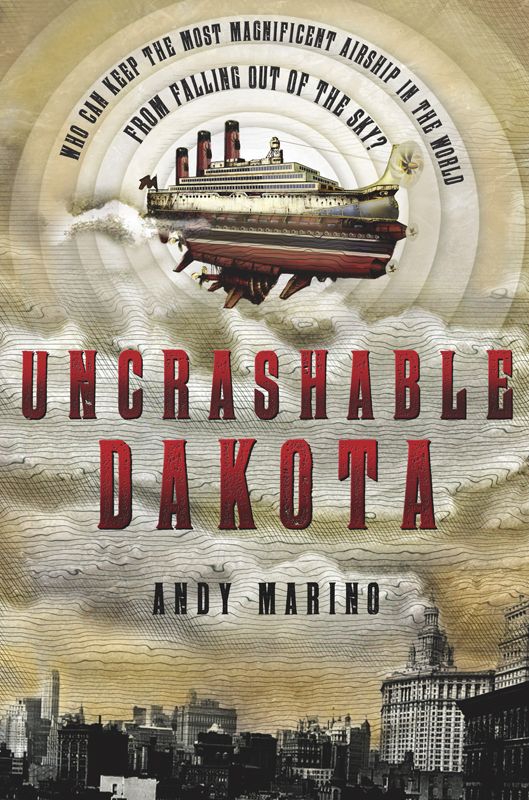

Uncrashable Dakota

Read Uncrashable Dakota Online

Authors: Andy Marino

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

CONTENTS

The History of Flight in America: Part One

The History of Flight in America: Part Two

The History of Flight in America: Part Three

The History of Flight in America: Part Four

The History of Flight in America: Part Five

The History of Flight in America: Part Six

PROLOGUE

1909

HOLLIS DAKOTA

was ten years old when his parents took him to the shipyard that sprawled like a spilled bucket of ash across the river from New York City. His family owned the shipyard, but Hollis had never been there, because he lived in the sky.

The Dakota family business was airships. The yard was their clattering, smoky birthplace. Hollis had seen it from above: a gated compound the size of a city, gridded with factories and littered with the skeletal husks of unfinished ships. He pictured it this way, spread out in his mind like a full-color map, as he followed his parents along a wide gravel road between two hangars. The sulfurous smoke that hung about the yard slithered into his nose. His eyes began to water. He stumbled dizzily behind his parents with rubbery legs and hesitant steps.

He was getting groundsick.

“Whoa!” his father said after a while, as if Hollis and his mother were horses. They stopped walking. They were somewhere in the center of the yard, past the hangars, standing in a vast expanse of packed dirt. Hollis didn’t know why they were here. The whole trip had the winking, secretive air of Christmas morning. His father cleared his throat with a phlegmy rasp and swallowed with a pained grimace.

“You are free to spit in front of me if you must, Wendell,” his mother said. “I’ve seen worse.”

“That was more dust than spit, I’m afraid.” His father used the tip of his finger to balance loose, smudgy spectacles on the bridge of his nose. “Well. Here we are.”

Hollis rubbed the grit from his eyes, and the hazy confusion of his surroundings sharpened into a magnificent scene. He had been led into the heart of a grand excavation: the remains of some prehistoric monster whose rib cage alone would dwarf a whale. Unearthed silver bones curved up to challenge the tall buildings of Manhattan rising out of the fog to the east.

“You see,” his father said, “I want you both to experience firsthand the not-so-humble origins of what will one day be the flagship of the Dakota Aeronautics fleet.”

Not monster bones

, Hollis thought. The steel frame of a new airship big enough to carry a Hawaiian island in its belly. He tried not to look disappointed that he wasn’t touring a city-sized fossil.

“Hot rivet!”

Hollis tracked the insistent shout to a scaffold embracing the nearest steel rib. Fifty feet above the ground, a man flung a tiny piece of metal from a steaming brazier. There was an arcing flash, and his partner caught it in a wooden bowl. In a single practiced motion, he extracted it with a pair of tongs, held it against the framework, and answered with a “

hot riv-ETT

” of his own. Two diminutive figures bearing mallets emerged from a shadowy part of the scaffold, and a quick, brutal bashing took place to drive the rivet in.

“What you’re witnessing up there is the hull in its infancy,” his father said.

Hollis was entranced by the loose-limbed courage of the workers. In less than a minute, they secured four rivets. Their voices rang out in a call-and-answer that harmonized with others up and down the row. Some of the voices sounded like they belonged to women.

Not women

, he realized, squinting.

Children.

“She’s going to be a real cloud splitter,” his father said. “The perfect combination of luxury and practicality, relaxation and exploration, comfort and luxury. Brought to life by all this productive sweat you can feel in the air.”

Hollis tried to detect moisture.

“I’m just not sure it’s going to be

big

enough, dear,” his mother said.

His father failed to catch the gentle sarcasm. He unclasped his hands from behind his back and stretched them out straight to either side.

“Darling, I assure you, you’re standing inside the framework of the world’s first metropolis in the sky, with all the familiar diversions and entertainments of Manhattan and space to accommodate enough passengers to rival the population of a modest northeastern town. And the first airship to be positively”—he paused to nod at a gang of passing workmen shouldering long wooden boards, then lowered his voice to a whisper—“

uncrashable.

”

His mother snorted a single quick

hmmph

. “Uncrashable?” She shook her head. “That’s a bit cavalier, don’t you think?”

“But, Lucy, you have to remember…,” his father said, trailing off before he could tell her what it was she had to remember. Hollis considered the word

cavalier.

It conjured images of charging cavalry horses and puffs of pistol smoke.

“Don’t you

but, Lucy

, me,” she said. “You know as well as I do where that kind of headstrong attitude landed your father.”

“My father never landed anywhere.”

She put her hands on her hips. “Exactly.”

1

ON A CLEAR,

bright morning in April of 1912, Hollis helped his mother cut the ribbon that hung across the first-class entrance to the

Wendell Dakota.

It was a two-person job, because the scissors, like the airship, were enormous. One of the silver blades caught the sun and beamed it across the faces of the crowd gathered at the Newark Sky-dock; everybody blinked at once. The blades snapped together. There was a momentary hush as the halves of the ribbon whipped and fluttered in the wind. Then the crowd erupted into cheers. Tall black hats tumbled up into the air along with short-brimmed bowlers and floppy caps.

A pair of earnest young crewmen hopped up on the platform with Hollis and his mother. They took the giant scissors and disappeared, leaving the two Dakotas to wave and grin and bask in the hoots and hollers of the exhilarated crowd. Hollis felt a gentle hand on his shoulder and glanced up at his mother. Without unfreezing her smile, she fanned her face with a few up-and-down waves of her hand and rolled her eyes. Hollis gave a quick nod in agreement. He was sweating right through the fabric of his custom-tailored suit, giving some of the richest people in the world—not to mention their servants, biographers, music instructors, translators, masseuses, and governesses—a fine view of the spreading stains that had already claimed his armpits. And he thought it must be ten times worse for his mother, who was wearing a complicated dress topped with a lace collar that crept up her neck and presented her head to the world like a blossoming rose.

Hollis let his gaze drift across the jostling landscape of passengers waiting to board, their faces flushed and shiny in the heat. Uniformed stewards assigned to each prominent family were scattered about to ensure that no first-class feathers were ruffled by line-cutting or a lack of decorum. Red-capped porters dotted the crowd like cherries on a rich dessert. As high as the roof of a midtown office building, the top of the sky-dock was the first-class rallying point, where the wide gangway transferred passengers to their expansive staterooms in the upper third of the airship. Below them, second-class travelers looked forward to their own well-appointed rooms, while third class would make for shared bunks (men to starboard, women to port). At the bottom of the towering sky-dock, steerage passengers were bound for the holds that surrounded the coal bunkers and boiler rooms.

“I suppose I’ll take a hot day over a stormy one,” Hollis’s mother said, blowing a kiss to some ancient specimen whose pince-nez flashed as he bowed.

“I have to get out of this suit,” Hollis said, resisting the urge to loosen his tie. Using his hand to block the sun, he observed the far edge of the platform where the last passengers were gathered. Beyond them, the blue sky hung empty, and he imagined the clouds had been driven away at his father’s command.

* * *

BESIDES THE CREW MEMBERS

readying the ship for launch, Hollis was the first person to climb aboard. It was part of his belated birthday present: he’d turned thirteen last month. He clanked up the ramp from the snipped ribbon to the first-class promenade deck in heavy, steel-lined boots. Every passenger wore them for boarding a Dakota Aeronautics ship so as not to get blown out into the sky by a vicious gust of high-altitude wind. Accidents happened, but the boots kept the blow-away rate to a minimum.

Hollis was greeted at the top of the ramp by Marius Rogers, one of the laborers at the fringes of any given airship’s crew—assisting the chief second-class purser, performing minor plumbing repairs, helping the ship’s librarian stay organized. The joke was that Marius had a secret twin; he always seemed to be in two places at once.

“Morning, Mr. Dakota.” Marius tipped a nonexistent cap by tugging on a lock of his hair. Hollis held out his hand, and they shook. Marius made a face. “You stick that in water?”

“It’s hot out.”

“Oh, come on, now. We’re in New Jersey, not New Guinea. And it’s not even summer.” He dropped Hollis’s hand with exaggerated disgust. Then he stood a little straighter and added a crisp, “Sir.”

“Not you, too,” Hollis said. Lately, crewmen had begun to treat him with an alarming level of professional respect. “Marius, you don’t have to

sir

me.”

“Better get used to it.”

“Don’t—”

“Sir.”

Hollis sighed. “When did you slink aboard, anyway?”

“Been here three days.”

“Shoveling coal?”

Marius laughed. “I doubt the stokers want me anywhere near a furnace.”

Hollis eyed the screw top of a hip flask peeking out of the crewman’s uniform pocket. “I’m glad you caught this assignment.”

“Honest truth, I would’ve booked passage anyway, just for the ride.”

“Maybe next time you’ll get to,” Hollis said. Marius smiled weakly. Concerned that the man had taken this as a threat to his job, Hollis pointed at the screw top. “I don’t care about that.”

Marius shifted his weight, and the flask dropped out of sight. “You know, Mr. Dakota,” he said, “I never seen anything like this ship. Every hair in place. They could load the passengers, give it a shove, and let it fly itself across the Atlantic.”

“It would have to be a pretty big shove.”

Hollis stepped out onto the flat expanse of the first-class promenade deck. The fresh-cut pine planks had been sanded, waxed, and buffed to a glossy sheen. Straight ahead, the overhang of the topmost recreational area—the sundeck (steel-lined boots required at all times)—sheltered fifty reclining chairs bolted down in a perfect row. In the enticing shade behind them, a hundred round black stools squatted next to a mahogany bar as long as a city block. Unopened bottles of clear and amber liquor, including his grandfather Samuel Dakota’s patented Moonshine Whiskey, were stocked ten feet high along the back of the bar, the small print of their labels reflected in gilded mirrors. Bright little dots of light slid up and down the bottles in time with the gentle bobbing of the docked airship.