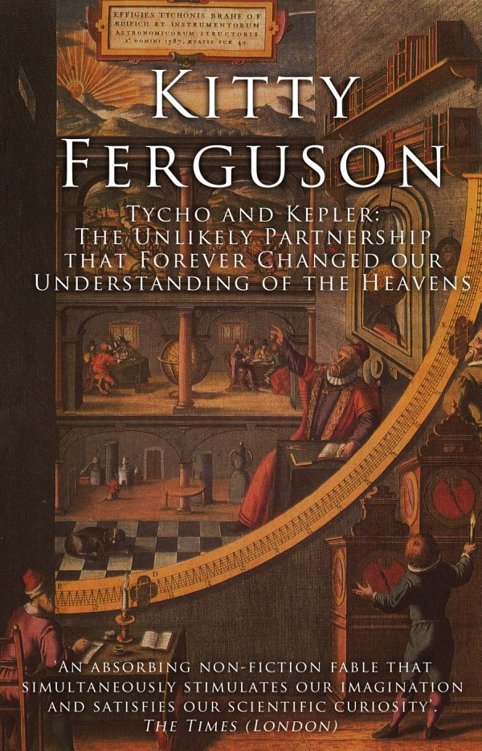

Tycho and Kepler

Authors: Kitty Ferguson

About the Book

The extraordinary, unlikely tale of Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler and their enormous contribution to astronomy and understanding of the cosmos is one of the strangest stories in the history of science.

Kepler was a poor, devoutly religious teacher with a genius for mathematics. Brahe was an arrogant, extravagant aristocrat who possessed the finest astronomical instruments

and observations of the time, before the telescope. Both espoused theories that seem off-the-wall to modern minds, but their fateful meeting in Prague in 1600 was to change the future of science.

Set in one of the most turbulent and colourful eras in European history, when medieval was giving way to modern, Tycho and Kepler is a double biography of these two remarkable men.

C

ONTENTS

2. Aristocrat by Birth, Astronomer by Nature

3. Behavior Unbecoming a Nobleman

4. Having the Best of Several Universes

8. Adelberg, Maulbronn, Uraniborg

10. The Undermining of Human Endeavor

13. Divine Right and Earthly Machination

17. A Dysfunctional Collaboration

18. “Let Me Not Seem to Have Lived in Vain”

21. The Wheel of Fortune Creaks Around

Appendix 2: Vocabulary of Astronomy

Appendix 3: Kepler’s Use of Tycho’s Observations of Mars

TYCHO & KEPLER

The Unlikely Partnership That Forever Changed Our Understanding of the Heavens

KITTY FERGUSON

To my sister, Virginia

A

CKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author wishes to express her heartfelt thanks to Owen Gingerich, whose scientific, historical, and bibliographical expertise is exceeded only by his patience, for reading the manuscript and offering corrections and advice; to Sir Brian Pippard, who offered extremely welcome insights on the work of Kepler; to Henrik Wachtmeister, whose family has owned Knutstorps Borg

since 1771, and who, after we met him unexpectedly in the churchyard at Kågeröd, graciously welcomed me and my husband and daughter to his home and offered me the use of an extraordinary seventeenth-century drawing of Knutstorps; to Yvonne Björkquist of the Tycho Brahe Museum on Hven, who showed us the sites of Uraniborg and Stjerneborg; to several helpful women at Benatky, whose names I never learned,

who did their best to overcome the language barrier and give us an understanding of the layout and history of the castle; to my husband, Yale, and my daughter, Caitlin, who shared these research adventures, navigated the back roads of Sweden and the Czech Republic, took photographs, and read the manuscript; to Anselm Skuhra, who knew the way through the labyrinth of European interlibrary loans

and risked his reputation with the University of Salzburg library when I failed to return books

on

time; to Justin Stagl, whose expertise in European social history rapidly cleared up many mysteries about calendar changes, the politics of the era, and the various names of the river that runs through Prague; to Karoline Krenn, who translated Kepler’s writing for me and whose expertise in the period

made her translation all the more discerning and accurate; to Gabriele Erhart, whose knowledge of European libraries, galleries, and museums and computer expertise were invaluable for locating illustrations; to Alena and Petr Hadrava, who helped me reach illustration sources in Prague; to James Voelkel, who helped me locate two difficult-to-find pictures; to my literary agents in Europe and America,

who read the manuscript at various stages and offered continual encouragement; and to my editors at Walker & Company in New York and Headline Publishers in London, for their splendid work on this book.

P

ROLOGUE

O

N

J

ANUARY

11, 1600, the carriage of Johann Friedrich Hoffmann, baron of Grünbüchel and Strechau, rumbled out of Graz and took the road north. The baron was a man of great wealth and culture, a member of an elite circle of advisers to Emperor Rudolph II of the Holy Roman Empire. Having fulfilled, for the time being, his occasional duties as a member of the Styrian Diet in the Austrian

provincial capital, he was returning to court in Prague, the glittering hub of European political and intellectual life.

Among Hoffmann’s acquaintances in Graz was a man considerably beneath his own station in society, an earnest young schoolmaster and mathematician named Johannes Kepler. Hoffmann was impressed by Kepler’s intense interest in astronomy, an interest he shared, and was aware

that Kepler’s talents far surpassed those of an obscure provincial teacher. He also knew that Kepler’s present situation as a Protestant in Graz was precarious, for the Counter-Reformation was raging there. Only Kepler’s position as district mathematician and the expertise he brought to composing annual astrological calendars that predicted everything from crops to wars had prevented his being expelled

from the city in 1598 along with other Protestant teachers and ministers.

Hoffmann

, for all his lofty status, was a thoughtful, kindly man. It had occurred to him that he might do his youthful friend a service by offering him a ride to Prague in his carriage at no cost to Kepler, who could ill afford such a journey, and an introduction to a far more experienced and distinguished astronomer who

had recently arrived there—whose nose was made of gold and silver.

The magnificent Tycho Brahe, the man with the extraordinary nose, was reputedly a difficult person. He had fallen foul of the Danish king and nobility and fled south as a princely refugee with his common-law wife, their six children, wagonloads of fabulous astronomical and alchemy equipment, and three thousand books. Hoffmann’s

own library was his passion. He was the sort of man to be drawn to an intellect such as Tycho’s and also to admire the brilliant networking that had brought Tycho to Emperor Rudolph. In Prague, Tycho Brahe had flowed through the court like fine honey. Rudolph, an eccentric collector of all manner of curiosities, had welcomed him and promised to support him and his learned pursuits in munificent

style.

Hoffmann’s invitation to ride in his carriage to Prague was a godsend to Johannes Kepler. There was no man in the world whom he so longed to meet as Tycho Brahe. Kepler had already made inept but not entirely fruitless overtures to him. Tycho had had kind, if condescending, words to say about Kepler’s first book and had hinted that he would welcome Kepler to join his coterie of assistants.

Alas, Tycho Brahe had been too far away in northern Europe and the journey prohibitively expensive. Suddenly, by the grace of God (Kepler had no doubt that God had a direct hand in such matters), Tycho had moved closer, and Kepler had a free ride to Prague. Never mind that it was a one-way ticket, that he had to leave his wife and stepdaughter behind, that Tycho might not be as eager to meet

him as he was to meet Tycho, that there was no guarantee a paying job would result. When the baron’s carriage drove out of Graz on January 11 and the driver set the horses to the road north, young Kepler was on board.

The journey took ten days, and Tycho Brahe was not in the city when they arrived. He was at Benatky nad Jizerou, a clifftop castle several miles to the northeast. Kepler stayed

for a few days as a guest in Hoffmann’s palace, considering how best to approach Tycho. Then on January 26, a letter arrived from the great man himself, who had heard that Kepler was in Prague. “You will come

1

not so much as guest,” Kepler read, “but as very welcome friend and highly desirable participant and companion in our observations of the heavens.” Kepler was apparently not to be just one

additional beginner assistant.

Nine days later, on February 4, carrying a glowing letter of introduction from Baron Hoffmann, Kepler rode out of Prague, this time in Tycho Brahe’s own carriage with Tycho’s son, also named Tycho, and an elegant young man named Franz Tengnagel. They crossed the Labe River at Brandeis, where the emperor had a luxurious hunting lodge, and continued through wooded

countryside. The trees, except for the numerous pines, were bare. It wasn’t until the next day, February 5, that they reached the first significant change in the landscape, the bluff above the Jizerou River. Poised on top, near the cliff edge, was a square three-story structure of generous but pleasing proportions. It was not the formidable, gloomy fortress some castles were. Perhaps Kepler saw—for

it had either been completed then or was in the process of creation—a wonderful fresco covering one entire exterior wall, showing hunting scenes with Emperor Rudolph prominently featured.

Kepler counted among his acquaintances several men such as Hoffmann who were of much greater social stature and wealth than himself. Nevertheless, the lord of Benatky whom he met that day came from a world

almost completely outside his previous realm of experience and, in spite of their shared scholarly interests, largely beyond his understanding. Kepler was a well-educated but poorly paid schoolmaster who had spent his childhood in an impoverished, dysfunctional family in small towns on the edge of the Black Forest. By

his

own description he resembled a little house dog, overeager to please—only

occasionally attempting to assert himself by growling or barking and, when he did, succeeding only in causing people to avoid him. Tycho Brahe was renowned throughout Europe as a prince among astronomers and an astronomer among princes; he was supremely well aware of his own superior intellect and status; and he regarded lesser men as just that: lesser men, some of whom he liked and treated well,

others not. At the time he met Kepler, he was feeling his age, fifty-three years. Bruised by recent defeats at the hands of enemies in Denmark, he was discouraged about the present state of his work. Nevertheless, he was on his feet again in a different court, lord of an imperial castle, with a promised income from the Holy Roman Emperor that was greater than that drawn by any other man at court.

His current public image in Prague was as an elegant and extrovert luminary. Some who had encountered him in different contexts knew he could also be an overbearing, combative, paranoid, and even somewhat malevolent figure.