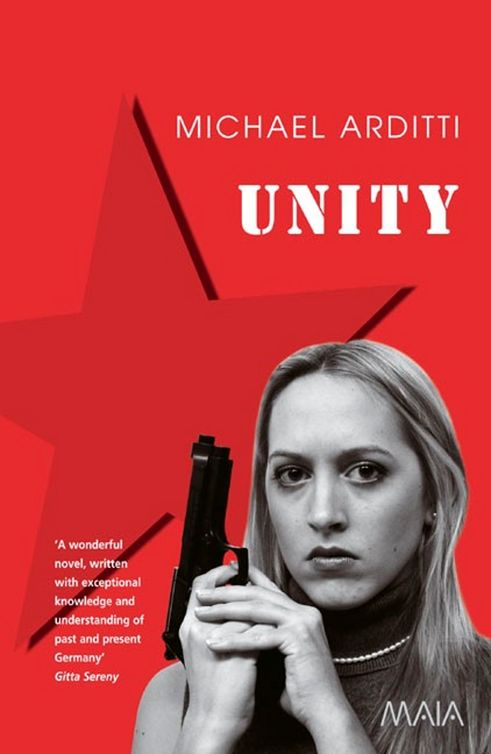

Unity

Authors: Michael Arditti

MICHAEL ARDITTI

For Luke Dent

(21.2.1955–15.4.2001)

‘And have no fellowship with the unfruitful works of darkness, but rather reprove them. For it is a shame even to speak of those things which are done of them in secret.’

St Paul

‘He who fights with monsters might take care lest he thereby becomes a monster. And if you gaze for long into an abyss, the abyss gazes also into you.’

Kierkegaard

‘If you don’t love the character, then you can’t play him.’

Laurence Olivier

‘Whenever I hear the word culture, I reach for my pistol.’

Hermann Göring

Unity

CAST

| | | Unity Mitford | Felicity Benthall |

| | | Diana Guinnesss | Geraldine Mortimer |

| | | Jessica Mitford | Carole Medhurst |

| | | Lord Redesdale | Gerald Mortimer |

| | | Lady Redesdale | Dora Manners |

| | | Sir Oswald Mosley | Liam Finch |

| | | Sir David St Clair Gainer | Hallam Bamforth |

| | | Brian Howard | Luke Dent |

| | | Adolf Hitler | Ralf Heyn / Wolfram Meier |

| | | Joseph Goebbels | Manfred Stückl |

| | | Magda Goebbels | Liesl Martins |

| | | Hermann Göring | Henry Faber |

| | | Emmy Göring | Renate Fischer |

| | | Julius Streicher | Dieter Reiss |

| | | Ernst Hanfstaengl | Helmuth Wissmann |

| | | Heinrich Hoffmann | Conrad Seitz |

| | | Erich Wielderman | Erich Leitner |

| | | Eva Braun | Luise Hermann |

| | | Eva Maria Baum | Hannelore Kessel |

| | | Elderly Jew | Per Lindau |

| | | | |

| | | Director | Wolfram Meier |

| | | Producer | Werner Kempe |

| | | Screenplay | Luke Dent |

| | | | (from his own play) |

| | | Executive Producer | Thomas Bücher |

| | | Director of Photography | Gerhard Korn |

| | | Music | Kurt Stolle |

| | | Production Designer | Heike von Stripp |

| | | Make-up Artist | Beate Pauli |

Filmed on location in England and Germany, and at Bavaria Studios, Munich (August–October 1977)

For a writer to have gone to university with an international terrorist is a mixed blessing. On the one hand, he feels pressure from both his publishers and himself to provide his unique slant on the story, on the other, a reluctance to reopen old wounds. So much nonsense has been printed about Felicity Benthall that I would dearly like to set the record straight. And yet a fear of what my investigations might uncover has so far restrained me. What if a chain of complicity reaches back to the chance remark of a college contemporary’s – or, worse, of mine? What if an old acquaintance reveals Cambridge to have been as fertile a

breeding-ground

of fanaticism in the 1970s as it had been forty years before? I am caught between conflicting abstractions. Commitment to the truth contends with the determination to spare my friends – and, indeed, my whole generation – from further attacks.

The facts of the matter are plain. In October 1977, Felicity Benthall, a twenty-three-year-old English actress, attempted to blow up the diplomatic representatives of most of the United Nations at a service to commemorate the eleven Israeli athletes murdered at the Munich Olympics five years before. She succeeded only in killing herself, her uncle the British Ambassador, his deputy, two secret servicemen and the Polish chargé d’affaires. Immediately after her death, a statement was issued in Beirut by the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine claiming her as a martyr to its cause. Meanwhile, in Stuttgart, the Red Army Faction (otherwise known as the Baader-Meinhof group), the small band of revolutionary Marxists whose campaign of terror over the previous decade had plunged West Germany into its greatest political crisis since the end of the Second World War, also claimed that she was acting on its behalf.

Nowhere was the shock of the atrocity more deeply felt than among those who had known – or who thought that they had known – Felicity best. Try as we might, it was impossible to square the cynic who had drawled that all ideology was a bore with the fanatic who died for a principle that was, in every sense, foreign to her. Like any other observer – but with an added sense of frustration – we were left to wonder whether her behaviour had been driven by idealism or nihilism: whether she had been malevolent or mad. Moreover, by a coincidence which I decline to call an irony, she had been playing the role of Unity Mitford, the English aristocrat whose extremist views led her to fall in love with Hitler. The film, by Germany’s foremost post-war director, Wolfram Meier, was then abandoned. Like Sternberg’s

I Claudius

and Welles’s

Don Quixote,

Meier’s

Unity

has become one of cinema’s most celebrated might-have-beens. The untimely deaths of many of the leading players have contributed to its legendary status, creating the cinematic equivalent of the curse of

Macbeth

.

That was clearly the opinion of the film’s writer, Luke Dent, who, in the immediate aftermath of the attack, declared: ‘I know now that a writer must take full responsibility for his ideas, like a scientist with the H-bomb. There is certain research that is too dangerous to publish. It should be left in the study or the lab.’

1

My own reluctance to engage too closely with Felicity’s story stemmed from a similar unease. But, with the discovery of Geraldine Mortimer’s diaries and Luke’s subsequent – or, indeed,

consequent

– suicide, it became a task that I could no longer shirk. To which end, I have gathered together the varying – and often conflicting – records of events surrounding the film, in the hope of casting light on both Felicity’s actions and the social, political and metaphysical issues that these raise.

i.

Credo

I should say from the start that I have never believed in evil. I take an innocent until proven guilty attitude to the human race. Even in guilt, there are mitigating factors. At prep school, I was taught that ‘evil is good gone wrong’. And, although I soon came to realise that that left much unanswered, the loss of credulity did not lead to a loss of faith. I have been sustained all my life by the figure of Christ and the knowledge that God’s love was embodied in a man – and, by extension, in every man. This, together with my fervent conviction, often held in the face of all the evidence, that people are fundamentally decent led me, first instinctively, and then intellectually, to reject the concept of Original Sin. Later, Marx and Freud, two philosophers who in both appearance and stature came to resemble the prophets they had displaced, added secular authority to my belief that what was commonly called evil was simply the behaviour of people in the grip of social and psychological forces that they could not control.

‘What? Even Hitler?’ is the automatic response of my critics. Hitler is, after all, a byword for evil (and a not inconsiderable presence in the account that follows). ‘Yes, even Hitler,’ is my reply. The nature of the forces that shaped him may be open to dispute – and was, indeed, the subject of several on the set of

Unity

– but that is hardly surprising when it is impossible to reach agreement on something as uncontroversial as his favourite film.

2

I am convinced, however, that such an interpretation is possible (in my amateur way, I made the attempt at Cambridge). Explanation is extenuation. After all, what is the alternative? Are we going to make him such a symbol of evil that he moves beyond the realm of human responsibility? In demonising Hitler, we are employing the same imagery that he did of the Jews.

A comparable danger awaits those who try to draw parallels between Unity and Felicity. I admit that the idea has its

attractions

. They were both young Englishwomen (Unity was twenty when she first met Hitler; Felicity twenty-one when she first met Wolfram Meier), who sprang from a similar upper-class

background

. Both loved to shock: Unity took her pet snake to deb dances and gave the Nazi salute at the British Embassy; Felicity played a record of

Spirit in the Sky

from the belfry of her college chapel and claimed that her family motto was ‘Spit, don’t swallow’. Both were seduced by a cause of which they knew only the trappings. But there the comparisons end. To suggest that history was repeating itself is almost as crass as to suggest that Unity’s spirit had entered Felicity. There is no store of primal evil working itself out down the generations, nor was Felicity the victim of diabolic possession.

Such lurid speculation

3

was much in evidence in the months following Felicity’s death. Talk of the over-identification of actor and role has become a staple of newspaper arts pages, fostered by actors themselves in an attempt to authenticate their performances by reference to their psychic pain. But, unless we are to believe that the profession is made up of intrinsically unstable people – a view which, admittedly, the ensuing pages do little to refute – we would do well to search for our explanations

elsewhere

. Or is every Othello a potential wife-murderer, Faust a necromancer and Dr No a menace to the world?

My resistance to writing about Felicity stemmed from practical as well as psychological causes. I am a novelist, not a journalist or a historian, and yet any attempt to fictionalise her story would be bound to provoke accusations that, far from trying to establish the

truth, I had something to hide. Added to which, the more I reflected on events, the more I grew convinced that it was in the sheer incompatibility of the different interpretations that the truth lay. This distinction would be lost if I tried to tell the story in my own voice. Moreover, I myself was present only at the beginning of

Unity

’s life and, although I was the recipient of a first-hand account, my experience of the filming was one of distance, which I cannot believe is of interest to anyone other than myself.

Gradually, my doubts were whittled away. After completing my third novel, I resolved to take a break from fiction. Instead of giving interviews, I would conduct them. By tracking down the remaining participants, I would make up for my own absence from the set. I am grateful to Thomas Bücher, Liesl Martins, Manfred Stückl and Carole Medhurst for submitting so graciously to my questions. My thanks are due to the trustees of the British Film Institute and to the executors of the late Lady Mortimer for allowing me to reproduce Geraldine Mortimer’s Munich diaries.

4

It was Lady Mortimer’s bequest of her husband’s and

stepdaughter

’s papers to the BFI that sparked off this inquiry, and I am obliged to my friend, Ralph Waller, for alerting me to the material. I am likewise indebted to Renate Fischer for allowing me to quote from her monograph on Wolfram Meier, which, for reasons that will be touched on later, has yet to find a publisher in her native land.

My literary priorities have changed to a greater degree than my writing practice. I may not have invented the narrative but I am still shaping it, not least in the arrangement of the various contributions. There is no reason for my placing Luke Dent’s letters before Geraldine Mortimer’s diary other than my desire to give them pre-eminence: to make them the template for all that

follows. They were my own introduction to the story. Those who prefer to read the book in the order in which it came into being should read Geraldine Mortimer’s account first. Those who prefer to read it in chronological order should read Renate Fischer’s. Before reading any of the others, however, I hope that they will read mine.

ii.

Cambridge

Although it later became a cause of contention and now seems a dubious honour, I still claim credit for conceiving the

Unity

play. Its genesis was at Cambridge, which Felicity, Luke and I all attended between 1973 and 1976. It was a golden age. When I was asked at a recent reading to define the purpose of a university education, my instant reply was ‘the pursuit of knowledge in the company of friends’. The students looked blank. Their overriding purpose was the pursuit of qualifications with a view to a job. There could be no clearer indication of the passage of time. Twenty-five years ago, we had invested all our efforts in college entrance … it would not be too fanciful to see our passion for the 1920s as a reflection of our own sense of miraculous survival and licence to have fun. In any case, we gave no thought to the future. We had passed the test (which was something far subtler than the examination). We waltzed through the portals of privilege with our destinies assured.

After a first term still imbued with the ethos of school, I focused more on friends than on knowledge. The two who came rapidly to dominate my life – indeed, to define it – were Felicity and Luke. We met at an audition and our subsequent relationship was, in varying measure, tinged with the theatrical. I was the only one to be cast, which immediately set me apart. The real distinction, however, came later that evening when Felicity stayed in Luke’s room. ‘Placing Girton so far out of town, what do they expect?’ she asked,

in defiance of the college’s founders who believed that distance would be a safeguard of virtue. I met them for lunch the next day. I had not yet alerted them to my sexual preferences (I had not yet articulated them to myself), but Felicity’s casual assumption conveyed instant approval, while Luke’s grammar school

background

left him with no residue of guilt for which to atone.

Such a tight-knit trio inevitably gave rise to gossip, but our

relationship

was far more conventional than it appeared. Felicity slept with Luke and I slept with no one. When Felicity joked that I should be called a homosexless, I laughed because I thought it was funny. At least I think that I did. Felicity and I slept together once – with Luke’s bruised blessing – but it was more of a biology lesson than a romantic tryst. At the time, my heart was still set on acting. Stanislavski was king and Felicity insisted that I required a heterosexual experience to store in my emotional memory.

Needless

to say, I never slept with Luke. I sunbathed with him in Naxos, showered with him in Scotland and rubbed make-up on his back in ancient Rome. But I never slept with him. I am, however, the one who wrote the inscription on his grave.

The attractions of the arrangement for Felicity and myself were clear. I was able to cast my adulthood in the mould of my childhood, while she was able to swathe herself in an aura of mystery as thick as the fug produced by her trademark

Black Russian

cigarettes

. Too fastidious for orgies and too indolent to sleep around, she looked to us to save her from the bourgeois (the dirtiest word in her dictionary). We brought a touch of Truffaut into a world of E. M. Forster, even if the triangle were less elegantly balanced than that of

Jules et Jim

. Above all, she feared commitment. Just as her chronic procrastination derived less from inefficiency than from a sense that something more exciting must be about to happen elsewhere, so she loathed being tied down. A third person provided the prospect of release even if, in my case, it was more symbolic than real.

For Luke, the attractions were both less obvious and the subject of constant speculation on my part, as I attempted to reassure myself of his commitment to the trio. I was convinced – wrongly, as it turned out – that any rupture would be brought about by him. My self-lacerating conclusion was that Luke was a liberal who saw me as a potential cause. He pictured himself defending me from the repercussions of a scandal, waiving private distaste for the sake of a general principle. At times of greater self-

confidence

, I cast myself as his soul-mate … the friend for whom he used to yearn when he was growing up in Africa and forbidden to mix with the local boys: the friend for whom he used to yearn when he returned to England and found that all the significant allegiances had already been formed. His primary motivation, however, was the desire to please Felicity, his first proper

girlfriend

, to whose personal volatility was added all the enigma of her sex.