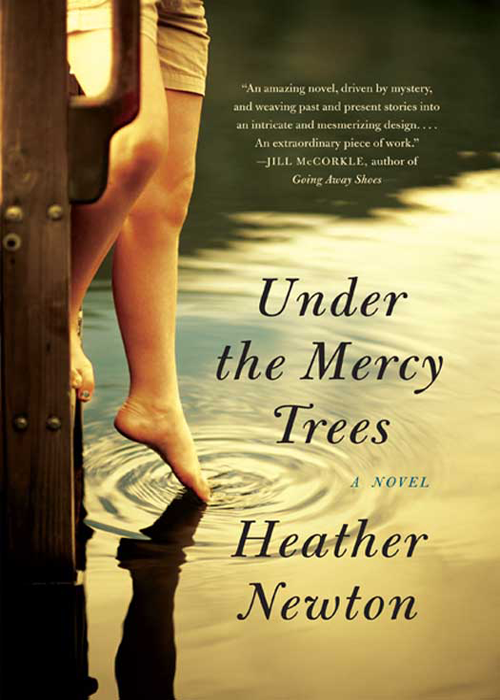

Under the Mercy Trees

Read Under the Mercy Trees Online

Authors: Heather Newton

Under the Mercy Trees

A Novel

Heather Newton

Dedication

For my redheads, Michael and Madeleine

Contents

October 14, 1986

December 10, 1986

Society Page, January 7, 1987

April 9, 1987

That last night at Rendezvous Falls, the Ford Sunliner seemed to drive itself, the engine so powerful it felt as if some force were pulling them up the mountain. Martin drove one-handed, vibration from the steering column numbing his palm. Beside him in the passenger seat Liza clutched his other hand, her grip folding bone. The moon lit up fields on either side. The car entered woods and climbed north, its headlights sweeping the curvy road. Liza pressed a fist against her mouth and began to cry.

They rounded a bend and the waterfall loomed up, higher than a four-story building, its roaring water spitting white in the moonlight. Martin pulled over to the side of the road and went around to Liza's door to help her out. The air was cooler here than in town, and the water misting over them from the falls made Liza shiver despite her sweater. He almost told her to get back in the car, but she stepped past him and headed up the narrow path that led to the top of the falls. Martin reached in the glove compartment for a flashlight, then followed her. Rhododendron and holly branches slapped his body. Here and there bear scat dotted the path. Liza climbed on, her slender shoulders hunched, ponytail bobbing. Martin stumbled once or twice on tree roots before they came out onto the curving rock face just above the falls.

Liza stopped and breathed in the moist air, her shoulder blades rising and falling. Moon bled silver over the rock's smooth surface, illuminating ferns that claimed a toehold in tiny cracks and glistening streaks of wet where the falls had sprayed the gray-and-orange stone. She stepped farther out.

“Don't go too near the edge,” Martin said. The thunder of the falls drowned out his voice. He took her arm. “Let's go back.”

She pointed to a long crevice that ran from where they stood down to a shelf behind the curtain of solid water. The braver folk of Solace Fork used it to slide behind the falls. “Come with me,” she said.

“No, Liza.”

“Please.” The moonlight seemed to stretch her skin taut over her cheekbones. Her face was fierce with all that she wanted from him, all that he couldn't give her. She took the flashlight from his hand, then sat in the crevice and eased down on her seat, disappearing behind the white water.

Martin stood alone in the mist of the falls, unable to follow.

WILLOBY NEWS & RECORD

, October 14, 1986

The family of Leon Owenby, 65, has reported him missing from the home place, off Bryson City Road. Mr. Owenby's brother James Owenby saw him a week ago Tuesday when he went by to borrow a pair of tin snips, but nobody has seen him since. “It ain't like him to take off without telling somebody,” said Hodge Goforth, Willoby County's director of Emergency Services and a family friend. “You couldn't run him out of the county.”

Martin

Broken. His last scrap of dignity twisted off like a chicken wing. Martin Owenby climbed three flights to the Manhattan apartment he shared with Dennis on West Fifteenth Street, his heart fluttering idiotically in his chest. The battered leather strap of his suitcase threatened to give way as he bounced it up the steps. Nothing valuable left inside if it did spill. Air wheezed through his nose in an exotic bird call. Tiny bottles of Scotch from the plane rattled in his overcoat pocket.

On the landing, he stopped to get his breath, then unlocked the apartment door. Dennis was dozing on the sofa in his dressing gown, his antiques crowding around him. He waited up for entertainment, not out of concern. His corpulent body curled like a woman's. Martin and Dennis had been lovers once, until they both turned apologetically to younger men. Now they sniped at each other with the weapons of familiarity, like the worst of married couples.

Dennis blinked awake and saw Martin's slept-in clothes and the bruise smeared blue-yellow across his left cheek, smelled the scent of liquor spilled three days ago down his shirtfront. “He rolled you, did he?”

He. The blond midwestern god Martin took to St. Kitts ten days ago. “It was worth it,” he said, wishing it were true. Tickets charged above the limit on his sole unfrozen credit card. Past fifty, looks and wit were no longer legal tender, and sex was costly. In this era of AIDS Dennis seemed content to remain celibate. Martin was not.

Dennis sighed and heaved himself off the couch. “Your family's been calling. Your brother Leon has disappeared. It's been over a week since they noticed him missing.”

“Missing?” Martin pushed his suitcase through the doorway of his closet-size bedroom. His head was less than clear, his tongue like cotton.

“I would have called you, if you'd left me a number,” Dennis said.

“Maybe he decided to go somewhere.” Martin didn't believe the words. His oldest brother, so like their father, not a spontaneous freckle on his body. Up at five every day, peed off the porch, lit his stove. Made black coffee and cornbread. Fed the leftovers to the dogs, God forbid he should buy dog food. Splashed water on his face and combed what was left of his hair. Rinsed his mouth out and spit. Did his chores. Walked his property. Smoked a slow cigar. Martin stayed in touch with his other siblings, putting in just enough effort to keep them from writing him off. The women still babied him, his sisters and sister-in-law, and he even considered his brother James a friend. But not Leon.

“James said they found his truck at the house. But his wallet was gone,” Dennis said.

“Do they expect me to come home?” Martin knew the answer. He looked at his watch. It was too late to call his family. James would be asleep with his hearing aid out, and it would be Bertie, James's wife, who would be frightened awake. Martin could imagine her lying rigid in the bed, her prematurely white hair puffing around her head like a Q-tip, listening to the phone ring, expecting the worst.

“It's a family emergency. And your friend Liza is prepared to meet you at the airport.” Dennis picked up a message from the telephone table and dangled it over Martin's head.

Dennis was jealous of Liza, or rather, the myth of Liza that Martin perpetuated. Her picture, dropped artfully from his billfold for years to reassure employers and others of his heterosexuality. His girlfriend. His long-lost love. His brother Leon snapped the photo at Martin's high school graduation, when Liza reached slender-necked to kiss Martin's cheek. It had grown as frayed and dated as the lies Martin told. He kept the photo hidden now, tucked behind his maxed-out credit cards, but it still made him feel handsome and romantic to have once had this girl love him so.

He snatched the message from Dennis and started to call the airline, then remembered he was out of cash and credit and put down the receiver. “Can you lend me some money?”

“Oh, for God's sake.”

“I'll pay you back. I'm expecting a check for that computer manual I edited.”

Dennis snorted. “I'll lend you the money but only for your family's sake. Put the plane ticket on my credit card, and I'll get you some cash tomorrow.” He moved sideways between furniture to reach his wallet on an end table and handed Martin his Visa card.

Martin booked a flight for the day after next, giving himself time for the bruise on his face to heal, then dialed Liza's number. It was late, but her voice when she answered was clear, not graveled by sleep. At the sound of it he felt tears press against the back of his eyes and turned toward the wall so Dennis wouldn't see.

“Hey,” he said.

“Hey, yourself.” Her voice was young. She was still the auburn-haired beauty he had left in Willoby County more than thirty years ago. He gave her his flight number and arrival time.

“I'll be there.”

He imagined her standing in the dim light of her kitchen. The last time he'd gone back to Solace Fork, a few years ago, she had cut her hair short, but her skin was as smooth and unlined as ever, her body trim. Martin wanted to reach through the phone line, have it take him back to when they were children. Liza was silent, and for a moment he thought he had lost the call. “Liza?”

“Yes?”

“Never mind.”

“So I'll see you at the airport.”

“Put the top down for me,” he said, a reference to the baby blue convertible she drove when they were in high school, a lame joke to remind her who he was. They hung up.

“How sweet.” Spit glistened in the corners of Dennis's mouth. “The two of you communicate without words.”

Martin wanted to shut him up, but Dennis had just lent him money. Martin and Liza didn't need words because they invented in their minds the words they wished the other one would say. The image Liza had of him bore little resemblance to who he really was, but around her he was his best, most beautiful, and noble self. He was unbroken.

Liza

At the Owenby home place, carrying a cooler full of sandwiches as her excuse, Liza Barnard hiked up to where bloodhounds puzzled cold dirt and dozens of men raked a slow, ragged line over the property, their backs to her. Hodge Goforth, Willoby County's director of Emergency Services, walked in the center. There was a pleasing softness about Hodge, inside and out. When he and Liza and Martin Owenby were children, Hodge may have coveted Martin's hard muscle and sharp wit, but somewhere along the line Hodge had accepted himself. In front of Hodge, brush and trees thickened as the mountain sloped upward.

The men reached the boundary of the quadrant they had marked off and turned back toward Liza. Hodge saw her and waved. She put her cooler with a pile of food and equipment near the edge of the woods. Hodge left the line and came over to join her. Too many years of his wife's good cooking hung around his middle, and he wheezed like an old dog.

“How's it coming?” she said.

He shook his head, keeping his voice low. “We searched a week for the man. Now we're looking for a body.” Frost had covered fallen leaves the past few mornings.

“What do you think happened to him?” Liza said.

“No idea, but I don't have a good feeling about it.” Hodge pointed to Sheriff Wally Metcalf, who was walking their way, talking to his chief deputy. “Wally didn't want to treat it as a crime, but I talked him into it. Old people wander off all the time, but this is different. Leon wasn't confused, and he'd never leave his front door hanging open like that.” Over the ridge, Leon's house, just visible at the base of the mountain, looked ready to fall in.

“Did the sheriff find anything at the house?” Liza said.

“Nothing. He's told the family they can go back in.”

The sheriff spotted Hodge and Liza and headed toward them, grinning. “You distracting Hodge, Miz Barnard? He's getting behind.” After teaching English at the high school for nearly three decades, Liza was Miz Barnard to everyone.

“Sorry, Sheriff,” she said.

“I needed a break. I'm not as young as I used to be,” Hodge said.

“Uh-huh. But you're just as lazy,” Wally said.

Liza envied the easy friendship between Wally and Hodge. Hodge's office was in the same building as the Sheriff's Department. The two men saw each other every day. With all their history and Martin Owenby shared between them, Liza and Hodge still weren't completely at ease when they were alone together.

“This would be easier if all the Owenby men got along,” Hodge said. “We're having to keep them separated.”

At the far end of the line, Martin's older brother James poked through underbrush without lifting his head. Closer by paced Steven Owenby, the son of Martin's sister Ivy. Ivy had mental problems and hadn't been able to take care of her children, but Steven had turned out well, considering. The muscles in his jaw and back twisted with impatience, and grizzled hair stood out from his head, but Liza knew he wasn't as wild and scary as he looked. Steven was Martin's favorite nephew. Martin wasn't as fond of his other nephew, James and Bertie's son, Bobby.

“You're the only person I know who gets along with all of them,” Liza said.

“It's an odd spot to be in at times.” Hodge called over to Steven, “Steven, come here a minute.”

Steven walked over. “Hey, Miz Barnard.” He took out a cigarette and lit it.

Hodge wiped sweat off his forehead. “You got any thoughts on this, Steven? You know this property about as well as anybody.” Steven and his brother and sister had spent most of their young lives in foster homes, but in the summers Leon had Steven out to help him around the farm. Liza imagined a young Steven sleeping in the attic. The hundred-degree heat under the tin roof would have been stifling, but better than a bed in foster care.

Steven shook his head and exhaled smoke. “Leon wasn't afraid of the devil. He walked every inch of this property, in the light and the dark, at some point in his life.” He pulled something out of his pocket. “Look what I found yesterday, back in a cove where you'd swear nobody had trod since the Cherokee.”

They looked at what he held. It was the paper band off one of the cheap cigars Leon smoked, the words rubbed off by weather. Steven offered it to Wally Metcalf.

The sheriff shook his head. “He could be anywhere.”

Steven carefully put the band back in his pocket.

Wally said, “Steven, your uncle James told me the last time he saw Leon, your mother had just been by and left his clean laundry. Then when James went back a week later, there was almost no laundry in his dirty-clothes pile and the dogs hadn't been fed. I wondered if you might have seen Leon during that week sometime.”

“Naw.” Steven shook his head. “It's been at least a month since I seen him.”

Martin's brother James approached them, adjusting the hearing aid in his right ear so he could hear. He nodded to Liza, shy.

Wally pressed Steven. “You'd carry him around sometimes in that pickup truck of his, wouldn't you?”

Steven tossed down his cigarette and stubbed it out with his toe. “Everybody knows I'd drive him when he needed me to. What are you getting at?”

“Man wants to know if you drove Leon around any week before last,” James said quietly.

Steven turned toward James, hatred on his face. “If I'd've drove him, I would've said. What are you saying, James? That I'd hurt the only one of you that ever showed my family a kindness?”

“I'm not saying any such thing.”

Anger spurted out of Steven like water from a slit hose. “The rest of you treated my mama like dirt, like she embarrassed you. Well, you're the ones ought to be embarrassed. Walking into Solace Fork Baptist Church every Sunday of your lives like the saints of God or somebody, then letting us rot in foster care.” He spat on the ground. “If I was going to hurt somebody, James, you better believe it'd be you, not Leon.”

“Steven, come here a minute.” Hodge took Steven's arm and led him off a few yards, close enough for Liza and the others to eavesdrop. “Nobody's accusing you of anything, son. Wally has to ask questions. James has a right to hear what you know. That chip you carry around on your shoulder is going to get you in trouble.”

“That son of a bitch. That hearing aid makes him seem all harmless and innocent, but he ain't.”

“When's the last time you saw Leon?” Hodge said.

“A few weeks, like I said.” Steven turned around and raised his voice so they didn't have to strain to hear. “Leon didn't call me to drive him much anymore because he was getting James's boy, Bobby, to do it. Ask Bobby when he saw the man last.”

“I'll do that, son,” Wally said calmly.

Steven turned his back. “I'm out of here.”

“Steven, we still need you to help look,” Hodge said.

“Let James look for him his own damn self.” Steven shrugged off Hodge's hand. “No old man could last in the cold this long, not even Leon. Any more looking would just be for a family that never did a thing for me. I'll see you, Hodge.” He headed for the house, where the searchers' trucks were parked. Steven's hair was graying and his shoulders drawn up like an old man's, but to Liza's teacher eyes he was still a teenager with his feelings permanently hurt.

Wally called to Hodge. “He okay?”

“Yeah, he'll be all right.” Hodge walked over to James and slapped him on the back. “Let's get to it.”

“I'll head down and look by the sawmill,” James said.

Hodge waited for the sheriff and James to walk far enough away, then said to Liza, “It hurts me to see family at each other's throats like that. The Bible says, âfirst be reconciled to thy brother.' Seems like that ought to go for uncles and nephews, too.”

“Have you told them that?” she said.

Hodge shook his head. “I've learned to be sparing with Scripture around the Owenby men.” He looked at her. “You've spoken to Martin?”

“I'm picking him up at the airport tomorrow.”

“How'd he sound?”

“Hard to say.”

“It'll be good to see him.”

She nodded, not trusting her voice.

Hodge said good-bye and rejoined the search. The volunteers separated to cover the land that remained. Liza stood alone. She surveyed the expanse of land around them, exhausted fields and scraggly timber as far as she could see. A creek ran narrow through the Owenby property, past the house and down behind the old sawmill. She hoped, for the family's sake, that Leon wasn't lying out there somewhere. That he had gotten an urge to travel and climbed on a bus, off to see a lady friend no one knew he had. Around the property's edges, in the lace of bug-eaten leaves, the light was failing. She turned and went back to her truck.

With her headlights on she drove down the Owenbys' dirt road, then out onto paved state road. Her pickup truck hugged the same curves she and Martin had traveled in her Ford Sunliner convertible all through high school, before she knew Martin was gay, maybe before Martin himself knew he was gay. Deer eyes gleamed red in her headlights, and she clutched at time the way she grasped her steering wheel, her own selfishness appalling. Leon Owenby was missing, and Martin Owenby was coming home.

*Â Â *Â Â *

She was twelve. It was spring. Dandelion heads sloughed seeds like old men spitting teeth. Her father's mouth moved in a happy whistle, gusts of wind through the open windows snatching the sound. She trailed her hand out the window, blocking air with her palm, then letting it go, searching for coded messages in the tire tracks that crisscrossed the mud road. Morning sunlight rolled out like a carpet over low mountains, and her father stopped in the yard of Solace Fork School.

“You'll like it, Liza.” He grinned at her, an almost-tug on her hair melting her heart. Inside, the smells were oiled floor and chalk.

She was new to this place, but her father was not. Summers spent here with cousins as a boy were his passkey, unlocking lidded eyes. He had returned a doctor, a man “what knew things.” Liza stood as his daughter before the children of Solace Fork School, her dress unpatched, in shoes that only she had worn, the teacher's warm hand on her back. Her hair curled, an alive, rich auburn, not baked to transparency by the sun. Girls' hands twitched, wanting to touch it. Her well-formed body had never hungered, and ten spines straightened to match hers. Eyes widened at her that day and never closed. Forty years later, waist thick, hair faded, and dues paid, her life trailed out behind her like a tattered peacock's tail, yet the folk of Solace Fork still treated her like an exotic stranger.

Only Martin really saw her. That morning he appraised her, while Hodge Goforth blinked curious from the next desk over. Martin's fingers tapered slender as beeswax candles. Dark hair fell over his brow, covering one green eye. The other winked at Liza, long-lashed and shameless, her father standing right there.

At recess, before the girls could draw near enough to claim her, he was at her desk, Hodge shuffling behind. Martin might as well have put his arm around her shoulders.

“Come with us. We've a place to show you.” The mountain had pressed his vowels flat, and “you” was “ye.” She missed that boy's voice, now that only perfect words dropped from Martin's mouth, all polished smooth like rocks from a tumbler.

She walked with him and Hodge down a rough deer path into the woods without a thought, something she would never let her two daughters do today. She heard the creek before she saw it, water burbling, heavy drops plopping from rhododendron leaves. The boys turned off the path. They ducked under limbs and came out into a clearing.

It was a sanctuary. Soft grass the greenest she had ever seen carpeted the aisles. Martin and Hodge had swept it clear of leaves. All around, mature hardwoods grew bent in the shapes of chairs, up, then sideways, then up again, a dozen giant church ladies sitting down. She could just see water through the trees, light brown where it flowed over rocks and almost black at the deep place where the creek branched.

Martin watched her, triumphant. Hodge looked worried, not ready to share this place.

She reached out to touch the closest tree. “How did they grow like this?”

Martin rested his hand next to hers, stroking the bark as if petting a horse. “A storm hit them in nineteen aught two, when they were too big to snap back and too little to come up by the roots. They grew sideways and then back up toward the sun.”

Hodge cleared his throat and spoke for the first time. “It's the onliest hurricane to ever make it this far west. They say it sucked the water out of every creek between here and the coast and spat it out on Spivey's Bald.”

Martin cupped his hands into a stirrup. “Want to climb up?”

She let him help her up onto the tree's broad bench, tucking in her dress. She could smell her own clean scent and Martin's, too, homemade rose soap that lingered in her nostrils. He hopped up beside her. From up there, the grove of trees was an eerie elephant graveyard, a field of bent bones.

“It's so odd,” she said.

Martin's trousered leg touched hers. Sun filtered through the trees, dappling the grass and warming the top of her head. Down below, Hodge shifted from one foot to the other, opening and closing his hands.

A ladybug landed on Liza's knee. Martin reached over and gently brushed it off. “Maybe we'd grow crooked, too, if we got hit in the middle by a storm.”

*Â Â *Â Â *

Liza drove to that place now, reaching her destination in the dark. She pulled a flashlight from under her seat and let the slam of the truck door puncture the cool silence. Solace Fork School stood abandoned, marked for demolition, the children bused to bigger buildings of aluminum and glass. The deer path was still there. She pushed through autumn-dried blackberry thorns to the clearing. The creek that forked wide here was the same creek that ran through the Owenby property. She could hear the water whispering.