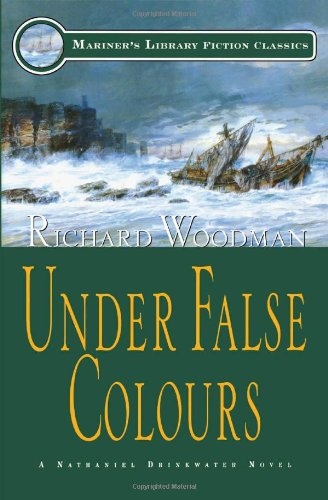

Under False Colours

Read Under False Colours Online

Authors: Richard Woodman

Tags: #Fiction, #Historical, #Sea Stories, #War & Military

Table of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Contents

- Maps

- PART ONE The Baiting of the Eagle

- CHAPTER 1 Upon a Secret Service

- CHAPTER 2 Baiting the Eagle

- CHAPTER 3 The Jew

- CHAPTER 4 The Gun-brig

- CHAPTER 5 The Storm

- CHAPTER 6 Coals to Newcastle

- CHAPTER 7 Helgoland

- PART TWO The Luring of the Eagle

- CHAPTER 8 The Lure

- CHAPTER 9 Santa Claus

- CHAPTER 10 Hamburg

- CHAPTER 11 Sugar

- CHAPTER 12 The Iron Marshal

- CHAPTER 13 The Firing Party

- CHAPTER 14 Altona

- PART THREE The Snaring of the Eagle

- CHAPTER 15 Beauté du Diable

- CHAPTER 16 The Burial Party

- CHAPTER 17 Ice

- CHAPTER 18 The Scharhorn

- CHAPTER 19 Refuge, Rescue and Retribution

- CHAPTER 20 Outrageous Fortune

- Author's Note

For my father, who first mentioned the Northampton boots.

PART ONE

PART ONEThe Baiting of the Eagle

CHAPTER 1'The British Islands are declared to be in a state of blockade.

All commerce and all correspondence with the British Isles are prohibited.

Every . . . English subject . . . found in countries occupied by our troops . . . shall be made prisoners of war.

The trade in English commodities is prohibited

NapoleonArticles 1,2,4 and 6, The Berlin Decree, 21 November 1806

Upon a Secret Service

August 1809

'God's bones!'

Nathaniel Drinkwater swallowed the watered gin with a shudder of revulsion. His disgust was not entirely attributable to the loathsome drink: it had become his sole consolation in the weary week he had just passed. Apart from making the water palatable the gin was intended as an anodyne, pressed into service to combat the black depression of his spirits, but instead of soothing, it had had the effect of rousing a maddeningly futile anger.

He pressed his face against the begrimed glass of the window, deriving a small comfort from its coolness on his flushed forehead and unshaven cheek. The first floor window commanded a view of the filthy alley below. From the grey overcast sky — but making no impression upon the dirty glass — a slanting rain drove down, turning the unpaved ginnel into a quagmire of runnels and slime which gave off a foul stench. Opposite, across the narrow gutway between the smoke-blackened brick walls, a pie shop confronted him.

'God's bones,' Drinkwater swore again. Never in all his long years of sea service had an attack of the megrims afflicted him so damnably; but never before had he been so idle, waiting, as he was, above a ship's chandler's store in an obscure and foetid alley off Wapping's Ratcliffe Highway.

Waiting ...

And constantly nagging away at the back of his mind was the knowledge that he had so little time, that the summer was nearly past, had

already

passed, judging by the wind that drove the sleet and smoke back down the chimney pots of the surrounding huddled buildings.

Yet still he was compelled to wait, a God-forsaken week of it now, stuck in this squalid room with its spartan truckle bed and soiled, damp linen. He glared angrily round the place. A few days, he had been told, at the most ... He had been gulled, by God!

He had brought only a single change of small clothes, stuffed into a borrowed valise with his shaving tackle; and that was not all that was borrowed. There were the boots and his coat, a plain, dark grey broadcloth. He had refused the proffered hat. He was damned if he would be seen dead in a beaver!

'You should cut your hair, Drinkwater, the queue is no longer

de rigueur

.'

He had avoided

that

humiliation, at least.

He turned from the window and sat down, both elbows on the none-too-clean deal table. Before him, beside the jug and tumbler of watered gin, lay a heavy pistol. Staring at the cold gleam of its double barrels he reflected that he could be out of this mess in an instant, for the thing was primed and loaded. He shied bitterly away from the thought. He had traversed that bleak road once before. He would have to endure the gristle-filled pies, the cheap gin and the choked privy until he had done his duty. He swung back to the window.

The rain had almost emptied the alley. He watched an old woman, a pure-finder, her head covered by a shawl, her black skirt dragging on the ground where amid the slime, she sought dog turds to fill the sack she bore. Two urchins ran past her, throwing a ball playfully between them, apparently oblivious of the rain. Drinkwater was not deceived; he had observed the ruse many times in the past week. He could see their victim now, a plainly dressed man with obvious pretensions to gentility, picking his way with the delicacy of the unfamiliar, and searching the signs that jutted out from the adjacent walls. He might be something to do with the shipping lying in the Thames, Drinkwater mused, for his like did not patronize the establishment next door until after dark. He was certainly not the man for whom Drinkwater was waiting.

'You'll recognize him well enough,' Lord Dungarth had said, 'he has the look of a pugilist, a tall man, dark and well set up, though his larboard lug is a trifle curled.'

There had been some odd coves in the alley below, but no one to answer that description.

Drinkwater watched the two boys jostle the stranger from opposite sides, saw one pocket the ball and thumb his nose, saw the stranger raise his cane, and watched as the second boy drew out the man's handkerchief with consummate skill, so that the white flutter of its purloining was so sudden and so swift that it had vanished almost before the senses had registered the act. The two petty felons, their snot-hauling successful, capered away with a gleeful dido, the proceeds of their robbery sufficient to buy them a beef pie or a jigger of gin. The stranger stared after them, tapped his wallet and looked relieved. As the man cast a glance back at the trade signs, Drinkwater withdrew his face. A moment later the bell on the ship's chandler's door jangled and the stranger was lost to view. In the narrow ginnel a vicious squall lashed the scavenging pure-finder, finally driving her into shelter.

Drinkwater tossed off the last of the gin and water, shuddered again and contemplated the pistol. He picked it up, his thumb drawing back each of the two hammers to half cock. The click echoed in the bare room, a small but deliberately malevolent sound. He swung the barrels round towards him and stared at the twin muzzles. The dark orifices seemed like close-set and accusing eyes. His hand shook and the heavy, blued steel jarred against his lower teeth. He jerked his thumb, drawing back the right hammer to full cock. Its frizzen lifted in mechanical response. It would be so easy, so very easy, a gentle squeezing of the trigger, perhaps a momentary sensation, then the repose of eternal oblivion.

He sat thus for a long time. His hand no longer shook and the twin muzzles warmed in his breath. He could taste the vestiges of gunpowder on his tongue. But he did not squeeze the trigger, and would ever afterwards debate with himself if it was cowardice or courage that made him desist, for he had become a man who could not live with himself.

In the months since the terrible events in the rain forest of Borneo, his duty had kept him busy. The passage home from Penang had been happily uneventful, blessed with fair winds and something of a sense of purpose, for Lord Dungarth had written especially to Admiral Pellew — then commanding the East Indies station — that Captain Drinkwater and his frigate were to be sent home the moment they made their appearance in the China Sea. The importance of such an instruction seemed impressive at a distance. His Britannic Majesty's frigate

Patrician

had arrived at Plymouth ten days earlier and Drinkwater had been met with an order to turn his ship over to a stranger and come ashore at once. Taking post, he had reported to the Admiralty. Lord Dungarth, head of the Secret Department, had not been available and Drinkwater's reception had been disappointingly frosty. The urgency and importance with which his imagination had invested his return to England proved mistaken. Captain Drinkwater's report and books were received, he was given receipts and told to wait upon their Lordships 'on a more convenient occasion'.

Angry and dejected he had walked to Lord North Street to remonstrate with Dungarth. He had long ago angered the authorities — in the person of John Barrow, the powerful Second Secretary — but had hoped that his destruction of the Russian line-of-battle ship

Suvorov

with a mere frigate would have mollified his detractor. Apparently he remained in bad odour.

There had been more to fuel Captain Drinkwater's ire than official disapprobation. In a sense he had been relieved to have been summoned so peremptorily to London. He did not want to go home to Petersfield, though he was longing to see his children and to hold his wife Elizabeth in his arms again. To go home meant confronting Susan Tregembo, and admitting to her the awful fact that in the distant jungle of Borneo he had been compelled to dispatch his loyal coxswain Tregembo, whose tortured body had been past all aid, with the very pistol that he now held. The fact that the killing of the old Cornishman had been an act of mercy brought no relief to Drinkwater's tormented spirit. He remained inconsolable, aware that the event would haunt him to his own death, and that in the meantime he could not burden his wife with either himself or his confession. (See

A Private Revenge

)

In such a state of turmoil and self-loathing, Drinkwater had arrived at Lord Dungarth's London house. A servant had shown him into a room he remembered, a room adorned with Romney's full length portrait of Dungarth's long-dead countess. The image of the beautiful young woman's cool gaze seemed full of omniscient accusation and he turned sharply away.

'Nathaniel, my dear fellow, a delight, a delight ...'

His obsessive preoccupation had been interrupted by the entry of Lord Dungarth. Drinkwater had thought himself ready for the altered appearance of his lordship, for Admiral Pellew, sending him home from Penang, had told him Dungarth had lost a leg after an attempt had been made to assassinate him. But Dungarth had been changed by more than the loss of a limb. He swung into the room through the double doors on a crutch and peg-leg, monstrously fat, his head wigless and almost bald. The few wisps of hair remaining to him conferred an unkempt air, emphasized by the disarray and untidiness of his dress. Caught unprepared, shock was evident on Drinkwater's face.

'I know, I know,' Dungarth said wearily, lowering himself into a winged armchair, 'I am an unprepossessing hulk, damn it, a dropsical pilgarlic of a cove; my only consolation that obesity is considered by the

ton

a most distinguished accomplishment.'