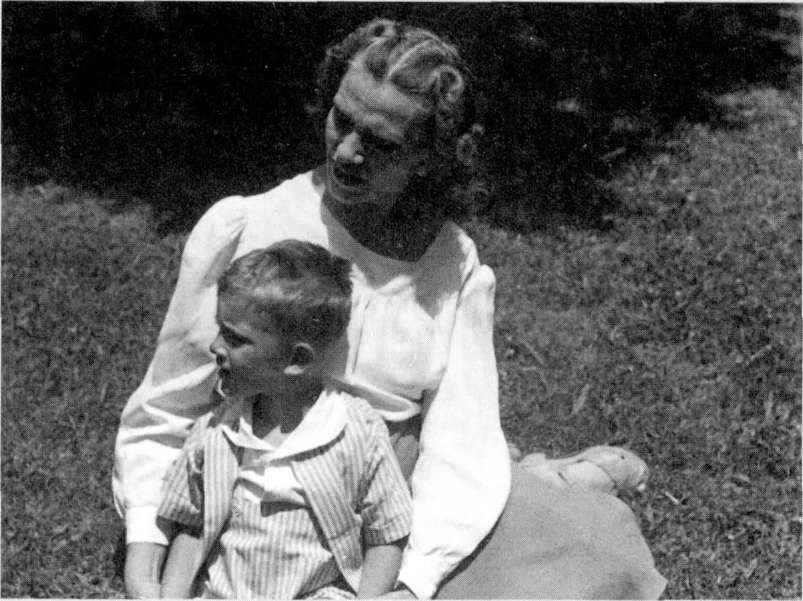

Katharine Halyburton, a fiercely protective single mother, taught Porter skills such as playing bridge, dancing, cooking, and sewing. Courtesy of Porter Halyburton

Commissioned as a Navy ensign in 1964, Halyburton was grateful that the Vietnam War would give him an opportunity to see combat. Courtesy of Porter Halyburton

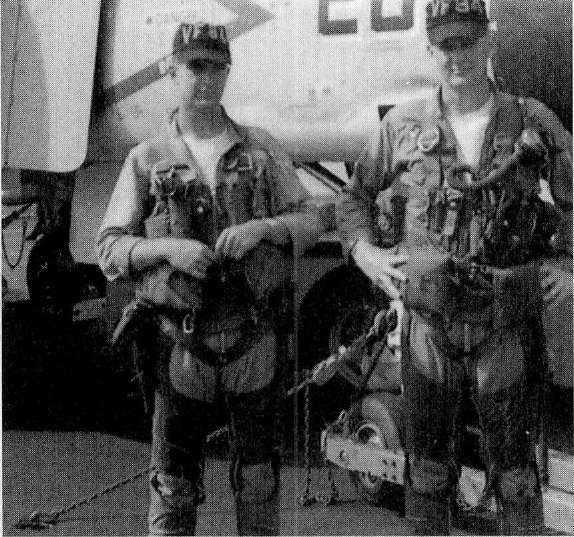

Halyburton (left), standing on the flight deck of the USS

Independence

in August of 1965, admired his pilot, Stanley Olmstead, whose good looks, humble roots, and aeronautic savvy seemed lifted from a military recruitment catalogue. Courtesy of Betty Dyess

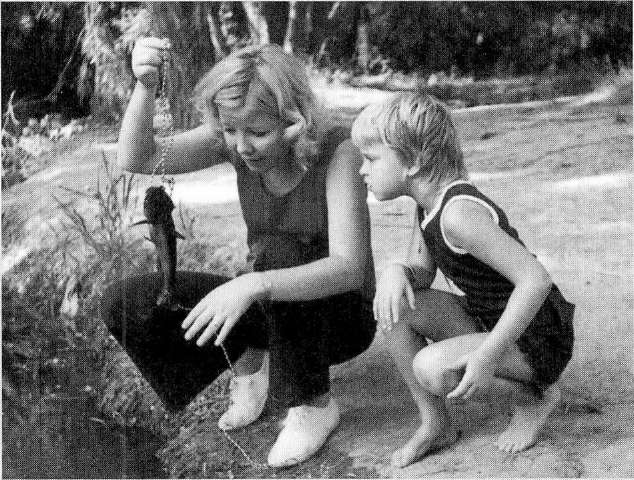

For more than seven years, Marty Halyburton raised Dabney by herself. She sent this photograph to Porter when he was in captivity. Courtesy of Porter Halyburton

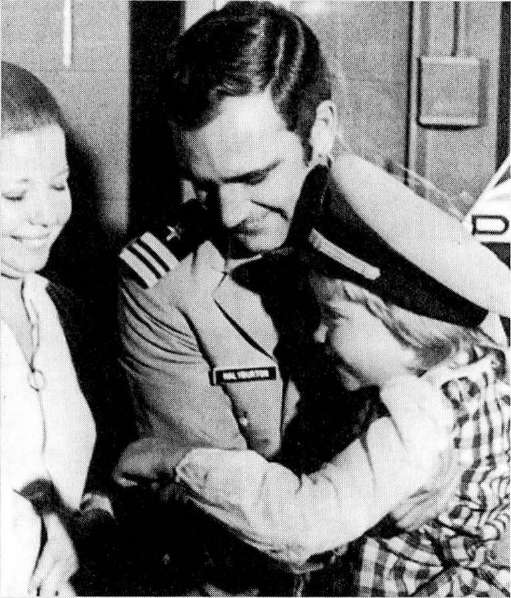

Porter, Marty, and Dabney arrived at Atlanta's airport on March 9, 1973. Associated Press

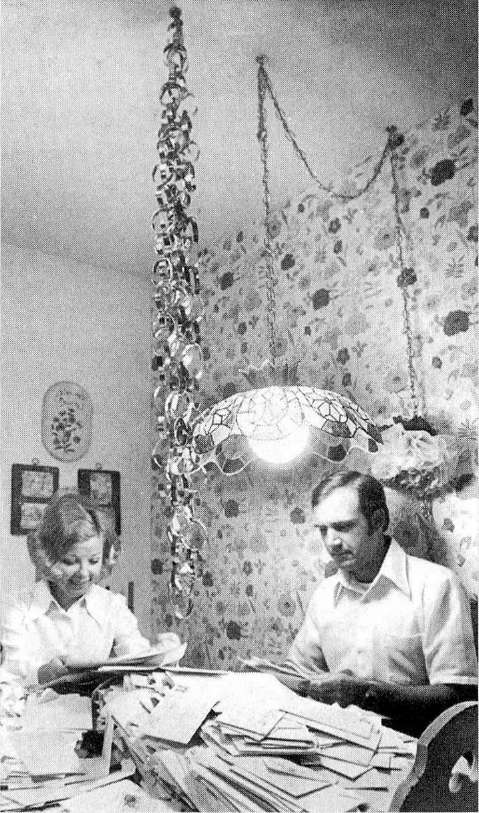

Supporters returned their Porter Halyburton POW bracelets, which were converted into a chandelier.

Courtesy of Porter Halyburton

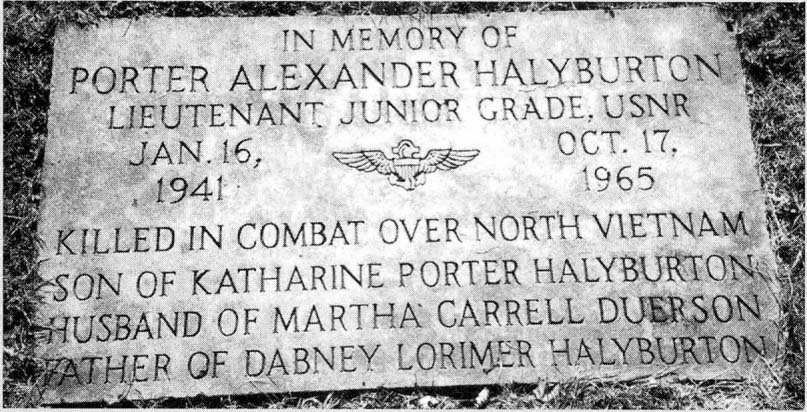

Halyburton's gravestone now rests in his backyard. Photo by James S. Hirsch

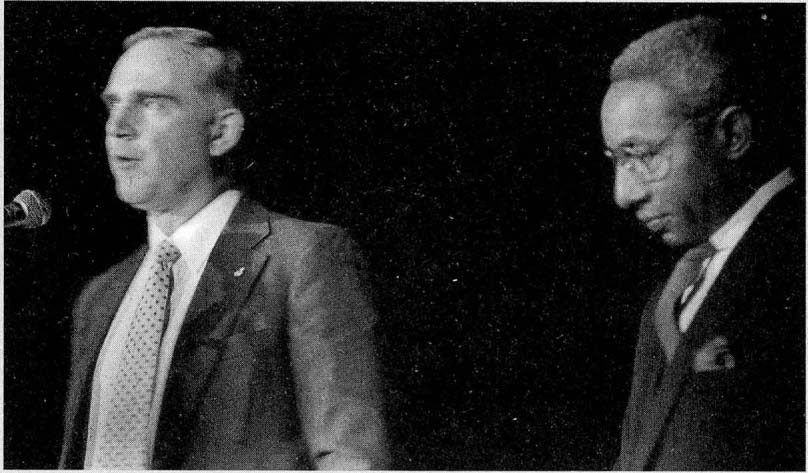

Halyburton and Cherry were honored at Davidson College in 1986. Courtesy of Davidson College

long, "angry red" incisions cut across Cherry's shoulder. It appeared that the stitches had been removed, but fluid was leaking through the scars. The shoulder itself looked no different than before the surgeryâwhich is to say, there was no shoulder. Where there had once been muscle was now a deep gorge, and Cherry still had no movement in his arm. It was evident to Halyburton that the doctors had tried to "reconnect" the arm to the shoulder but failed. He could also smell the gasoline.

Cherry's toughness amazed Halyburton; it was a toughness born of many early hardships. He was not going to die in Vietnam because he had had plenty of experience surviving.

The Cherrys' small wooden house, on a dirt road in the middle of corn and cotton fields, had no electricity or plumbing and little space, forcing several children to sleep in the living room. The roof leaked so badly that Fred would have nightmares of porous ceilings for the rest of his life. The family bought hundred-pound chunks of ice, chipped pieces off to refrigerate their food, then wrapped the rest of the block in newspaper to slow the melting. A coal stove warmed the kitchen in the winter, but there was no refuge from the summer's heat. The closest source of fresh water was a spring a half mile away, and Fred, riding his bike, carried home a splashing pail in each hand. When he woke up on Christmas morning, he found his own unwrapped shoebox with that year's treats: raisins, peanuts, an orange, an apple, maybe a little truck. Fred, knowing the family's meager resources, was grateful.

With inadequate water, sewage, and plumbing in and around the town of Suffolk, disease was rampant. Tuberculosis, pneumonia, heart attacks, and infant deaths occurred at alarmingly high ratesâtwo of Fred's siblings died as infants. Only thirty percent of black children in the area met the minimum health standards, according to a 1930 survey by the Virginia Department of Health. Dental care consisted of yanking out a rotting tooth, using black pepper to numb the pain.

Both of Fred's parents were descended from slave families in North Carolina. His father, John, was one-quarter Cherokee and looked like an American Indian, with swarthy skin, straight coal-black hair, and a flair for storytelling. A laborer and farmer, he was always juggling several small jobs while looking for something better. He would wake up at two

A.M.

and walk ten miles to a fertilizer factory. Fred knew if his father came home early, he hadn't been hired that day; if he came home late, he'd worked. Either way, he did the same thing the next morning. After a while, the factory gave him a regular job, and he rode to work with another employee, who had a car.

John also owned ten acres of land that grudgingly yielded corn, peas, beans, and potatoes, and Fred got an early taste of farming. At the age of five, he stood on his tiptoes to reach the crossbar of the plow as his father guided the family mule across the dry, hot fields; Fred hoped their work would produce a surplus. On those occasions, the entire family would shuck peas and beans in the evening, pour them into pint-sized baskets, and prepare them for sale. The following day John would lift Fred out of bed at three

A.M.

, wrap him in a burlap sack, and lay him on a mule-driven cart that now carried the food. On the four-mile trek to Suffolk, Fred would wake up beneath the stars and sit next to his father, sometimes eating strawberries that his mother had packed. A lantern attached to the cart illuminated the bumpy roads. Reaching Suffolk by daybreak, John would go from house to house, selling his baskets, as Fred rode the mule. If they sold their entire supply, they earned about five dollars; to celebrate, father and son would stop on the way home for a cookie or a soda and talk about what they would do on the farm that day.