Tyrant (41 page)

Authors: Valerio Massimo Manfredi

Dionysius pondered his words for a while, then said: ‘We’ll go overland.’

‘What?’

‘That’s right. We’ll build a slide, grease it well and drag the ships over it one by one, until we can lower them into the sea on the other side of the promontory.’

Leptines shook his head. ‘And that seems like a good idea to you? We’ll only be able to put one ship at a time into the sea. If the Carthaginians realize what we’re up to, they’ll sink them one by one as soon as they put out to sea.’

‘No, they won’t,’ replied Dionysius. ‘Because they’ll find a surprise waiting for them.’

‘A surprise?’

‘Have a screen of wicker and branches built along the shore of the open sea, three hundred feet long and twenty tall. You’ll see.’

The project was begun immediately: as a group of sailors raised the screen, hundreds of carpenters set to work building the slip, two parallel guides made of pinewood beams, which crossed over the promontory from the shore of the lagoon to the open sea on the other side. Others melted pig fat and ox tallow in huge cauldrons to spread over the guides to ease sliding. The ships were positioned on the slide and then dragged over it with ropes, each ship by its own crew, with five hundred men on each side.

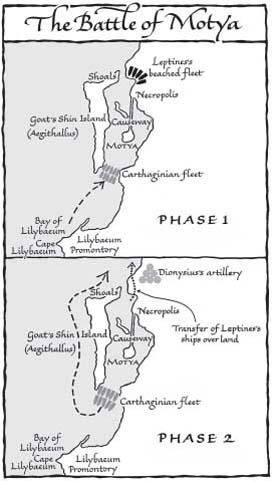

Construction of the slip was not visible from Motya but, when the ships began to be towed over the promontory, the sentries realized what was happening and sent news to Himilco that the mouse was fleeing the trap. The Punic admiral gave orders to man the oars and hoist the sails; they would advance in a northern direction and sail around Goat Shin island. This would keep them shielded until the last moment so that by the time the Syracusans saw them, it would be too late.

From the flagship, Himilco signalled for his ships to act in concert and stay together, so that the impact with the enemy fleet would be massive and synchronous. When the Syracusan warships finally came into sight, Himilco could count them: about sixty, making the ratio very favourable for him. He would destroy those, then go ashore and destroy the slip. At this point he would be free to blockade any ships which had been left behind in the lagoon, forcing them to rot or fight.

Having rounded the northern tip of the island, he turned sharply starboard towards the coast, and, when he was at a suitable distance, ordered the drummers to set a ramming tempo. At that point, the Syracusan ships, whose bows were turned west, put to starboard as if to make their way north, and Himilco mirrored the move. In doing so, his ships exposed their flanks to the coast, where a strange structure had now become perfectly visible: a sort of screen made of reeds, matting and even ship’s sails. And then the unforeseeable occurred: the screen fell, segment after segment, revealing a long line-up of mechanical monsters never before seen, missiles already in place, manned by dozens of artillerymen in combat position. A bugle sounded and, one after another, the enormous engines went into action. Himilco’s fleet was inundated by a hail of projectiles launched by the catapults. The ballistas, which had been adjusted to aim low, let loose a swarm of massive iron darts that broke through the keels under the waterline and swept away the decks, sowing death and terror. The machines had been timed for alternating launches: first the ballistas and then the catapults, as the former were reloading.

Meanwhile, the Syracusan vessels which had been pulled across the promontory put about in a wide circle to create a ramming formation. Leptines was, instead, still in the lagoon and headed south; he swiftly succeeded in breaking through the southern straits, overwhelming the meagre forces left there to garrison the outlet. His thirty quinqueremes, followed by the other ships, set out to close Himilco’s fleet in their trap.

The Carthaginian admiral, who had been warned by signals from the Motyans, put about, escaping the deadly attack of the artillery and put out to sea, just barely escaping entrapment between the contingents of Dionysius and Leptines.

Himilco thus abandoned Motya to her fate; such was the Carthaginians’ gratitude to those who had saved them from total disaster.

Cries of exultation exploded from the decks of the Greek ships and from the shore, where the formidable new siege engines had achieved such excellent results.

From the towers of Motya, the city’s defenders watched in anguish as the Carthaginian fleet disappeared at the horizon while, on the opposite side, the huge machines that had sent their enemy running were being dragged to the causeway, which now once again connected the mainland to their island. They knew they would all die. It was only a question of time.

One clean, clear morning at the end of the summer, after a night of wind, Dionysius gave orders to attack, and the siege engines lumbered down the causeway, squeaking and creaking.

The ballistas and catapults were the first to enter into action from the end of the causeway, targeting the city’s battlements and massacring her defenders. They were then hauled into position at the north of the island, where there was more room. There they were joined by the assault towers and battering rams.

The people of Motya knew full well what was in store for them. Many of them had taken part in the massacres of Selinus and Himera, and now they readied to defend their city to the last. They too had prepared a number of effective countermeasures. Long cantilevered planks were extended over the sides of the battlements from the wooden towers; caissons hanging from the ends of these boards held jars full of flaming naphtha and oil, which were hurled by the soldiers at the besiegers’ machines. The attackers reacted by covering the engines with newly-flayed skins, and put out any flames using buckets of water passed from man to man with great speed.

The walls were battered by the siege machines for five consecutive days, until finally one of the rams succeeded in opening a breach on the north-east section of the wall. The assault towers came forward and gangplanks were lowered so the Greeks could rush through the opening and penetrate the city, but the Motyans were advantaged by their narrow maze of streets. They offered furious resistance, fighting with grim determination house by house, alley by alley, raising barricades and hurling anything that could serve as a missile from the tops of the buildings, which were three or four storeys high, practically as tall as the towers.

Combat became fiercer and bloodier as the days went on. The assaults began at daybreak, continued relentlessly the entire day, and stopped only when darkness fell, but despite these constant attacks, the besiegers made little progress. Within that tangle of winding streets, amidst the towering buildings, they could not make their numerical superiority and the power of their weapons work to their advantage.

In the end, Dionysius had an idea. He gathered the leaders of the Selinuntian, Himeran, Geloan and Acragantine refugees in his tent, along with his brother Leptines and the commander of the assault troops, his old friend Biton.

‘Men,’ he began, ‘the Motyans have become inured to our daily attacks and they have sufficient time at their disposal to set up new forms of resistance. Their barricades built in the city’s narrow streets between the high walls of the houses are practically insurmountable. The Motyans know to expect our attacks by day from the assault towers positioned at the only breach, because they know there isn’t sufficient room to position them at other points of the walls. We must surprise them . . .’

He had one of his guards pass him a spear and used the tip to draw out his plans in the sand.

‘We will attack at night, using ladders, at a completely different point. Here. Biton, your assault troops will carry out the operation. Once you’re up on the walls, you should have no problem ridding yourselves of the few sentries that are usually posted in that area. You’ll use the ladders as footbridges to put you on the terraces of the houses nearest the walls. The men will enter through the roof windows and surprise the inhabitants in their sleep. More warriors will follow and take control of an increasingly vast area of the walls. An incendiary arrow will be the signal that you’ve succeeded in the operation, and at that point we will launch an assault from the breach with the bulk of our forces. The Motyans won’t know what to defend first, panic will spread and the city will be in our hands. Are you up to it, men?’

‘We’re raring to go!’ came the reply.

‘Fine. Leptines will transport the raiders with small flat-bottomed boats, painted black. You won’t need heavy arms; peltasts’ gear for everyone, cuirasses and leather shields. We’ll attack this very night; there’s a new moon and by moving quickly we’ll also ensure that word doesn’t get out. Men, the time has come to take your revenge. May the gods assist you.’

‘Will they succeed?’ asked Leptines when they’d left.

‘I’m sure they will,’ replied Dionysius. ‘Go now. I’ll wait here for your signal.’

Leptines went to the naval base to prepare the boats and ladders, then took the geared-up raiders on board. They were led by Biton, Dionysius’s trusted friend and a member of the Company.

Leptines put them ashore at a spot where the walls were almost lapped by the sea; they were far away from the breach and so the area was poorly guarded. The first group of raiders placed their ladders and climbed up in silence. After a short time, two of them leaned over and gestured for more to come up. The route was clear. In a matter of moments, fifty warriors were on the walls. They found no more than a few sentries on a stretch of about one hundred feet of the battlements, and easily took them out. Several were wearing the armour of the murdered Motyans and took their places. They were Selinuntians who spoke the language.

The men continued to urge their comrades up the ladders until there were about two hundred men gathered on the walls. They split into two groups: fifty of them remained to guard the point of ascent, where more warriors continued to arrive in a continuous stream from Leptines’s boats. The others laid out the ladders horizontally to reach the terraces of the houses closest to the wall and began to climb on to them, using the ladders as bridges. Then they opened the ceiling windows and dropped inside.

Surprised in their sleep, the inhabitants were massacred. Twenty men remained to garrison the terraces, as the ladders were extended to more houses and the assailants proceeded with their deadly mission. When the alarm sounded, the Motyans grabbed their arms and swarmed down into the streets, yelling loudly to wake up their comrades. Some of the houses had already been set aflame and many others were occupied by the attackers. More of them continued to pour over the walls, while others kept the breach under surveillance.

Biton launched the signal they’d agreed upon and Dionysius, already in position on the causeway, had the assault towers advance. Thousands of warriors invaded the city through the breach, easily overwhelming the one hundred or so defenders stationed there as guards.

Before long, contrasting rumours regarding multiple attacks at various spots of the circle of walls spread utter panic within the city, and the Motyans scattered in every direction, many of them defending the barricades that closed the entrances of the streets where their own families lived. When the common barrier was shattered, each of them fell back to the single barriers, until many found themselves – as had the Selinuntians so many years before – defending the doors to their own homes. It was the Selinuntians who were most murderous, and with them the Himerans. The shrieks of torment that reached their ears reawakened other screams in their minds: those of their dying wives and children, of their comrades massacred and tortured. Foaming with rage, out of their minds with bloodlust, excited by the mounting flames, they gave themselves over to merciless slaughter and to the sacking of that prosperous city, the hub of flourishing commerce between Africa and Sicily.