Ultramarathon Man (14 page)

Authors: DEAN KARNAZES

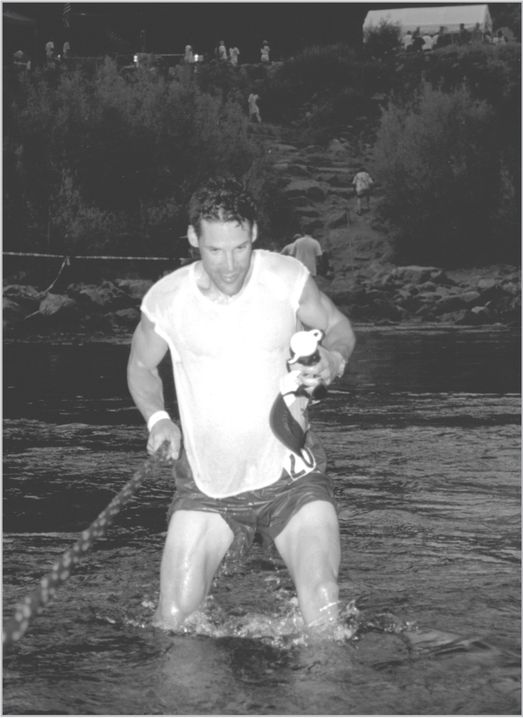

The dark, icy-cold river came up over my waist as I struggled across, trying not to slip on the rocky bottom and get swept downstream. Through the turbulence, I carefully plodded, step by awkward step, clumsily fighting to remain balanced and upright in the swift current. As I reached the distant shore, drenched from my chest down, I found that a rope had been attached to a tree on the hillside above. I used it to hoist myself wearily up the muddy embankment.

On the far side of the river crossing was an aid station staffed with students and professors from the University of California School of Podiatry. Many of the athletes were in dire need of foot repair by this point. I sat in a rickety lounge chair, and a podiatry student immediately knelt in front of me.

“I think there's a clam shell or something in my left shoe,” I told him.

He removed my shoe and sock and shook a lot of sand and small rocks out, but no clam shell. Reaching inside the sock, he pulled something out and flashed his penlight on it.

“Is it a shell?” I asked.

“Uh, no.” He held the object up. “That,” he grinned, “would be your big toenail.”

I was mortified, then amused.

How could I lose a toenail without knowing?

How could I lose a toenail without knowing?

“It's okay,” I said to him calmly. “I wasn't that attached to it anyway.”

He laughed and asked if he could keep it. I guess that's the kind of trophy a podiatry student keeps around the dorm.

We decided not to mess a whole lot with my feet. There wasn't much that could be done, really. From this point forward, it was principally a matter of damage control.

The Rucky Chucky River Crossing

Darkness had taken over, so I strapped on a headlamp and switched on my handheld flashlight. Twenty-two miles separated me from the finish line. I had successfully navigated the high water; now would come the hell.

The Rucky Chucky River Crossing to Auburn Lakes Trail Miles 78 to 85.2People say

the real race begins after crossing the river. My watch read 9:51 P.M., which was, miraculously, a full hour ahead of a projected twenty-four-hour finishing pace. As I started down the trail, a man recording checkout times enthusiastically informed me that I was in 20th place.

the real race begins after crossing the river. My watch read 9:51 P.M., which was, miraculously, a full hour ahead of a projected twenty-four-hour finishing pace. As I started down the trail, a man recording checkout times enthusiastically informed me that I was in 20th place.

“Geez,” I said with some surprise, “I'm just happy to be alive.”

It's hard to judge distances when running at night, especially on narrow trails. Your world is confined to the reach of your flashlight beam, and beyond that is just darkness. Detecting the contour of the terrain becomes impossible at times, and you're left running on little more than instinct. The climb from the river stretched out for 2 miles, and then the trail became a narrow tunnel through tall, heavy brush that smelt of dampness and earth. The brush was so overgrown that I often hacked along with my arms. Through the constant buzzing of crickets and croaking frogs, I'd periodically hear louder noises crashing through the brush and hope it was just a deer and not a cougar or bear.

Running with just the power of my headlamp and flashlight, I was again feeling very isolated. Mostly I liked the solitude of long-distance trail running, but in this weakened state I longed for the camaraderie of another runner. There were no other athletes in sight, no checkpoints, not even a jet in the sky. Was I still on the right trail? Not only was my body on the brink of collapse, I was now becoming apprehensive, seriously questioning what the hell I was doing out here. There was something deep and primitive about the experience, no doubt, but right now I didn't want an encounter that meaningful. Enough punishment already . . . Uncle! I longed to be sitting at home in my easy chair, beer in one hand and remote in the other, surfing mindlessly through repeats of

Seinfeld

and

Baywatch.

Seinfeld

and

Baywatch.

And then, to make matters worse, both my headlight and flashlight dimmed unaccountably. I carried extra batteries in my pack, so I stopped and changed them. But the lights for some reason remained dim. Could the new batteries be just as weak? Or was it the bulbs?

There was nothing to do but keep running. The trail before me was almost completely black. Branches and tree limbs appeared to jump out at me from nowhere. I could now barely detect the tip of my outstretched hand. And then, strangely, I began seeing outlines of green around everything, as though I were looking through night-vision goggles. The trail and foliage around me started to glow like a film negative. What was going on?

I looked up at the sky. There were no stars to be seen. No Milky Way, no Big Dipper. It was a cloudless night in the mountainsâthere should be a thousand twinkling stars. Yet all I saw was darkness.

That's when I knew I was going blind.

It's called nyctalopia, or night blindness. It can be caused by lowered blood pressure or exposure to bright light during the day. The body's capacity to produce a chemical compound called rhodopsin, or visual purple, which is necessary for the perception of objects in dim light, is temporarily impaired.

The blisters had been uncomfortable, the muscle spasms agonizing, but going blind really presented an obstacle. I could only see a foot or two in front of me. I walked very slowly with my flashlight held out in front. The Auburn Lakes aid station at mile 85 was relatively close, and voices, or music, resonated off in the distance. Even while I plodded along at this painfully slow rate, my muscles and joints radiated pain every time my foot hit the ground. I found myself pausing slightly after each step, and it took tremendous concentration to move forward in a straight line without wavering back and forth across the trail. Finally I decided to just sit down and gather myself. Moving at a snail's pace was demoralizing.

Sitting on the trailside, I had a sickening sense that my journey had come to an abrupt end. I was bruised and bloodied and in no shape to contend with the beating for another sixteen miles to the finish line. Plus, I couldn't see. Maybe I should just be thankful to have made it this far. I'd covered nearly 85 miles along one of the most extreme trails in the world, displaying strength and resolve along the way, breaking through one barrier after the next, a respectable accomplishment. Still, I wasn't satisfied.

Most dreams die a slow death. They're conceived in a moment of passion, with the prospect of endless possibility, but often languish and are not pursued with the same heartfelt intensity as when first born. Slowly, subtly, a dream becomes elusive and ephemeral. People who've let their own dreams die become pessimists and cynics. They feel that the time and devotion spent on chasing their dreams were wasted. The emotional scars last forever. “It can't be done,” they'll say, when you describe your dream. “It'll never happen.”

My dream was dying. I didn't want to give up, but I seemed powerless to do anything about it. My decision was to wait for the next runner and ask him to send back help from the Auburn Lakes aid station, which was probably less than a mile ahead. I lay down in the dirt to waitâand promptly nodded off.

I awoke in confusion, not being able to place my whereabouts for a second. I could only have dozed for a few minutes, but it must have been a very deep slumber and it left me in a daze. When I finally gathered my senses, I recognized something odd and beautiful: the sky was again filled with shining stars. My vision had partially come back.

Suddenly I was infused with a renewed sense of hope. If I could see, I could move forward, and if I could move forward, I could continue chasing my dream. It might be slow going, but it certainly beat being carried out on a stretcher.

I sat up and turned on my flashlight and headlamp. The light they put out appeared weak and diffused, but it would do. It would have to do; I wasn't stopping.

The first few steps were like running on legs of marble. Pain shot from my foot to my pelvis like lightning bolts. Limping onward, I could now clearly hear rock music nearby. The checkpoint had to be within half a mile.

Then my eyesight began dimming again; the miraculous reprieve had been short-lived.

The aid station was so close that I could now detect lyrics to the songs and clearly hear laughter echoing off the hills. I marched blindly onward. Then there were lights, but they cast a weird rainbow glow, perhaps some new effect of the night blindness. I shook my head to clear my vision, but the colors remained steadfast.

I plodded toward them . . . and discovered that the colors were real. Someone had strung hundreds of Christmas lights throughout the forest. Just to screw with me, I'm sure.

At the station I was guided into a chair. People were asking me questions. The music was a Stones song:

“When the whip comes downnn . . . yeah, when the whip comes down! ”

Another fitting choice for the day's sound track. More questions were thrown at me out of the shadows.

“When the whip comes downnn . . . yeah, when the whip comes down! ”

Another fitting choice for the day's sound track. More questions were thrown at me out of the shadows.

“I'm all right, I suppose,” I managed to tell them. “But I kind of had a meltdown a few miles back. I'm having a hard time seeing.”

“Oh, that's okay,” came an enthusiastic reply. “We can fix that . . . Hey, Bob, bring over that yellow tackle box with all the batteries in it. This guy's flashlight is going dead.”

“No,” I said. “It's not the batteries.”

“That's okay, too,” he chirped. “We got extra bulbs as well.”

“It's not the batteries or the bulbs . . . it's me. Something's going wrong with my vision.”

There were several gasps in the crowd, and the guy helping me sputtered, “Oh, Jesus!”

Now there was a buzz of people all around me. They turned down the music, and I could hear lots of whispering. Someone moved behind my chair and began massaging my shoulders and neck.

“You still look pretty good,” that person said. “It's too bad about your eyes.”

There was some rustling and footsteps, and one of the other volunteers spoke. He cleared his voice a couple of times like the beginning of a town hall meeting.

“Okay, here's what we're going to do. We'll set you up on one of the cots and get you comfortable so you can sleep. Then in the morning, we'll get you out on horseback . . . how does that sound?”

“Well . . . ,” I said, hesitantly. “It sounds pretty good. Except for one minor detailâI'm going to keep running.”

A murmur buzzed through the crowd.

“But how you going to do that?” someone asked.

“You can't see.”

“Good question,” I replied. “But I can't be concerned with details at this point.”

It was a joke, but no one seemed to find it funny.

Somebody brought over a plate of brownies. Biting into one, I discovered that they were laced with espresso beans.

“Wow,” I said, grinning. “That's definitely going to put some life back in me.”

The small crowd got a kick out of my attempt at humor, but I think they were mostly laughing at the mess I was making with the brownies.

In a few minutes, the effects of the caffeine and sugar took hold. The jolt hit me like a mild electrical shock. I'd never eaten whole espresso beans before, and the experience was marvelous. Almost instantaneously I was wired.

Oddly, the lift helped my vision, and I could now distinctly make out the individual colors of each light.

Why Christmas lights?

I wondered. This whole scene was very bizarre, almost like I'd entered an

Alice in Wonderland

story. Perhaps there was more in those brownies than just caffeine. Or perhaps the nineteen hours of continuous running had altered my brain chemistry in some unusual way. Whatever might be going on, the net effect was vitalizing; my senses were firing.

Why Christmas lights?

I wondered. This whole scene was very bizarre, almost like I'd entered an

Alice in Wonderland

story. Perhaps there was more in those brownies than just caffeine. Or perhaps the nineteen hours of continuous running had altered my brain chemistry in some unusual way. Whatever might be going on, the net effect was vitalizing; my senses were firing.

As I wolfed down another brownie in preparation for departure, someone asked, “Are you sure you know what you're doing?”

“No,” I replied. “I have absolutely no idea what I'm doing. In fact, I'm not even sure where I'm at right now.”

That drew plenty of laughs, but it wasn't intended as a joke. I really had no idea what I was doing; this was entirely uncharted territory for me. At least I now had

hope,

which is more than what I'd had an hour ago.

hope,

which is more than what I'd had an hour ago.

“You've got balls, buddy,” a volunteer said as I headed off into the night. “Good luck.”

Chapter 10

Forever

Changed

Changed

Bid me run, and I will strive with

things impossible.

things impossible.

âShakespeare,

Julius Caesar

Auburn Lakes to Robie Point Midnight, June 26, 1994Julius Caesar

The trail weaved back

into thick foliage, with rocks and branches strewn across the path, but the lift from those magic brownies carried me along pleasantly. My step was more nimble and lighter than it had been. Clearly I was tapping into a reserve that I might not have adequate capital to cover in the not-too-distant future. Surely it wasn't normal to feel so energetic 87 miles into a run. This had to be deficit spending.

into thick foliage, with rocks and branches strewn across the path, but the lift from those magic brownies carried me along pleasantly. My step was more nimble and lighter than it had been. Clearly I was tapping into a reserve that I might not have adequate capital to cover in the not-too-distant future. Surely it wasn't normal to feel so energetic 87 miles into a run. This had to be deficit spending.

Other books

The Absent Author by Ron Roy

Stronger by Jeff Bauman

You Can't Get Lost in Cape Town by Zoë Wicomb

Shadow of a Tiger by Michael Collins

Untamed (Vampire Awakenings, Book 3) by Brenda K. Davies

Leslie LaFoy by Jacksons Way

Operation: Midnight Rendezvous by Linda Castillo

Soft Target by Hunter, Stephen

Disturbing the Dead by Sandra Parshall

Raiding With Morgan by Jim R. Woolard