Ultimate Baseball Road Trip (18 page)

Read Ultimate Baseball Road Trip Online

Authors: Josh Pahigian,Kevin O’Connell

Cyber Super-Fans

Although we don’t usually spend our time patrolling the web-net for more Yankee coverage than our friends at ESPN.com already provide, we do recommend these excellent fan sites.

- The Yankee Tavern

- NYY Fans

- Pinstripe Alley

- River Ave Blues

A showman known as “Bald Vinny” Milano leads a host of happy hooligans in the right-field bleachers in performing the daily roll call. In the top of the first inning, they all stand and honor each Yankee starter by chanting his name until he turns around to acknowledge them with a wave, tip of the cap, or Nick Swisher–style salute. You don’t have to sit in the bleachers to get the effect; the whole stadium reverberates with the chorus of player nicknames. Hats off to the Bleacher Creatures for creating and maintaining a special tradition that enables them to interact with the players.

The outfield video boards combine to offer mock fireworks whenever a member of the home team hits a long ball. We got a kick out of the John Sterling “Swish-i-licious” graphic when the “Son of Steve” connected for a three-run shot into the right-field seats during our game. Then, when Mark Teixeira hit a grand slam an inning later, we chuckled along with the “Nice shooting, Tex!” graphic, even as we realized

we were watching a Yankee blowout. The Pinstripes led 14-2 and would go on to win 17-7. Not a good night to be a Red Sox or Mariners fan at Yankee Stadium.

They’re higher up than the jets that buzz Citi Field, but planes fly over Yankee Stadium all game long as they blast off from LaGuardia. And just like at the old Yankee Stadium, you can see the elevated subway cars rolling past the stadium through a gap in the right-field seats.

Even if the Yankees don’t have a fluffy mascot like practically every team does these days, they have bought into the idea of a nightly stadium race. This takes place on the video board, featuring the orange B train, the blue D train and the green 4 train. The cartoon trains race through Times Square and then into Yankee Country. We saw the 4 win by a nose, and wondered if the 4 always triumphed, since it’s the train most commonly used to access the Stadium. Then they posted the season standings and we saw that the 4 had 14 wins, the D had 15, and the B had 14. So, any train is a fair bet.

If you’re dismayed to find that most of the hot Rolex dealers and smooth-talking hucksters have been driven from Times Square, you can still get the chance to feel as though you’re gambling on a street corner when the nightly cap game takes place on the video screen. Guess which Yankees hat has the ball beneath it and you just might win a few bucks from the near-sighted slob sitting next to you. We bet a beer and Kevin wound up buying for Josh and our friend Joey Bedbugs. It was about time Kevin ponied up for a round anyway!

Sports in the City

The Yogi Berra Museum and Learning Center

8 Quarry Rd., Little Falls, New Jersey

In 1996 longtime Montclair, New Jersey, resident Yogi Berra received an honorary doctorate from Montclair State University. Two years later, the school opened a baseball park on its campus named after Yogi, and two years after that the Yogi Berra Museum and Learning Center opened. The museum features plenty of Yankees memorabilia as well as exhibits from the Negro Leagues and interactive exhibits for the kids.

Sports in the City

Babe Ruth’s Grave

Cemetery of the Gate of Heaven

Hawthorne, New York

For Bambino fans and those who simply enjoy an occasional graveyard jaunt, this burial yard twenty-five miles north of New York City makes for an interesting excursion. The massive and very scenic cemetery is where Babe Ruth (Section 25, Plot 1115, Grave 3), Billy Martin (Section 25, Plot 21, Grave 3), and MLB umpire John McSherry (Section 44, Plot 480, Grave 3) are laid to rest. You may recall that McSherry died on the field in Cincinnati on Opening Day of the 1996 season. But clearly Ruth’s marker is the prime attraction. The Bambino’s headstone reads, “May the divine spirit that animated Babe Ruth to win the crucial game of life inspire the youth of America.” When we visited, it was adorned by empty beer bottles, pictures of the Babe, pennies, flowers, an American flag, Yankee hats, baseballs, and Yankee Stadium ticket stubs.

Martin’s stone contains a quote from the four-time Yankee skipper: “I may not have been the greatest Yankee to put on the uniform, but I was the proudest.”

The fans get a kick out of a contest in which they show a Yankee star on the video board and then show four possible baby pictures on the screen. The fans have to guess which picture was the “Baby Bomber.” They showed Jeter when we were in town and we all got it wrong. Turns out he was a cute kid.

A lot of teams have a special local song they play over the P.A. system after the home team wins. It should come as no surprise that at Yankee Stadium, the voice of Frank Sinatra (who was actually from Hoboken, New Jersey) belts out “New York, New York.” The tune resonates throughout the stadium at a near eardrum-shattering decibel level as fans head for the exits.

We Had a Bedbug Scare

Our return trip to New York City took place more than a year after the well-reported bedbug outbreak of 2010. Nonetheless, the threat posed by the invasive nocturnal nibblers was still prominently placed at the front of Josh’s mind as he and his friend Joe Bird rolled into the Big Apple.

Kevin would be meeting us later. A hypochondriac by nature, Josh was only partly to blame for his bedbug worries, though. This is what happened: Prior to the trip, Josh took the lead on getting tickets and booking a hotel and, since Joe was coming along, Joe partook in the decision-making. Or, rather, Joe’s wife Carol did. Now, it should be mentioned that Carol is a lovely woman … a saint, actually, for putting up with Joe, who is not so quietly engaged in Stage Two of a five-stage plan he’s concocted to turn their otherwise tasteful Bellingham, Massachusetts, home into a Red Sox autograph shrine. Joe has already “decorated” his office and their bedroom and is working his way down the stairs toward the living room. Aside from being a supportive wife, though, Carol is also a bedbug alarmist of the highest order and her fear of the critters infected Josh. You see, when Josh originally booked a room at a venerable Times Square hotel at a surprisingly discounted rate, Carol’s response to Joe was, “You can go, but if you stay there I’m burning all your luggage when you get home and you’re sleeping in the backyard for the rest of your life.” As Carol sagely pointed out, Josh’s pick had five complaints against it on an Internet bedbug registry. And a stay there would have in all likelihood been disastrous.

So, we cancelled our original booking and opted for a more recently constructed hotel—a Red Roof Inn—within walking distance of Citi Field in Flushing. Upon arriving, we were dismayed to bump into an exterminator at the front desk. He was toting a pump and hose and had evidently just finished whatever business he had at the Red Roof, because the attendant at the desk was signing his digital device to verify he’d completed a spray.

“We’re definitely not mentioning this to Carol,” Joe said.

“Wait till Kevin hears,” Josh replied.

So, Josh and Joe checked in and proceeded to turn both of their beds inside out looking for blood-stained excrement on the mattress as Carol had advised, and/or for a nest behind the headboard. Joe disassembled the beds with a ratchet set he had brought just for the purpose. No evidence was found, though. The Red Roof was clean.

Upon arriving that night, Kevin shrugged off the concern. “Bedbugs, schmedbugs,” he scoffed. “You East Coasters are so uptight.”

Fast-forward two days and two games. Despite July temperatures that surpassed 100 degrees Fahrenheit both days, we stomped all over the city. We also caught a two-hour National League game, and a four-hour-plus American League game. After the marathon in the Bronx, we returned to our rooms at 1:00 a.m., at which time Josh just happened to notice about a dozen red marks—that looked a lot like bites—on both of his ankles.

“That’s heat rash,” Kevin said immediately. “I’ve had it before. Take a cold shower and it’ll be gone by the time we check out.”

But Joe and Josh wouldn’t hear it. In their minds, they had to be bedbug bites.

“Carol’s never gonna let me come to New York again,” Joe lamented.

“Help me open this window,” Josh rejoined. “I’m gonna heave my luggage off the balcony. Then tomorrow I’ll go to Target and buy new clothes to wear home.”

“East Coasters,” Kevin said dismissively. Then he went to his own room to bed.

While Joe and Josh spent two hours making use of the hotel’s WiFi, researching bedbug bite pictures and decontamination protocol, Kevin snored away in the adjoining room. Then Joe and Josh caught a few fitful hours of sleep on the floor.

The next morning, Kevin was refreshed. Josh and Joe were haggard, but they were all smiles too. Overnight Josh’s “bedbug bites” had pretty much disappeared. In the end, his affliction turned out to be a heat rash after all.

But just the same, you should probably check out the bedbug registry before booking your room in New York City. You can access the list of previously infected hotels at:

http://bedbugregistry.com/

.

TORONTO BLUE JAYS,

TORONTO BLUE JAYS,ROGERS CENTRE

A Dome with a View

T

ORONTO

, O

NTARIO

230 MILES TO DETROIT

290 MILES TO CLEVELAND

320 MILES TO PITTSBURGH

330 MILES TO COOPERSTOWN

B

ack when new ballparks were opening at a clip of one or two per year in the 1990s and early 2000s, it must have seemed to each baseball owner that all they needed to do was convince their local officials to pony up a friendly financing deal for a new yard and a future of ever-increasing revenue and ravenous fan support would be assured. At the time, of course, the US economy was humming along, or at least seemed to be, as Americans plunked down credit cards to fund lavish lifestyles that included far-reaching baseball tours that brought them to cities like Baltimore, Toronto, and even Cleveland, where new parks served as the centerpieces of urban renaissances. The hapless Indians sold out 455 games in a row at Jacobs Field. The Orioles’ Camden Yards was revealed as

the

display model for those seeking to bring retro-ballpark comfort and funk to their own cities. And the Toronto Blue Jays attracted more than four million fans per season (or a whopping fifty thousand per game!) while winning back-to-back World Series at the celebration of modern architecture known at the time simply as “SkyDome.” While we are thankful for the new generation of stadiums this boom-time brought us, we wonder if baseball’s owners ever stopped to consider how long (or short) the shelf life for some of their new yards might be. You see, somewhere along the way the owners started to take it for granted that all they needed to do was open the gates to their sparkling new digs and the fans would continue coming indefinitely. But as each one opened, the competition for travelers’ dough became fiercer. Fans suddenly had

many

new yards to visit, not just a handful. And many owners lost sight of their fan bases—their home folks—and neglected the necessity of putting a winning team on the field. That’s why the Pirates never parlayed beautiful PNC Park into a sustainable attendance surge and why the Orioles and Indians fell rapidly from the top of baseball’s annual attendance heap to the bottom. And it’s why Toronto has reverted to being a second-class baseball city once again, despite the promise it seemed to hold in the 1990s. The work-stoppage of 1994, which came when the Jays were two-time defending World Champs, and baseball’s abandonment of that other Canadian outpost, in Montreal, had a lot to do with the decline in many casual Canadian baseball fans’ interest in the American Game.

Today, no Major League stadium provides as great an example as Rogers Centre does of a city’s flailing baseball interest. Today, the Blue Jays struggle to draw half as many fans as they did when SkyDome was still a shiny new bastion of modern technology, and more importantly, the Jays were winning AL East titles.

As for the question as to why the stadium now known as Rogers Centre has lost its luster in the eyes of traveling fans, the answer involves the inevitable, but perhaps at the time of its construction unforeseeable, evolution of our ballpark preferences as fans. When Toronto unveiled its revolutionary facility midway through the 1989 season, many observers believed it would forever change the course of ballpark construction. And for a while it looked like they were right. At a time when many multi-purpose “cookie-cutter” stadiums were still in use, Toronto proclaimed its field capable of hosting professional baseball, football, and basketball. Not only was its stadium the biggest, baddest dome on the continent, but it came complete with a retractable roof. On nice days, fans would enjoy outdoor baseball (albeit, played on a rug). And on crisp Canadian nights, they’d enjoy indoor ball. The future had arrived and for once Canada seemed to be leading the way. It must have been a pretty good feeling, especially when road trippers from around the world made SkyDome one of the hottest new tourist destinations of the early 1990s. Just how in love with SkyDome were baseball’s fans? Josh recalls one popular sports-radio host in Boston calling for a “retractable roof stadium on the South Boston waterfront just like SkyDome” over and over again. Not just for days, but for years. And the guy wasn’t tarred and

feathered for daring to suggest Fenway should be replaced by such an ultra-modern facility. In fact, he had quite a following of like-minded thinkers.

With a successful team on the field, the Blue Jays set new American League attendance records four years running. For the first time ever, Torontonians could say their local nine played at the most popular stadium in North America. And baseball, which had seemed destined to forever play second fiddle in the Great White North to hockey and bigger-field football, seemed ready to compete for Canadians’ fancy. Torontonians loved their team and perhaps loved Sky-Dome a little more. What the good folks in Ontario didn’t realize, however, was that back in the States the fickle winds of change were a-blowin’ and they were about to shift in a completely different direction. The ballpark designers in Baltimore had a new vision, or rather, a retro-y new vision. And it was about to set dome-lovers everywhere on their ear. Oriole Park at Camden Yards opened three years after Sky-Dome, and as word of its delights spread, other cities across the United States began planning smaller, more intimate ballparks like the ones that ruled supreme during baseball’s glory years. Nosebleed seats, artificial turf, concrete construction, and symmetrical field dimensions fell out of favor as real grass, steel and brick, and quirky outfield nooks and crannies returned to their rightful places in ballparks from Seattle to Philadelphia.

“But we still have a retractable roof!” Canadians cried. “Let’s see you top that.” And top it the crafty Americans did. In the lower forty-eight, new ballparks sprang up offering the same safeguard against inclement weather as Sky-Dome, while also featuring full dirt infields and natural grass. In other words, these parks offered outdoor baseball, even when their lids were on. The good-hearted Canadians had been foiled by their North American allies again.

Kevin:

That was after losing William Shatner to American TV, Jim Carrey to Hollywood, Shania Twain to Dollywood, the Nordiques to Denver, the Jets to Phoenix …

Josh:

And your point is?

Kevin:

They’re pretty good friends to endure all the crap we put them through.

After losing a chance to three-peat when the 1994 World Series was canceled, the Blue Jays experienced a prolonged currency crisis as a weak Canadian dollar prevented them from competing for top free agents for several years. The fact that the Jays’ division included the two wealthiest teams in baseball also contributed, no doubt, to the growing disillusionment of Toronto fans. And before long, many of the converts to the American Game had soured on it. They said, “We’ve got hockey and curling. And three-down football! The Jays, well they can just take off, eh?” And so, sadly, the Jays now play before a 60-percent-empty Rogers Centre, struggling to draw two million fans per season.

Upon entering Rogers, fans will be impressed by the sheer size of it, even in comparison to the other retractable roof stadiums. But once the game begins, it is hard to overlook how far removed the Rogers experience is from the pleasure of enjoying a game at an idyllic American ballpark. It seems almost fitting by the time the later innings roll around that the Blue Jays kick off the seventh-inning stretch with a song other than “Take Me Out to the Ball Game.” But fans should not forget the important contribution this

stadium did make to the evolution of ballpark design. Prior to its existence, the only retractable roof facility in big league history was Montreal’s Stade Olympique, which eventually became a fixed dome due to its roof’s mechanical failure, and then later, became an open-air park when the roof was removed. Fans in cities like Seattle, Phoenix, Houston, and Milwaukee who are thankful their respective roofs retract should remember Rogers Centre. And they should pay it a visit. In fact, every fan should. In archaeology, they may still be searching for the missing link. But in ballpark construction, we know right where it is: on the shores of Lake Ontario in downtown Toronto, which we might add, is one hip city.

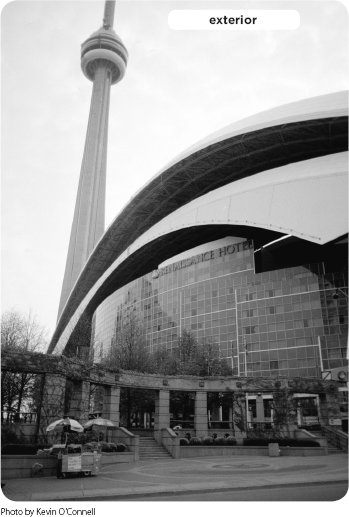

From the outside, Rogers is too big to photograph—unless your lens is as wide as Barry Bonds’ noggin. By the time you step far enough away to fit the whole structure in your frame, another building has inevitably blocked your view. Best to buy a postcard. And aren’t domes usually round or at least ovular? Rogers looks like a concrete block. Leave it to the Canadians to make a square dome. We don’t mean to disparage our fair friends to the north. Canada is a wonderful and peaceful nation with whom we are proud to share a border. It’s just that the Jays entered the American League the same year as Kevin’s beloved Mariners, and while Toronto was winning back-to-back World Series, the M’s were still in search of back-to-back winning seasons. It’s pure jealousy that prompts Kevin to kid. As for Josh, he’s angry there hasn’t been a

Strange Brew II

. On this point, Kevin agrees.

Inside Rogers the atmosphere resembles that of older-generation domes like the Metrodome and Kingdome, but on a much grander scale. The Astrodome was eighteen stories high. Rogers is thirty-one, which situates its roof nearly three hundred feet above the field. The extra space leaves room for five levels, several restaurants, and seventy hotel rooms that overlook the outfield.

Kevin:

A hotel

inside

the ballpark. What would Ty Cobb say to

that?

Josh:

Umm … how the heck should

I

know?

Kevin:

You really don’t get the concept of rhetorical questions, do you?

Josh:

I’m not sure. I suppose …

Kevin:

Never mind.

As for the roof, it doesn’t open all the way, but exposes about 90 percent of the seats to the sky when peeled back. Only the seats in center field remain under the hood—which consists of four panels, three movable and one stationary. When the roof retracts, the panels stack up on top of one another. Together they weigh twenty-two million pounds!

In 1995, two thirty-pound roof tiles fell during a game, injuring seven fans, but for the most part the roof has functioned well and left few injured fans in its wake. It takes about twenty minutes to open or close. If you’re in town on a nice day and you want to see this phenomenon, arrive a couple hours before the game and wait for it to retract. Or better yet, time your visit to the CN Tower next door so you can look down as the roof slowly uncovers the field. It’s really something to see.

The dome opened in June 1989, after Exhibition Stadium had served as the Blue Jays’ roost from the time the team joined the American League as an expansion franchise in 1977. A longtime football facility, Exhibition Stadium was modified to accommodate 43,737 baseball fans. It had artificial turf and was famous for its damp and chilly conditions beside Lake Ontario. It was not laid out well for baseball. The Grandstand roof covered the seats in left-field home run territory but not the ones around home plate, and some of the seats were more than eight hundred feet from home plate. Forget about bringing binoculars to the game. Fans needed telescopes to see the action from some of the seats.

Aside from the wind gusts, snowstorms, biblical rains, and flocks of dive-bombing seagulls that often thwarted the Jays’ hopes of playing ball during this era, the general shoddiness of Exhibition Stadium worked against the Jays as well. But sometimes their familiarity with the stadium’s flaws and its potential pitfalls worked in their favor. In 1977, for example, Baltimore manager Earl Weaver pulled his team off the field in the fifth inning, claiming that the loose bricks holding down the tarps on the bullpen mounds in foul territory posed a hazard to his outfielders. Amazingly, the Jays were declared winners by forfeit. But the fans, no doubt, went home feeling ripped off. And the Orioles had the last laugh. While the last-place Jays won only fifty-four games that year, the second-place O’s won ninety-seven.