Ukulele For Dummies (41 page)

Read Ukulele For Dummies Online

Authors: Alistair Wood

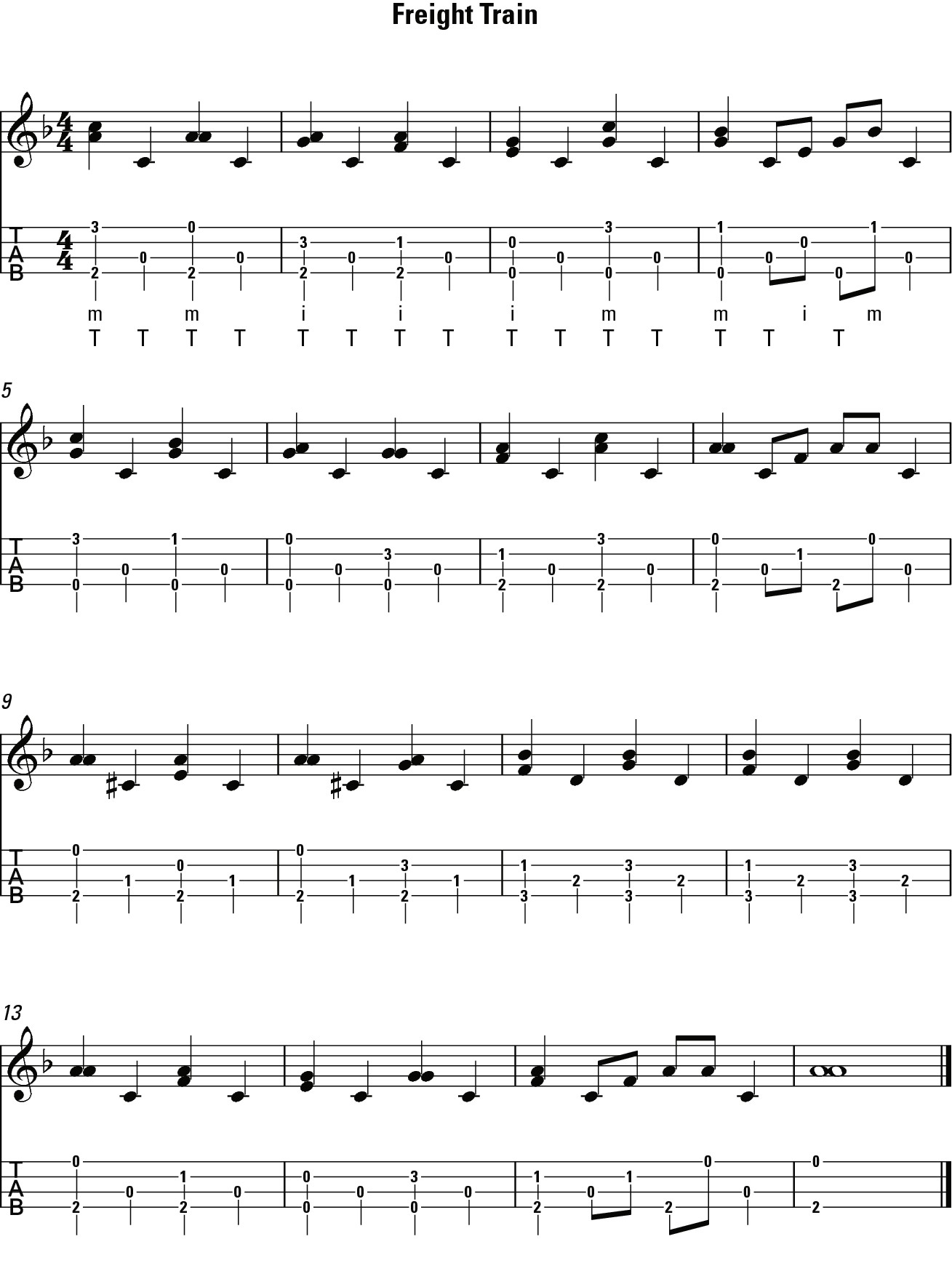

Fingerpicking to combine melody and chords

Many of the fingerpicking patterns in Chapter 8 can be used very effectively to combine melody and chords. The example in Figure 9-6 (âFreight Train'; Track 38) takes the alternate thumb-picking that I describe in Chapter 8. Your thumb alternates between the g- and C-strings while your index and middle fingers pick the melody notes on the E- and A-strings, respectively.

Many of the fingerpicking patterns in Chapter 8 can be used very effectively to combine melody and chords. The example in Figure 9-6 (âFreight Train'; Track 38) takes the alternate thumb-picking that I describe in Chapter 8. Your thumb alternates between the g- and C-strings while your index and middle fingers pick the melody notes on the E- and A-strings, respectively.

Figure 9-6:

âFreight Train' melody and chords.

Chapter 10

Picking Up Some Soloing Techniques

In This Chapter

Articulating fretting-hand techniques

Articulating fretting-hand techniques

Picking notes for solos

Picking notes for solos

Inventing your own solos

Inventing your own solos

I

n recent years, the ukulele has really come to the fore as a lead instrument taking solo lines, mainly due to the rise of large ukulele groups such as the Ukulele Orchestra of Great Britain and the Wellington International Ukulele Orchestra. To help you play solos, this chapter describes several great physical techniques (for both the fretting- and picking-hands) and a few useful short-cut methods for inventing solos using the notes from chords and from scales.

The ukulele isn't a natural lead instrument, because it has very little volume and

The ukulele isn't a natural lead instrument, because it has very little volume and

sustain

(the amount of time a note takes to go silent). When you're playing lead, therefore, using a larger, tenor ukulele is very useful. The tenor gives you a little extra volume and sustain as well as valuable noodling room for your solos.

Getting Articulated on the Frets

When you first start learning to play the uke, you pick or strum the notes (for example, as I describe in Chapters 4, 5 and 8). But you can also use your fretting hand to transition between notes without having to re-pick them with your picking hand. This approach adds new textures to the lines and can make rapid passages easier to play.

These fretting-hand techniques are called

articulations

and the term is perfectly chosen, because one of the aims of a great solo on any instrument is to recreate the sound of the human voice. Humans were deeply programmed â over centuries â to respond emotionally to the voice. Articulations recreate the kinds of slurs and trills that you experience with singing.

Hammering-on

A

hammer-on

is a way of moving from a lower note to a higher note. To play an open-string hammer-on you:

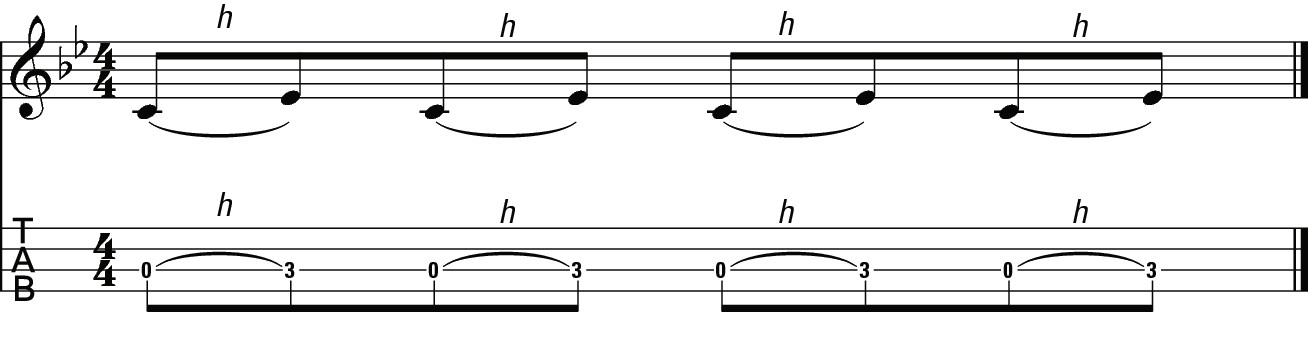

1. Pluck the open string as usual (the C-string in the case of Figure 10-1).

2. Leave the string ringing while you quickly bring the ring finger of your fretting hand down from a height of about half a centimetre (onto the third fret in this example).

Try to make most of the âhammering down' movement come from the knuckle â not your wrist â and land in the usual fretting position just behind the fret wire.

The word

hammer

is very apt because you have to bring your finger down quickly and firmly for the technique to work. In tab, a hammer-on is shown as a tie between the notes with an âh' above.

If you hammer down hard and cleanly enough, you should hear the string still ringing without you having to re-pick it.

If you hammer down hard and cleanly enough, you should hear the string still ringing without you having to re-pick it.

Figure 10-1:

An open-string hammer-on.

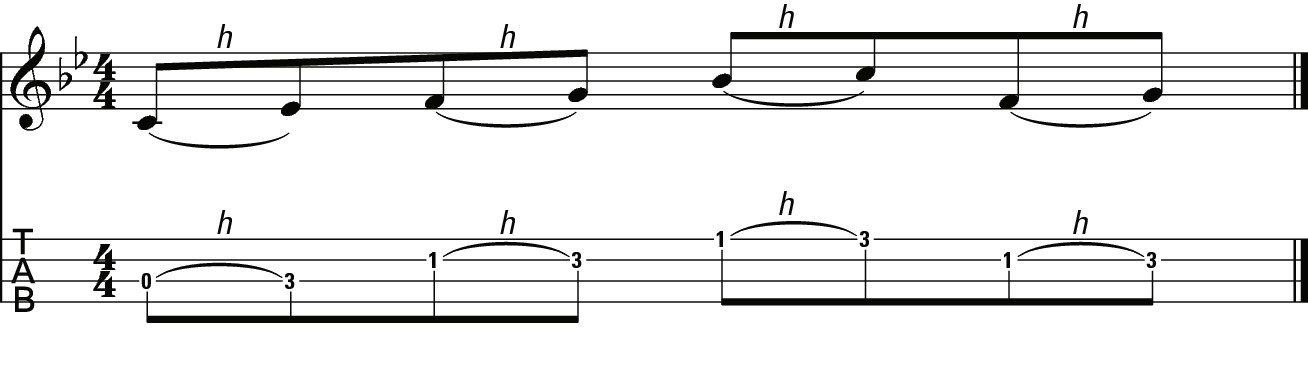

You can also hammer-on from fretted notes. The technique is exactly the same but you start with a fretted rather than an open string. The two types of hammer-ons are combined in Figure 10-2 and on Track 39, Part 1.

You can also hammer-on from fretted notes. The technique is exactly the same but you start with a fretted rather than an open string. The two types of hammer-ons are combined in Figure 10-2 and on Track 39, Part 1.

Figure 10-2:

Open and fretted hammer-ons.

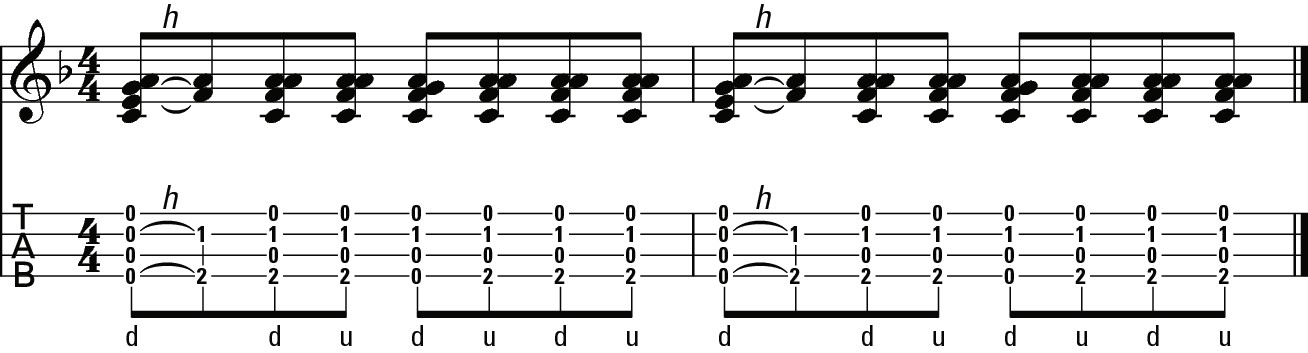

Hammer-ons can be very effectively adapted for use with chords: you strum the open strings and then hammer-on all the notes of the chords. In Figure 10-3 (Track 39, Part 2), you start by strumming the open strings and then hammering-on the notes of the F chord. You then strum the rest of the bar normally.

Hammer-ons can be very effectively adapted for use with chords: you strum the open strings and then hammer-on all the notes of the chords. In Figure 10-3 (Track 39, Part 2), you start by strumming the open strings and then hammering-on the notes of the F chord. You then strum the rest of the bar normally.

Figure 10-3:

Chord hammer-ons.

Alternatively, you can start with one or more of the strings fretted and then hammer-on the remaining notes in the chord: a partial-chord hammer-on. So you fret the E-string of an F chord, strum and then hammer-on the note on the g-string. Figure 10-4 (Track 39, Part 3) is a progression based on F and A with hammer-ons (and is a technique used often by Zach Condon of the band Beirut).

Alternatively, you can start with one or more of the strings fretted and then hammer-on the remaining notes in the chord: a partial-chord hammer-on. So you fret the E-string of an F chord, strum and then hammer-on the note on the g-string. Figure 10-4 (Track 39, Part 3) is a progression based on F and A with hammer-ons (and is a technique used often by Zach Condon of the band Beirut).